Scientists discover what caused the collapse of the Roman Empire 1,500 years ago

Scientists have discovered an unlikely event that led to the collapse of the Eastern Roman Empire 1,500 years ago.

They discovered that the Romans had misjudged their Persian opponents, which caused their downward spiral, leaving them weak and Islam rising in a way that essentially wiped out the once mighty civilization.

The two groups were at war for control of territories from 54 BC to 628, but the Persians took over Roman trade routes that were crucial to their victory.

Without access to trade, the economy quickly collapsed, forcing people in the Roman Empire to flee to other regions such as Constantinople, the researchers said.

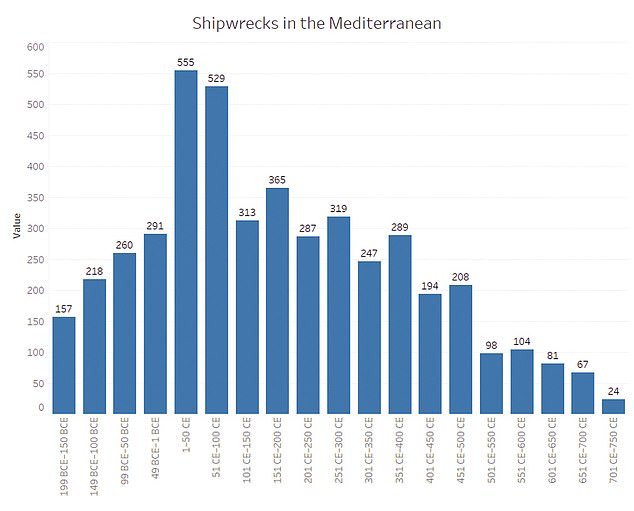

The team analyzed shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea from multiple locations, such as Marseille, Naples, Carthage, eastern Spain and Alexandria, to better understand what caused the fall.

They identified a timeline for when Roman ships, which at their peak numbered in the hundreds along the coast, began to disappear, dwindling to just dozens by the second half of the 7th century.

Roman goods from the same period were also analyzed tens of thousands of locations across numerous regions including Israel, Tunisia, Jordan, Cyprus, Turkey, Egypt and Greece, indicating the group was still in the middle of trading.

Researchers said that in the second half of the 6th century AD, there was not a decline, but an increase in prosperity and demography.

The information “led us to the conclusion that the Eastern Roman Empire began to decline… after a (trade disruption) and military failures,” authors Lev Cosijns of the University of Oxford and Haggai Olshanetsky of the University of Warsaw to DailyMail.com.

Researchers have discovered that the collapse of the Roman Empire was caused by the Roman-Persian War, which cut off trade routes and left them weak.

Previous research had suggested that a plague decimated the Roman Empire in 543 AD or that there was a climate shift that peaked in the mid-6th century.

But the new study found that civilization was at the height of its power, economic output and population.

“So it seems that 536 CE was not the worst year to be alive,” Cosijns said. ‘At least, not for most people who lived at that time.

‘It was a terrible period for people living in Scandinavia, but for people living in the Eastern Roman Empire the consequences were limited and life continued as normal.’

The researchers began their investigation by dating pottery discovered at archaeological sites.

They discovered more than 16,000 pieces of pottery discovered in Nessana, a town in Israel’s southwestern Negev Desert, close to the Egyptian border.

The pottery was traded by the Roman Empire in the late 6th and early 7th centuries, confirming that the civilization was still flourishing.

The team found a ‘strong increase’ in the total number of pottery sherds dating from after 550 AD, which they said indicated ‘increasing the region’s industrial capacity and prosperity.’

The researchers looked at shipwreck records that showed trade was constant until the routes were closed in the 6th century

“This is especially noticeable at Nessana, which dates from 550 to 700 AD, where a total of 16,148 sherds were found, a greater number than all other areas and contexts from all sites combined,” they shared in the study.

The team then used Harvard University’s shipwreck database and the Oxford Roman Economy Project (OXREP) database to identify a timeline for the heyday of Roman shipping in the Mediterranean.

These databases collected data on ancient shipwrecks, including their dates, name of the site/shipwreck, GPS location, and cargo.

“The use of this type of data implements a method that has recently been applied in several studies,” researcher wrote in the study published in the scientific journal magazine Klio.

‘This method assumes that the number of shipwrecks has statistical significance, and greater amounts of maritime traffic are reflected in higher numbers of shipwrecks in certain periods.’

The researchers said that during the 2nd century AD, the number of Roman shipwrecks remained consistent, with between 200 and 300 occurring every 50 years.

“And then, at the very end of the 5th century, there is a sharp decline of almost fifty percent in the number of shipwrecks,” the team said.

‘The reason for such a severe reduction was most likely due to the fall of the Western Roman Empire at the end of the 5th century.

‘The fall of the West also symbolized the decline of the city of Rome and other Western trading cities and their hinterlands, and the subsequent population decline.’

The records also showed that the number of ships had fallen to just 67 in the second half of the 7th century, meaning their trade routes had been cut off.

“This decline was most likely a result of the Persian War and the Islamic conquest shortly afterwards, which deprived Constantinople of most of the areas previously under the rule of the Eastern Roman Empire,” the researchers said.

The Romans fought the Persians to gain control of areas that could protect their borders and provide valuable trade routes

The Roman and Persian Empires fought to control territories to expand their influence throughout Armenia, Mesopotamia, and northern Syria.

These areas were strategically important because they provided greater border protection and access to vital trade routes.

The Roman Empire won the war under the leadership of Emperor Heraclius, who launched a counterattack deep into Persian territory, overwhelming the army and forcing them into a decisive battle near the ruins of Nineveh.

But the disrupted trade route slowly weakened the Roman Empire, leading to their demise.

The researchers say their findings go against the grain of others who downplay the current climate crisis by linking the mini-ice age that occurred in the 6th century to the fall of the Roman Empire, claiming this has always happened and is therefore nothing to worry about. to worry about. .

“We think that looking for climate change and the plague as the cause of every major change in history is problematic,” Olshanetsky and Cosijns said.

“This approach could be especially damaging to the current climate change debate if it claims that climate change has historically caused catastrophic disruptions to society, in cases where there have been no or limited impacts,” they continued.

“Such claims may inadvertently support arguments that because climate change has always occurred, current human-induced climate change is not a serious problem.”