Scientists identify a new gene that can prevent aging

Scientists may be one step closer to unraveling the secrets of anti-aging.

They have discovered that stimulating a gene we all possess can slow the rate at which our cells wear out.

The Chinese academics stumbled upon the discovery while studying the DNA of fruit flies, when they discovered that a single insect gene determined whether they died young.

They ran the gene through a human database and found a 93 percent match to a human gene known as DIMT1.

Chinese scientists have identified a new gene that could extend human lifespan by 30 percent

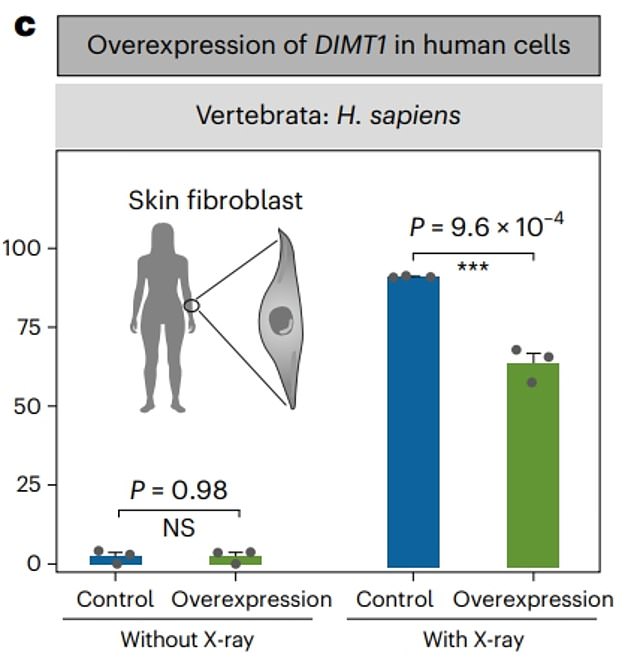

In laboratory studies, they exposed human cells to radiation to cause damage somewhat similar to the age-related breakdown that occurs in humans.

They discovered that the cells with an increased DIMT1 gene ‘aged’ 65 percent slower than the unchanged cells.

Now the team hopes the findings will stimulate research into ways we can activate this gene in people with modern drugs.

The research was published in the journal Nature aging.

Both the human and insect genes change the shape and structure of their mitochondria, which play a role in balancing oxidative stress that drives the aging process.

Mitochondria are responsible for producing energy (called ATP) that the cell needs to function, which is similar to power plants in our bodies that provide the energy that cells need to function.

If our cells don’t get the energy they need, tissues or body organs don’t work properly – and the aging process begins.

To find these anti-aging genes, the team looked at 1,283 DNA segments in insects, finding an uncharacterized CG11837 gene that regulates their lifespan.

When researchers increased the gene’s activity, the fruit flies lived up to 59 percent longer.

Using the AlphaFold2 database, which an AI program predicts protein structures, the team looked for similar genes in humans.

They found that the structure of CG11837 was similar to the human gene DIMT1.

The team conducted in vitro studies using human cells, enhancing them to produce more DIMT1. The modified cells grew 2.4 percent more than the unmodified cells. The two groups were subjected to an X-ray, which showed improved cells that were 65 percent less old

The team conducted in vitro studies using human cells from an adult male, enhancing them to produce more cells DIMT1 for three days.

The modified cells grew at the same rate as the unmodified cells, but when the team exposed both groups to X-rays, which damaged cells, they noticed a difference.

The The improved group was 65 percent younger and grew 24 percent more than those in the control group.

The team believes their research is a step toward creating new gene therapies, which are designed to alter a person’s gene to treat or cure disease.

And researchers found that the treatment reversed aging in mice.

Mice given an experimental gene therapy lived 109 percent longer after treatment than mice given a placebo.

This gene therapy is not yet available for humans, but experts say it could be within five years.