Scientist challenges ‘out of Africa’ theory with new origins for modern humans

An evolutionary biologist has challenged the long-standing theory that suggests the first humans emerged from Africa.

Dr. Huan Shi of China argued that evolution began in East Asia, where fossils have been found that predate the African timeline.

Evidence of genetic diversity is at the heart of his ‘out of East Asia’ theory, based on a concept called ‘maximum genetic diversity’ (MGD), which states that complex species are likely to have less genetic diversity.

Dr. Huang said that because East Asian populations have the least genetic diversity, they are likely the true ancestors.

Ancient Europeans also turned out to be much closer to East Asians, he argued, in both their paternal and maternal genetic makeup.

By this logic, the archaeological finds of early humans with the most genetic similarities to each other and to today’s broader, widespread human race are the most likely candidates for the origin of the species, Dr. Huang has argued.

If the “out of Africa” model were correct, the now recently retired biologist would have noted that the DNA of 45,000-year-old European specimens would better match ancient African DNA.

“Ancient DNA (aDNA) from the oldest modern humans found in Europe, which was published this week,” Dr. Huang said in late December, “again showed more similarity to Asians than to Africans.”

“From Africa,” he boasted, “has been repeatedly refuted by aDNA!”

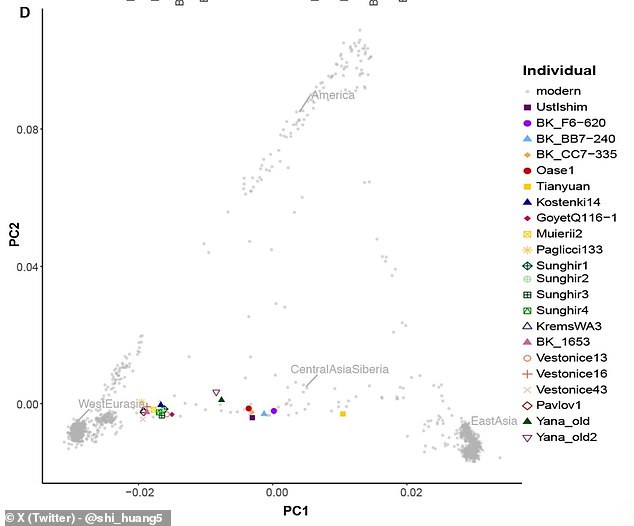

Dr. Huang Shi’s ‘from East Asia’ theory – supported by analyzes of ancient DNA – posits that humans first emerged in Asia, where fossils predating the African timeline have also challenged the established theory. Above: a map of sites containing the oldest human remains

A 2017 analysis shows that Dali’s skull (pictured) shares many features with modern humans – a finding that Dr. Supports Huang’s ‘from East Asia’ hypothesis

The reason his MGD theory is correct, he said, is that more complex organisms like humans require many more parts of their DNA to work together, meaning there is less room for mutations that behave like genetic “improvisations” to occur. to survive.

“A simple thought experiment can explain this,” Dr. Huang wrote in an article published last November in the Chinese-language journal Prehistoric archaeology.

‘You can create three different groups of organisms – yeast, fish and humans – using the same gene sequence, and then let these three organisms diverge for a long time, or about 500 million years.

“A gene in yeast will change a lot, like 50 percent, and the corresponding gene in fish will also change more but less than yeast, like 30 percent,” he continued, “(but) the corresponding gene in humans will change.” very little, for example 1 percent.’

This documented trend in the history of several species suggests that dramatic mutations in more complex creatures are less likely to survive the long term of evolution.

Dr. Huang, who before his retirement was a professor of epigenetics at the Center for Medical Genetics at Central South University in Hunan, has struggled to get mainstream academia to accept his theory. But scholars are increasingly dismissing it.

“The MGD hypothesis is an innovative but indeed controversial theory,” says Stanford-trained anthropology researcher German Dziebel.

Dziebel pointed out that there is broad consensus that older European human DNA samples are less diverse than more recent samples.

The MGD theory and therefore the ‘out of East Asia’ theory it supports ‘has potential’, according to Dziebel, ‘and needs to be further developed.’

Above, a dramatized portrait of a primordial caveman wearing animal skin and hunting with a stone-tipped spear

“Ancient DNA from the oldest modern humans found in Europe,” Dr. Huang said this month, “showed more similarity to Asians than to Africans.” Above, a map of genetic differences showing how close the DNA of ancient Europeans and Asia has proven to be (bottom region)

Evidence from other academic disciplines, including linguistics and kinship anthropology, also appears to support the theory, Dr. Huang said.

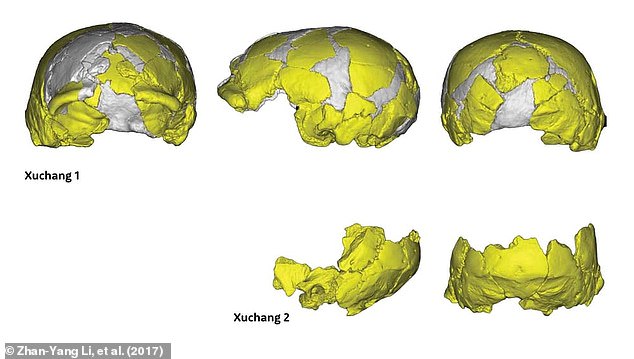

This included analysis of the remarkably complete ‘Dali skull’, discovered in 1978 in China’s Dali Province, Shaanxi Province.

This 260,000-year-old skull, excavated with its face and braincase still intact, was examined in 2017 by experts from Texas A&M University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who found it shares many features with modern humans.

The ‘Dali skull’ turned out to be remarkably similar to what was once the earliest known fossil of Homo sapiens, found 10,000 kilometers away in Morocco.

Rather than choosing a side in the “from Africa” versus “from East Asia” debate, these researchers sought to take a compromise route.

Homo erectus (skull shown on the left, reconstruction on the right) is thought to have been an important early human ancestor in our own evolution. The Chinese ‘Dali’ skull was originally thought to be from Homo erectus, but 2017 analysis shows it is remarkably similar to Homo sapiens

“I think gene flow could have been multidirectional, so some of the traits we see in Europe or Africa could have originated in Asia,” Texas A&M professor Sheela told me. New scientist.

But to set the context, the dominant ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis of human origins has long maintained that modern humans only first appeared in southern Africa some 50,000 years ago – hundreds of years after ‘Dali’ Homo sapien lived and died.

“Out-of-Africa advocates are effectively silent at the moment because they have made virtually no progress in the past decade,” Dr. Huang said. the South China Morning Post.

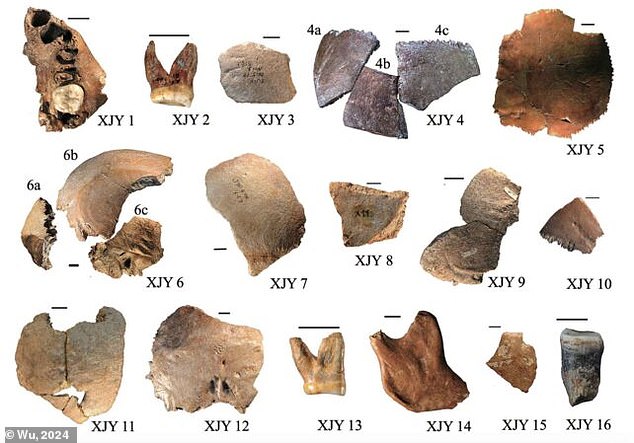

Scientists have also found the skull of an ancient human in China – homo julurensis – who is believed to have had the largest brain of any known hominin, based on the abnormal size of its skull (above as a digital representation). This clever old person can also support Dr. Huang’s theory

Comparing skull fragments found in China (above), experts estimate that Homo julurensis would have had a skull volume of 1700 ml – much larger than any other known hominin.

This growing body of supporting evidence is cause for optimism for Dr. Huang and his fellow proponents of the East Asian theory.

In the eight years since Dr. Huang and his team first presented their “out of East Asia” theory at an international academic conference in 2016, he has been unable to find an academic journal outside China willing to publish the theory.

“We tried to submit the article to many journals but were rejected, so we gave up,” Huang said.

“Any intellectual who wants to overthrow public opinion will face the same difficulties,” he said. “But it’s fine as long as what you’re promoting is true and you don’t care how long it takes (to be accepted).”