Scientists drop extinction bombshell, claim freak event killed the last woolly mammoths

Scientists conducting a new genomic study claim that the last woolly mammoths on Earth were wiped out by an extreme storm or plague. If the species had not gone extinct, they might still be around today.

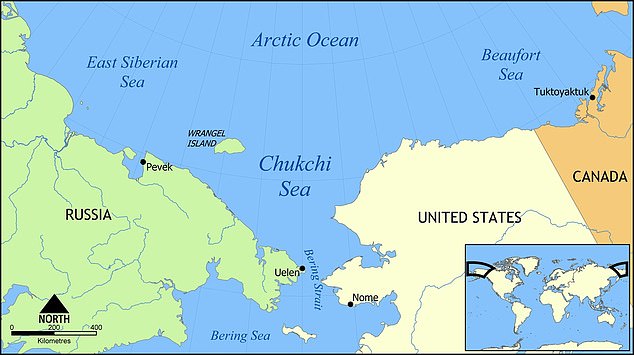

These gigantic Ice Age beasts crossed the then tundras of North America, Europe and Asia up to 300,000 years ago. They later became extinct, about 4,000 years ago, on an isolated island off the coast of Siberia in the Arctic Ocean.

The latest analysis shows that a few hundred woolly mammoths were confined to tiny Wrangel Island for about 6,000 years, but scientists say they did not die from inbreeding. The guard reported.

The long-held theory was that woolly mammoths eventually induced enough damaging genetic mutations to create a ‘genomic meltdown.

“We can now confidently reject the idea that the population was simply too small and that they were genetically doomed to extinction,” says evolutionary geneticist Love Dalén of the Centre for Paleogenetics, a collaboration between Stockholm University and the Swedish Museum of History.

Woolly mammoths roamed the Ice Age tundras of North America, Europe and Asia up to 300,000 years ago. They later became extinct, about 4,000 years ago, on an isolated island off the coast of Siberia in the Arctic Ocean.

Scientists now believe mammoths were killed by a random event – such as bird flu or a storm – and not by inbreeding, as previously thought

“That means it was probably just a random event that made them extinct.” If that random event hadn’t happened, we would still have mammoths today,” he continued.

Dalén and his colleagues analyzed the genomes of 21 mammoth specimens found on Wrangel Island and the Siberian mainland, representing an existence of 50,000 years.

In the photo: Professor Love Dalén

They found that the prehistoric creatures were in a “severe bottleneck situation” when they became stranded on Wrangel Island, due to rising sea levels caused by global warming.

At one point during the Holocene (11,500 years ago to present), the total population was eight or less.

“These findings suggest that Wrangel Island may have been settled by a single herd of woolly mammoths,” the study said.

According to the study authors, you would normally expect a species to undergo “accelerated genomic decline,” but that’s not what happened.

“The population recovered rapidly after the bottleneck and remained stable thereafter. More precisely, we find evidence that the recovered population was large enough, or perhaps changed its behavior, to avoid inbreeding with close relatives … during 6,000 years of island isolation,” the study said.

So if they were ultimately able to avoid inbreeding, what killed them all?

Wrangel Island, where woolly mammoths made their last stand as a species, lies just above the northeastern tip of Russia

The tusk of an extinct woolly mammoth. It is about 4,000 years old and was found on Wrangel Island

It is not clear and will probably never be completely clear, but Dalén thinks that something like bird flu could have killed the species.

‘Perhaps the mammoths would have been vulnerable to this, given the reduced diversity we identified in the genes of the immune system. Alternatively, something like a tundra fire, a volcanic ash layer or a very bad weather season could have caused a very bad growing year for the plants at Wrangel.”

“Given the small size of the population, it was vulnerable to this kind of random event,” Dalén said, adding, “It seems to me that the mammoths were just unlucky.”

The paper’s lead author, Marianne Dehasque of Uppsala University, told the Guardian that this new story about how mammoths became extinct holds a lesson for today’s world, as biodiversity continues to decline every year.

The World Wildlife Fund’s 2022 Living Planet Report found that wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69 percent over the past 50 years.

“Mammoths are an excellent tool for understanding the ongoing biodiversity crisis and what happens from a genetic perspective when a species reaches a population bottleneck, because they reflect the fate of many current populations,” Dehasque said.