Roman chicken egg discovered in Aylesbury still has liquid yolk and egg white intact after 1,700 YEARS, scans confirm

A speckled egg dating back to Roman times still has its liquid yolk and white intact, new analysis shows.

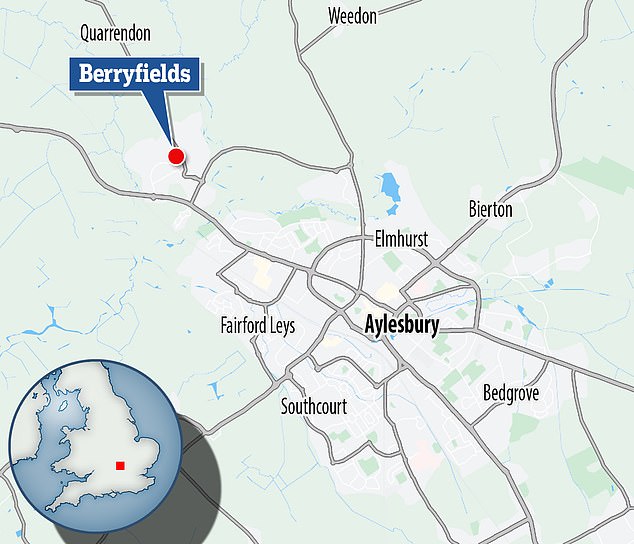

The ‘rare and exciting’ artefact, which is 1,700 years old, was found at Berryfields, north-west of Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire.

It was about 4cm wide and was located in a boggy pit, which is believed to have contributed to the egg’s incredible preservation.

Dana Goodburn-Brown, an archaeologist with DGB Conservation, performed a micro-CT scan on the egg, which showed it is still full of liquid and an air bubble.

‘It was an exciting moment when we first saw the bubble inside and then decided to turn the egg over and look again to see if the bubble would move, which it did,’ she told MailOnline.

An egg found in Buckinghamshire dating back to Roman times still has an intact liquid, new analysis shows

‘We decided it was best not to perform any invasive treatment on the egg because it is so rare and its contents are potentially of enormous scientific value.

‘Eggshells are porous and anything placed on the surface of the eggshell can also contaminate the contents inside.’

Eggshells have been found before at other Roman sites in Britain, but never a complete egg, let alone one with liquid preserved.

The egg was one of four discovered between 2007 and 2016 during excavations at Berryfields ahead of a new housing development.

They were part of an ‘extraordinary’ collection of objects, which also included a woven basket, earthenware vessels, coins, leather shoes and animal bones.

However, three of the eggs broke, releasing a ‘powerful stench of rotten eggs’, which those present described as ‘unforgettable’ and ‘incredibly sulphurous’.

Ms Goodburn-Brown said the egg was probably preserved by being placed in a waterlogged pit.

‘Organic materials and liquids do not normally survive the depths of time unless in special circumstances, such as when they are sealed off by clay or mud and no oxygen circulates,’ she told MailOnline.

The egg was one of four discovered between 2007 and 2016 during excavations at Berryfields ahead of a new housing estate

The eggs were part of an ‘extraordinary’ collection of objects, which also included a woven basket, earthenware vessels, coins, leather shoes and animal bones.

‘The boggy conditions at the Buckinghamshire archaeological site have preserved the eggs on site, as well as the nearby remains of a fragile wooden basket.’

Oxford Archaeology, which oversaw the excavations, said someone may have placed the eggs in the basket and in a Roman well for good luck, much like today’s wishing wells.

In Roman society, eggs symbolized fertility and rebirth, so it may have been linked in some way to another object placed there at the same time.

The egg was recently taken to the Natural History Museum in London to gather expert advice from Douglas Russell, the museum’s senior curator of bird eggs and nests.

Mr Russell said the “fascinating” and “possibly unique” object was likely “unintentionally preserved by the soil conditions in which it was found”.

‘There are older eggs with contents – for example the NHM has a series of mummified bird eggs, probably excavated by Sir Flinders Petrie in 1898 from the catacombs of sacred animals at Denderah, Upper Egypt, which may be older.

The team found four complete eggs in the well, but because they were so fragile, three broke, releasing a “powerful stench of rotten eggs,” he told the BBC.

‘However, this is the oldest unintentionally preserved bird egg I have ever seen. That makes it fascinating.

‘In the future it will be very exciting to see if we can use any of the modern imaging and analysis techniques available here at the NHM to shed more light on exactly which species laid the eggs and the potential archaeological significance of it.’

The egg is now housed in the Discover Bucks Museum in Aylesbury.

Researchers are now trying to extract the liquid contents from the egg without breaking the shell, but exactly how that will happen is another matter.

One option might be to make a fine incision in the shell to drain the contents, although this could lead to clogging.

“It’s a bit like blowing out an egg – but it’s clearly a much nicer process,” says Edward Biddulph, senior project manager at Oxford Archaeology. the BBC.

‘There is enormous potential for further scientific research and this is the next stage in the life of this remarkable egg.’