Scientists blame a new weather phenomenon dubbed ‘hydroclimate WHIPLASH’ for California’s devastating wildfires – and predict similar events as global warming continues

With the LA wildfire on track to become Southern California’s most destructive fire ever, a timely new study identifies the cause.

Scientists from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) discovered this a global pattern of what they call ‘hydroclimate whiplash’: rapid swings between intensely wet and dangerously dry weather.

After years of severe drought, dozens of “atmospheric rivers” — long, narrow bands of water vapor in the atmosphere — flooded California with record-breaking rain in the winter of 2022-2023, scientists say.

This buried mountain towns under snow, flooded valleys with rain and snowmelt, and caused hundreds of landslides.

After a second wet winter in Southern California in 2023-2024, last year brought a record hot summer and now a record dry start to the 2025 rainy season, along with ‘thorn-dry’ vegetation that has burned off in a series of episodes since. damaging forest fires.

“Los Angeles is on fire, and accelerating hydroclimate whiplash is the most important climate link,” the experts say.

The UCLA team’s study is being published amid LA’s devastating wildfires, which are reportedly caused by overgrown vegetation, dry conditions and unusual winds.

On the morning of January 7, severe drought conditions and winds of up to 100 miles per hour sparked wildfires in the affluent LA suburb of Palisades. Since then, the infernos have killed at least five people, destroyed thousands of homes and forced more than 130,000 residents to evacuate.

‘Hydroclimate whiplash’ is defined as rapid swings between intensely wet and dangerously dry weather. This map shows whiplash events from 2016 to 2023. Shade determination determining the onset, duration and extent of drought conditions

The researchers cite recent weather events in California, including a series of damaging wildfires to start the year. Pictured: The Palisades Fire in Pacific Palisades, California, on January 8, 2025

From storms to floods, droughts and wildfires, intense weather is on the rise worldwide.

This study now warns that these extreme events are linked, with one leading to the other in a jerky ‘whiplash’ fashion.

Climate change is the trigger for weather whiplash, according to the experts – who predict further big increases as global warming continues.

The researchers cite multiple whiplash events between 2016 and 2023, including the South Asian floods of 2022 and fatal bushfires in Australia five years ago.

They also point to recent turbulent weather events in California, including the wildfires now raging through Los Angeles, razing the homes of Hollywood stars.

“Increasing hydroclimate whiplash may prove to be one of the more universal global changes on a warming Earth,” said lead study author Dr. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA.

‘The evidence shows that hydroclimate whiplash has already increased due to global warming, and that further warming will cause even greater increases.’

The team points to ‘anthropogenic’ (human-induced) climate change as the cause of increasing whiplash – including factors such as livestock farming and burning fossil fuels for energy.

Lebron Jones (center) wipes his eyes as he looks at his burned home during the Eaton fire in the Altadena area of Los Angeles County, California on January 8, 2025

January 8: Fires broke out in the northern part of Easton in the evening. The fire has now killed five people and destroyed more than a thousand homes

The researchers cite multiple whiplash events between 2016 and 2023, including the fatal bushfires in Australia five years ago. Pictured: Fire on the outskirts of Bilpin town on December 19, 2019 in Sydney, Australia

Because warmer air can hold more water, climate change is causing heavier rainfall and extreme flooding, leading to landslides on supersaturated hillsides.

But this extra moisture also increases the growth of flammable grass in the months leading up to wildfire season, which usually occurs between June and October.

Extreme drought and heat then dry out the plants, making them more susceptible to fire.

A lightning strike or a man-made spark (such as a campfire or a lit cigarette) are common causes of wildfires, but it is often the dryness of plants that determines how much a wildfire spreads.

For the study, the scientists reviewed previously published scientific papers to identify rapid swings between intensely wet and dangerously dry weather.

Dr. Swain and his colleagues reviewed hundreds of previous articles for the review, overlaying their own analysis on top of them.

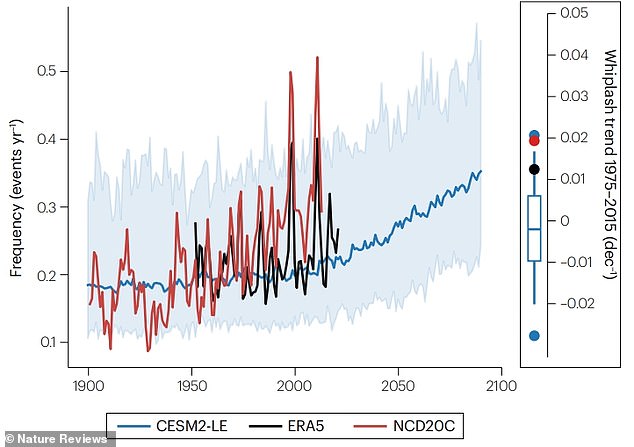

They found that hydroclimate whiplash has increased globally by 31 percent to 66 percent since the mid-20th century – even more than climate models suggest should have happened.

A further increase in the number of whiplash events is expected depending on how much the planet warms. But the researchers predict an increase of 113 percent over land areas with a warming of 3°C (relative to the reference period 1940-1980).

Several climate models, including the EU’s ERA5 model, suggest that whiplash events will increase until the end of this century

People gather at a bridge damaged by the flood on the Raghu Ganga River in Myagdi, Nepal, July 11, 2020

This photo taken on July 8, 2020 shows debris at the site of a landslide in Huangmei County, Huanggang City, Central Hubei Province, China

Hydroclimate whiplash is expected to increase most in North Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Northern Eurasia, the tropical Pacific and the tropical Atlantic, but most other regions will also feel the shift.

The same climate models predict that whiplash will more than double if global temperatures rise 3°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement – an international agreement to control and limit climate change signed in 2015 – aims to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C.

A major cause of whiplash is the ‘expanding atmospheric sponge’: the atmosphere’s growing ability to evaporate, absorb and release seven percent more water for every degree Celsius the planet warms, the team said.

‘The problem is that the sponge is growing exponentially, like compound interest at a bank – the rate of expansion increases with every fraction of a degree of warming,’ said Dr Swain.

In their article, published today in Nature reviewsThe team predicts that “historic increases in hydroclimate volatility will continue with continued anthropogenic warming.”

“The less warming there is, the less increase in hydroclimate whiplash we will see,” Dr Swain added.

‘So anything that would reduce warming due to climate change will directly slow or reduce the increase in whiplash.

‘Yet we are still currently on track to experience global warming of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius this century.

‘So a substantial further increase in whiplash is likely in our future, and we really need to take this into account in risk assessments and adaptation activities.’