Roman wine was slightly SPICY with ‘aromas of toasted bread and walnuts’, scientists say

They were known for their love of wine.

But what did a glass of splash actually taste like in Roman times?

In a new study, researchers from Ghent University tried to answer this question by analyzing Roman dolia – the large clay jars that the Romans used for making wine.

Their analysis shows that Roman wine had a ‘slightly spicy’ taste, with aromas of toasted bread and walnuts.

And while it may not sound pleasant, the researchers say the wine would have caused a “drying sensation” in the mouth, which may have been desirable for the Roman palate.

They were known for their love of wine. But what did a glass of splash actually taste like in Roman times? Pictured: a statue of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine

In a new study, researchers from Ghent University tried to answer this question by analyzing Roman dolia – the large clay jars that the Romans used for making wine.

Previous studies have documented the Romans’ love of wine, which was fermented, stored and aged in dolia.

However, until now little was known about the appearance, smell and taste of this liquid.

“No study has yet closely examined the role of these earthenware vessels in Roman winemaking and their impact on the appearance, aroma and taste of ancient wines,” said the authors, led by Dr Dimitri Van Limbergen .

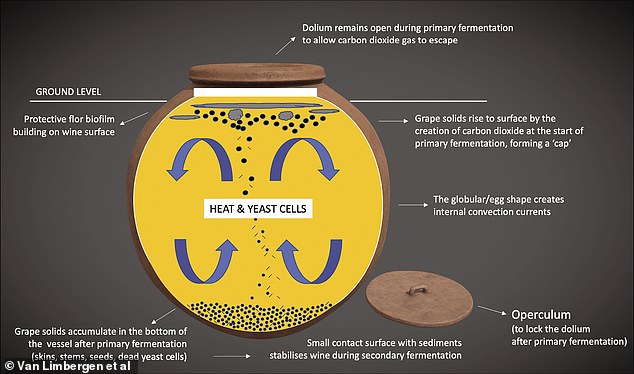

In their study, the researchers compared the Roman dolia with similar wine production vessels, called qvevri, that are still used in Georgia.

Their analysis suggests that several factors influenced the wine of the Romans, including the shape, material and storage of the barrel.

In terms of shape, the narrow bottom of the barrel prevents the grape solids from coming into too much contact with the wine as it ages.

According to experts, this extends the shelf life of the wine and gives it a ‘beautiful orange color’.

Meanwhile, by burying the dolia in the ground, the Romans could control the temperature and pH of the wine.

By burying the dolia in the ground, the Romans could have controlled the temperature and pH of the wine

This, according to the researchers, would have promoted the formation of surface yeasts and a chemical compound called sotolon, which would have given the wine a spicy taste and aromas of toasted bread and walnuts.

This, according to the researchers, would have promoted the formation of surface yeasts and a chemical compound called sotolon, which would have given the wine a spicy taste and aromas of toasted bread and walnuts.

Unlike today’s industrial containers, which are made of metal, the clay vessels of the Romans were porous, allowing oxidation during the fermentation process.

‘Unattended air contact turns wine to vinegar, but controlled oxidation can result in great wines because it concentrates color and creates pleasant grassy, nutty and dried fruit-like flavors,’ the researchers explain.

In addition, this mineral-rich clay would have given the wine a “drying feeling” in the mouth, which the researchers say might have been desirable for the Roman palate.

Overall, the findings suggest that the Romans knew what they were doing when it came to making wine.

“Far from everyday storage vessels, dolia were precisely designed containers whose composition, size and shape all contributed to the successful production of diverse wines with specific organoleptic characteristics,” the researchers concluded.