Revealed: How much MORE Britons on long-term sick leave earn than part-time workers as Britain’s sick note crisis deepens

People who come off long-term disability benefits and return to work could be up to £1,200 worse off per year than if they continue to draw, an analysis of the UK’s sick note crisis warns.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) found that someone working part-time for 16 hours a week or more on the National Living Wage (NLW) would see their income fall dramatically if their benefits are stopped.

They would have to work at least 22 hours a week before their income returned to the level they received through benefits.

And their income would only increase by £2,200 a year if they started working 35 hours a week at the NLW, earning £20,900 a year.

In contrast, a person on Universal Credit could get a financial benefit of around £3,500 in annual income if they work less than 16 hours a week at the NLW, a level called ‘restricted opportunities for work or work-related activities’ or LCWRA.

Analyzes show that more than four in five people who apply for disability benefits have not worked in the past two years

But if they exceed this threshold they could be reassessed by the Department for Work and Pensions and lose some of their Universal Credit, leaving them at a huge financial disadvantage when they start working.

Compared to what they would receive in benefits, this represents a potential loss of £5,000 per year.

In summary, the IFS said that this was a huge disincentive for benefit claimants on long-term sick leave to seek work above this threshold, and that many, fearful of accidentally falling over for some reason, will work even less.

It comes after it was revealed that more than four out of five people claiming disability benefits have not worked in the past two years.

According to the IFS, the figures illustrate the challenge the government faces as it seeks to get more people back to work and boost growth.

“The longer someone is out of work, the less likely they are to return to work,” the report reads.

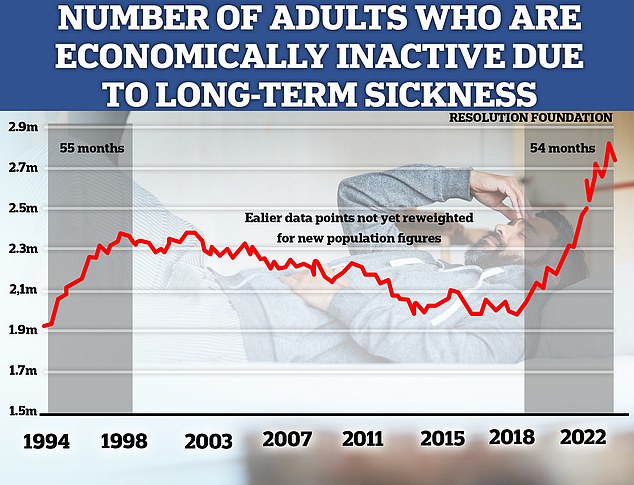

Separate official figures show the number of people out of work due to long-term illness fell slightly to 2.75 million, the lowest level in almost a year, although it remains close to record highs.

Britain has had the longest-running absenteeism epidemic for a quarter of a century, with the youngest and oldest workers driving the trend, recent analysis shows

The IFS said getting more disability benefit claimants back to work was an “understandable goal”, with the number rising 28 per cent since 2019 to 3.2 million.

IFS figures show that only 5.1 percent of disability benefit claimants were doing any work, while 82.9 percent had not worked in the past two years.

It also said that 83 percent of applicants had ‘the most severe level of disability’, meaning they are ‘likely still some way from returning to the labor market’.

Eduin Latimer of the IFS said: ‘There are unlikely to be easy solutions to the rising proportion of the population unemployed due to poor health.’

The news comes after an earlier report showed that unemployment due to long-term illness in parts of Britain has increased sixfold since pre-Covid.

In July, the number of people languishing at home due to illness peaked at 2.8 million, up from about 700,000 before the pandemic upended the country.

Rising rates of mental health problems have caused the ‘economic inactivity crisis’, which Labor has pledged to tackle as part of its plans to boost the economy and save taxpayers billions in benefits.

Shockingly, young people are now as likely to be unemployed due to long-term illness as those in their forties, according to the Resolution Foundation.

A MailOnline analysis of official statistics shows that it is estimated that more than 14 percent of Dover’s working-age population is now ‘economically inactive’ due to a long-term illness, or 9,700 people.

By comparison, in 2019-2020 this figure was almost 2.5 percent.

And earlier this year it was revealed that rising workplace illness is costing UK businesses an additional £30 billion a year, with the number of sick days doubling since 2018, a report has found.

Employees now report sick on average 6.7 days per year, compared to 3.7 days six years ago.

This means the annual cost of staff absenteeism has risen by £5 billion over this period, according to analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research.

However, the biggest costs to business come from ‘presenteeism’, where Britons turn up for work despite not feeling well and unable to give their best, the think tanks claim.

According to the report, the average worker now loses the equivalent of 44 days of productivity per year due to illness.

This is an increase on the 35 days since 2018, with the extra slack days boosting profits by £25 billion a year, researchers found.

IFS data also showed a 150 per cent increase in new disability claims among the over-40s in the past four years – and a sharp rise in mental health benefit claims.

The research highlighted how benefit claims are rising much faster in Britain than elsewhere – even though other comparable countries have also seen an increase in the number of reported disability cases.

It comes after Health Secretary Wes Streeting revealed the government wants to use fat-burning jabs like Ozempic to stimulate the economy and get unemployed, obese Britons back to work.

Weight-related diseases cost the economy £74 billion a year, with overweight people at increased risk of heart disease, cancer and type 2 diabetes.

The controversial plan has the backing of Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, who insists it could help ease demands on the NHS and boost the economy.

This is despite dire warnings that around 3,000 Britons have become ill after taking Ozempic and Wegovy so far this year.

The Prime Minister defended the drugs, telling the BBC: “I think these drugs could be very important for our economy and for health.”

He added: ‘This drug will be very useful for people who want to lose weight, need to lose weight, very important for the economy so that people can go back to work.

‘Very important for the NHS, because as I have said time and again, yes, we need more money for our NHS, but we need to think differently.

‘We need to reduce the pressure on the NHS. So this will help in all these areas.”

However, NHS chiefs have privately warned that the plan risks overwhelming an already overstretched service.