Scientists discover a new penguin colony from space

>

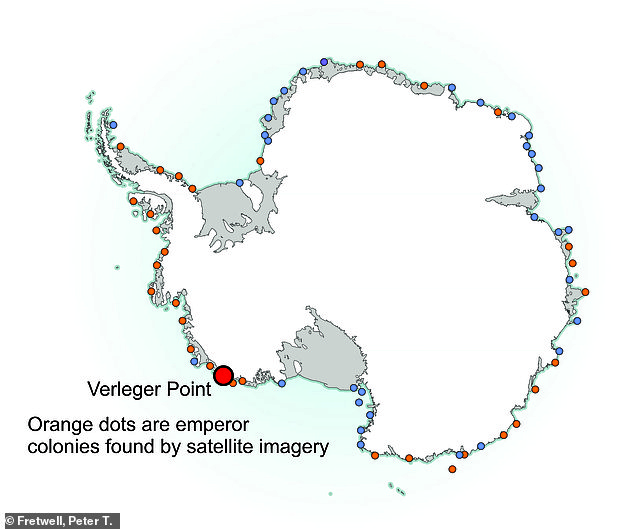

There are more than 60 known emperor penguin colonies living on Antarctica’s coastline — but more than half would have remained undiscovered if they hadn’t been spotted from space.

Satellite imagery has helped detect 33 of the 66 groups by tracking the birds’ poo, or guano, which is brown in colour and easier to identify when it stains large patches of sea-ice.

Among the 66 is a new colony of around 500 penguins which has just been discovered at Verleger Point, West Antarctica.

It is a welcome development, given that the species is likely to come under severe threat as the frozen continent continues to warm.

Good spot: Satellite imagery has helped to identify a new colony of around 500 emperor penguins at Verleger Point, West Antarctica, by tracking the birds’ poo, or guano (pictured)

It is a welcome development given that the species is likely to come under severe threat as the frozen continent warms

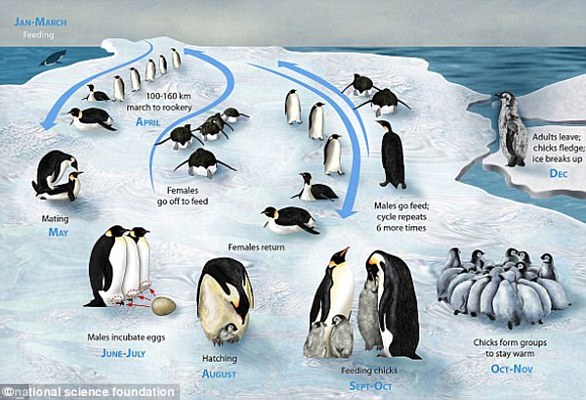

Emperor penguins are known to be vulnerable to loss of sea ice, their favoured breeding habitat, and if this continues to diminish then the animals’ numbers will suffer badly.

Current climate models project that 80 per cent of colonies will be ‘quasi-extinct’ by the end of the century.

This is when a population may be doomed to extinction even if there are still individuals alive.

Even under the best-case scenario, with a global temperature increase of 2.7°F (1.5°C), experts say the emperor penguin population is expected to decrease by at least 31 per cent over the next three generations.

The British Antarctic Survey’s Dr Peter Fretwell, who studies wildlife from space and is the lead author of the research into the uncovering of this new colony, said: ‘This is an exciting discovery.

‘The new satellite images of Antarctica’s coastline have enabled us to find many new colonies.

‘And whilst this is good news, like many of the recently discovered sites, this colony is small and in a region badly affected by recent sea ice loss.’

Researchers studied images from the European Commission’s Sentinel 2 (pictured), one of the Earth observation satellites that makes up the Copernicus Programme, to confirm the finding

Under threat: Emperor penguins are known to be vulnerable to loss of sea ice, their favoured breeding habitat, and if this continues to diminish then the animals’ numbers will suffer badly

For the last 15 years, British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists have been looking for new penguin colonies by searching satellite imagery for their guano stains on the ice.

Emperor penguins need sea ice to breed and are located in areas that are very difficult to study because they are remote and often inaccessible and can experience temperatures as low as −76°F (−60°C).

Dr Fretwell and his team studied images from the European Commission’s Sentinel 2, one of the Earth observation satellites that makes up the Copernicus Programme.

These were then compared to and confirmed by high resolution images from the MAXAR WorldView3 satellite.

Previous discoveries of emperor penguin colonies show gaps between them, leading scientists to suspect that groups like to keep at least 60 miles (100km) between themselves.

Satellite imagery has helped detect 33 of the 66 groups by tracking the birds’ poo, or guano, which is brown in colour and easier to identify when it stains large patches of sea-ice

Warning: Current climate models project that 80 per cent of emperor penguin colonies will be ‘quasi-extinct’ by the end of the century

Although it is impossible to count individual penguins from orbit, experts from the BAS can estimate numbers in colonies from the size of the birds’ huddles, which is where they got the figure of 500 from in the new discovery.

In 2020, BAS researchers once again used satellite mapping imagery to establish that Antarctica was home to 20 per cent more penguin colonies than previously thought.

They spotted 11 new emperor penguin colonies, three of which were previously identified but never confirmed.

At the time it was estimated the continent had between 265,500 and 278,500 breeding pairs.

However, the researchers warned that most of the newly-found colonies were situated at the edges of the emperors’ breeding range, in locations likely to be lost as the climate warms.