Scientists discover a ‘smiley’ on Mars — and it could contain signs of life

Astronomers have discovered a feature on Mars that looks like a smiley face. It could be more than just a planetary oddity.

Researchers believe there may be traces of past life on the Red Planet.

This grinning formation consists of a few crater eyes and rings of ancient salt layers.

These deposits are the remains of an ancient body of water that dried up long ago, leaving emoji-like remains that are only visible when viewed with an infrared camera.

The European Space Agency, which took the photo, said: “These deposits, remnants of ancient water bodies, could indicate habitable zones from billions of years ago.”

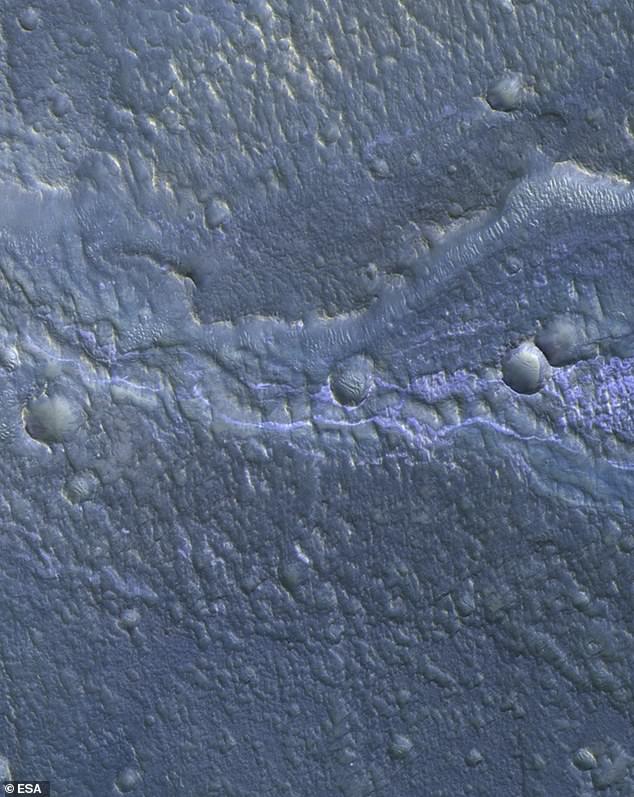

The European Space Agency ESA captured this image of a smiley-face-shaped salt layer on Mars, which may contain evidence of ancient alien life on the Red Planet

Scientists aren’t sure how big the smiley is, but it’s one of 965 other salt layers recently cataloged on the Martian surface. The salt layers range in size from 300 to 3,000 meters wide.

Salt deposits are accumulations of salt—or chloride—found on a planet’s surface. On Mars, they are the remains of ancient bodies of water that dried up when the planet underwent a major climate shift eons ago.

According to the ESA, the last pools of liquid water on Mars may have been a haven for microbial life before they disappeared.

These pools were probably extremely salty, which may have preserved the remains of microbes that once lived there, in deposits like this smiley face.

The ESA created this image using its ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, which has been measuring levels of methane and other gases in the Martian atmosphere since 2016 to give scientists insight into possible biological or geological activity on the Red Planet.

Normally, salt layers on the surface of Mars are invisible.

But thanks to the spacecraft’s infrared cameras, we can see them glow pink or violet, revealing the smiling face.

The photo was published as part of an investigation in the journal Scientific data.

These salt layers are normally invisible, but thanks to infrared cameras on ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, we can see them glow pink or violet.

When Mars’ liquid water disappeared, the last salty pools could still harbor microbial life, and their remains could be preserved in the resulting salt layers.

The research team, led by scientists from the University of Bern in Sweden, used images taken by the orbiter to compile the most comprehensive catalogue of chloride salt deposits on Mars to date.

The new catalog contains data from nearly 1,000 different deposits spread across the Earth’s surface.

These deposits paint a picture of ancient Mars that is very different from the red desert planet we know today. Billions of years ago, Mars contained bodies of liquid water.

“In the distant past, water formed beautiful landforms such as riverbeds, channels and deltas on the Red Planet,” planetary scientist and lead author of the study Valentin Bickel said in an ESA report proposition.

However, studies suggest that these bodies of water dried up between three and two billion years ago due to severe climate change.

This extreme climate change was likely caused by the loss of Mars’ magnetic field, allowing the solar wind to erode the atmosphere and liquid water to freeze, evaporate or become trapped on the planet’s surface.

Salt layers are one of the few evidences we have of ancient water bodies on Mars.

Moreover, studying it would According to the study, the samples reveal clues to ancient microbial life that once lived in the planet’s liquid water.

“The new data have important implications for our understanding of the distribution of water on early Mars, as well as for past climate and habitability,” Bickel said.

While there is no conclusive evidence of past or present life on Mars, this study adds to a growing body of research reviving the search for microbes on the Red Planet.