Routine practice of just monitoring abnormal cells spotted in smear tests ‘may quadruple risk of cervical cancer’

Monitoring rather than removing abnormal cells can quadruple the risk of cervical cancer, a study shows.

In one of the first studies into longer-term risks, researchers found that choosing regular checkups instead of removal carries an increased risk.

Experts believe this may be due to the previously dormant human papillomavirus (HPV) being reactivated as a person ages or their immune system is weakened.

They said the findings are important for future management and guidance provided to patients in making treatment choices after screening results.

In Britain, women aged between 25 and 64 are invited for cervical cancer screening to check for cervical cancer.

NHS cervical screening data shows that uptake was the highest that year (75.7 percent). It has since fallen to 68.7 percent in 2023

In Britain, women aged 25 to 64 are invited for cervical cancer screening to check for cervical cancer (Stock Image)

It picks up abnormal cells on the cervix, known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), which are assessed based on the risk they pose of developing into cancer.

CIN1 is the lowest risk and does not require treatment, with women instead receiving regular follow-up appointments to be monitored.

Those with CIN2 cells will be given the option of follow-up checks or treatment to remove them, while the NHS recommends removal for high-risk CIN3 or CGIN cells.

In this study, Danish researchers followed 27,524 women between the ages of 18 and 40 who were diagnosed with CIN2 cells between 1998 and 2020.

They were followed from diagnosis until cervical cancer, hysterectomy, emigration, death or the end of 2020, whichever came first.

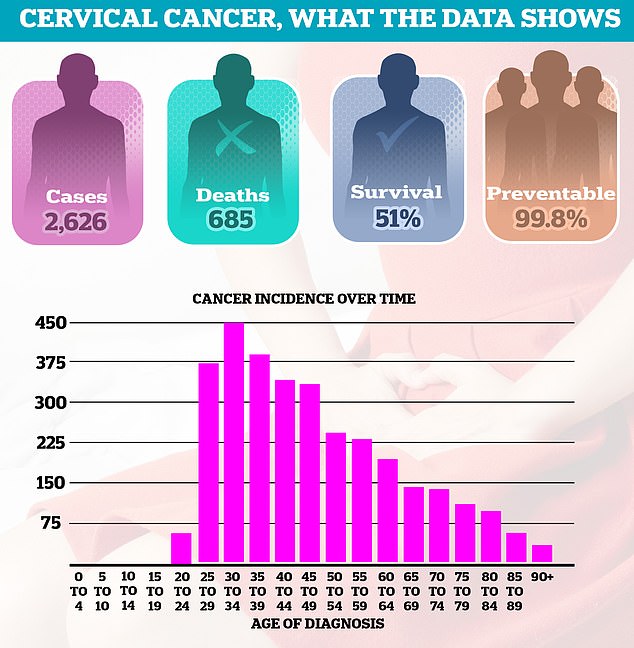

Thousands of women continue to be diagnosed with cervical cancer every year, leading to 685 deaths each year in England. About half of women (51 percent) survive 10 years or more after diagnosis. Diagnoses are most common in women in their 30s

About 45 percent opted to monitor abnormal cells, while 55 percent underwent large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), a common surgery to remove the affected cells.

Researchers found 104 cases of cervical cancer – 56 in the group that had the cells checked and 48 in the group that had LLETZ.

In the short term, the risk of cervical cancer was similar at 0.56 and 0.37 percent respectively during the two-year monitoring period.

However, in the long term, those who were followed saw their risk almost quadruple to 2.65 percent, while it remained stable among those who received treatment (0.76 percent).

The increased risk was mainly seen in women over the age of 30, according to research published in the BMJ.

Researchers said their findings are “important for future guidelines for the treatment of CIN2 and clinical management of women with a diagnosis of CIN2.”

It comes less than a fortnight after NHS England chief executive Amanda Pritchard pledged to eradicate cervical cancer by 2040, urging more women to attend screenings and stepping up efforts to vaccinate people against the main cause, HPV.

A spokesperson for the charity Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust said: ‘The study has provided a unique look at the long-term impact of monitoring CIN2 compared to immediate treatment.

‘Cervical cancer is a slow-growing disease that develops over five to twenty years.

‘However, the results highlight the importance of follow-up after a diagnosis of cell changes, and we would encourage all women and people with a cervix to attend their cervical cancer screening, colposcopy or follow-up appointments when invited.’