Revealed: Areas of England most vulnerable to measles outbreaks as children without a jab are at risk of three-week isolation due to an outbreak of infection

Four in 10 children in parts of England have not had a vaccine to protect against measles and are at risk of being locked up for three weeks.

Councils in England have warned parents that children who are not up to date on their measles jabs could be sent home for 21 days if there is a measles outbreak at their school.

Measles is a highly contagious and sometimes fatal disease that can infect nine out of 10 unvaccinated children in a classroom if only one classmate is contagious.

Although two doses of a vaccine called the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine are enough to provide 99 percent protection, uptake in the UK is dangerously low, especially in London.

In Hackney, 41 per cent of children have not yet been fully jabbed – the highest rate in the country – and could be told to limit their contacts for weeks if there is a case of measles at their school.

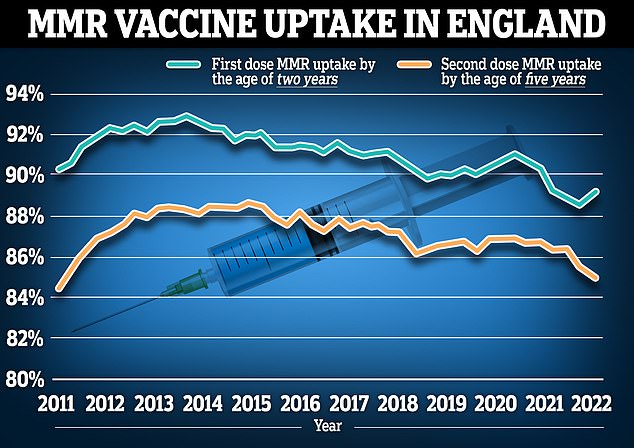

The graph shows the percentage of five-year-olds in England who have had both doses of the MMR vaccine. While the national average is 85.7 percent, in Hackney, North London, this figure drops to 59 percent.

Camden and Haringey, also boroughs in north London, were also among the areas with the lowest jab uptake: 37 and 35 percent respectively had not had both jabs.

In fact, the capital occupies the top 18 for most children not vaccinated against measles, while Liverpool only breaks the streak at 23.5 percent.

The low take-up rate of both MMR jabs, which stands at 85.7 per cent nationally and 74.2 per cent in London, prompted health chiefs to warn earlier this year that 160,000 cases of measles could occur in the capital alone.

Concerns about an outbreak have prompted city officials in recent months to send letters to parents warning that unvaccinated children could be excluded from school for 21 days in the event of an outbreak in their classroom.

London’s Barnet Council, which recorded 29 per cent of children unvaccinated, was one.

In a letter seen by MailOnline, they wrote: ‘We are currently seeing an increase in measles cases in neighboring London boroughs, so now is a good time to check your child’s MMR vaccination – which your protects the child not only against measles but also against mumps and rubella – is up-to-date.’

It continued: ‘Any child identified as a close contact of a measles case without satisfactory vaccination status may be asked to self-isolate for up to 21 days.’

Haringey Council, which had the third worst MMR uptake of all local authority areas in England, is also understood to have sent a similar letter.

Even municipalities that perform ‘well’ in the capital send out warnings.

Hertfordshire County Council, where only one in 10 children are not up to date with their MMR jabs, also warned parents that unvaccinated children face a 21-day exclusion period.

The 21 day isolation period is based on guidance published by the UKHSA in 2019.

It says if a case of measles is discovered, health teams will work with schools to provide advice on next steps for close contacts who have not had both MMR jabs.

This may include the offer of MMR vaccination, the provision of measles preventive medicines for close contacts of the child with vulnerable health conditions and possible exclusion for up to 21 days.

Siblings of an unvaccinated child who has been in close contact with a case of measles may also be asked to self-isolate.

Such exclusions would be the second time a virus has disrupted education in England in recent years.

Education was massively disrupted by the Covid pandemic, with schools closed or children forced into isolation because they were close contacts with an infected person, according to measures introduced at the time to combat the spread of the virus.

Given the low overall uptake of MMR in London, the capital has been at the center of efforts to encourage parents to come forward and get their child vaccinated.

However, NHS data shows that only two of almost 150 areas in England have achieved the target 95 per cent immunization rate, which vastly reduces the chance of an outbreak.

Data released earlier this year from NHS England shows that uptake of the MMR vaccine is just 89.2 per cent for one dose in two-year-olds, and 85.7 per cent for both jabs in five-year-olds.

These were County Durham in the North East (96 percent) and East Riding of Yorkshire (95 percent).

The 95 percent target ensures that a population effectively has herd immunity, preventing the diseases from spreading throughout the population.

Herd immunity is a crucial aspect of protecting people who cannot receive the MMR vaccine due to an allergy.

Nationally, only around 85 per cent of children have had both MMR jabs by their fifth birthday, meaning one in six will not have full protection by the time they start school.

The MMR shot, which provides lifelong protection against measles, consists of two doses and is 99 percent effective in preventing infections.

In Britain it is given first when a child turns one year old, and then again when the child is three years and four months old.

Measles, which usually causes flu-like symptoms and a rash, can cause very serious and even fatal health complications if the disease spreads to the lungs or brain.

One in five children who contract measles needs to go to hospital, while one in fifteen develops serious complications, such as meningitis or sepsis.

Part of what makes measles so serious is that it is highly contagious.

Health officials estimate that nine out of 10 unvaccinated children will develop the disease if just one child in their class is contagious.

Doctors are increasingly concerned that measles, long kept at bay thanks to these vaccines, could return due to declining uptake.

Acceptance of the MMR jab collapsed after research by the now discredited doctor Andrew Wakefield, who wrongly linked the jabs to autism.

Uptake of MMR in England was around 91 percent before the publication of Wakefield’s research, but fell to 80 percent in the aftermath.

Although the numbers have recovered slightly thanks to concentrated efforts by health officials, a rise in anti-vax sentiment during the Covid pandemic is believed to have contributed to some parents choosing not to have their children jabbed.

The latest data shows that 141 cases of measles have been recorded in England this year, up to July 31.

This is more than double the 54 cases recorded in all of 2022.

Of the 2023 cases, 85 (60 percent) were noted in London.

Only a fifth of cases were imported by an incoming traveler to Britain, meaning the rest were due to local community transmission.

Of the total cases, 58 percent involved children under the age of 10.