Research claims that ‘microaggressions’ contribute to one of the deadliest health problems in the US

People who experience sexism and racism are at greater risk for hypertension – a potentially fatal health condition.

A new study shows that women who experience microaggressions – indirect or subtle forms of discrimination – during pregnancy are at greater risk of dangerously high blood pressure.

Women who have recently given birth are already at increased risk for high blood pressure or postpartum hypertension, and in rare cases this can be life-threatening and lead to the development of heart disease later in life.

Researchers looked at about 400 women who had babies in Philadelphia and New York and reported that they experienced microaggressions while receiving health care during pregnancy and during childbirth.

Researchers found that 38 percent of Asian, Black and Hispanic women experienced at least one microaggression related to race and gender during or after their pregnancy.

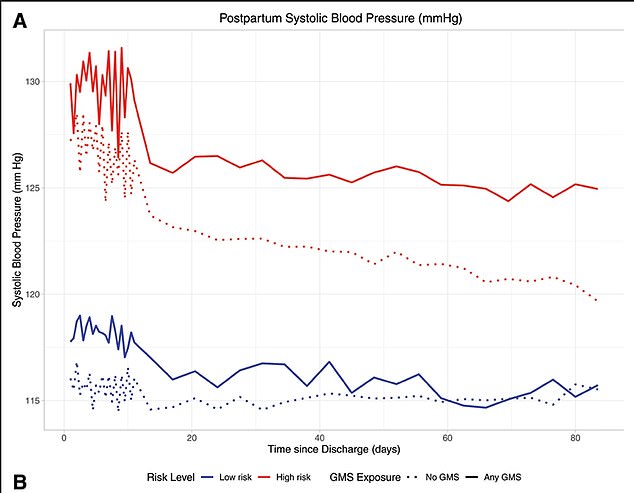

And those who experienced at least one race- or gender-based microaggression had blood pressure about two points higher three months after giving birth.

The link between high blood pressure and microaggressions was strongest 10 days or more after delivery, which poses an increased health risk because blood pressure is less likely to be monitored during this time.

Dr. Teresa Janevic, an epidemiologist at Columbia University and lead author of the study, said: ‘It is surprising that the associations were strongest in the later postpartum period, between twelve days and three months after delivery. This is an emerging critical period for preventing hypertension.”

Pregnant women who experienced at least one race- or gender-based microaggression before, during, or immediately after delivery had blood pressure about two points higher three months after delivery

Researchers gave pregnant women a blood pressure monitor to take home and use twice a day for 10 days, and then twice a week for 80 days.

A doctor reviewed the measurements and advised the women on how to lower their numbers if they ever became too high.

Meanwhile, women were asked to rate the frequency with which they encountered microaggressions — being told they had “pregnancy brain” or being labeled angry and rude when trying to get proper care — from “never.” to ‘once a week or more’. .’

Researchers also estimate structural racism at the community level with the Structural Racism Effect Index, a publicly available national index.

Blood pressure is measured in two digits in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg).

The first number (systolic) represents the pressure caused by the heart beating and pushing blood through the arteries, and the second (diastolic) is the pressure in the arteries as the heart relaxes between beats.

A healthy blood pressure for adults is 120/80 mm Hg.

Women who had experienced microaggressions during pregnancy had a systolic blood pressure that was 3 mm Hg higher than those who had not, and a diastolic blood pressure that was about one mm Hg higher.

The mean values for women who had experienced discrimination were 121/76 mm Hg, compared to 118/73 mm Hg for women without experience with microaggressions.

Experiencing microaggressions was linked to higher blood pressure after delivery. The difference in systolic blood pressure between people who experienced at least one microaggression versus none was more pronounced starting at 12 days postpartum and persisted for up to 3 months.

The difference may seem small, but it indicates the very real impact that microaggressions have on blood pressure and the associated risks.

Dr. Janevic said: ‘Our findings provide further evidence that healthcare professionals and policy need to focus more intensively on improving equity in maternal health care.’

Her team also found that the impact of microaggressions on blood pressure was more noticeable from 12 to 84 days postpartum, suggesting that these subtle expressions of racism and sexism have a lasting effect on a woman’s blood pressure over time .

When they looked further at both microaggressions and the level of structural racism where a woman lived, they found that those who experienced microaggressions and lived in areas largely divided by race had the highest average blood pressure three months after giving birth .

On the other hand, women who did not suffer from microaggressions and deep-seated racism had the lowest blood pressure after three months.

Dr. Janevic added: ‘We need monitoring and interventions for hypertension that extend further into the postpartum period, when blood pressure may remain sensitive to social health factors and to racial microaggressions.’

Overall, a CDC report found that in the US between 2020 and 2023, 48 percent of adults aged 18 and older had hypertension, which is about the same as the prevalence in the 2017-2020 CDC report.

Between eight and 16 percent of pregnant women suffer from high blood pressure, which if left untreated can cause life-threatening complications, such as heart disease and seizures in the mother, and premature birth and even death in the baby.

Black and Hispanic pregnant women are most susceptible to hypertension due to certain genetic factors and stress, as are women who live in rural areas where they are less likely to have access to prenatal care.

Older age is also a known risk factor for high blood pressure during pregnancy due to changes in hormone levels as a woman ages.

High blood pressure is a primary or contributing factor in more than 685,000 deaths per year in the US alone.

According to the CDC, high blood pressure was the leading cause of approximately 685,900 deaths in the US in 2022.

Normally hypertension does not cause any symptoms. That’s why doctors call it a “silent killer,” according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Over time, high blood pressure can weaken the heart and blood vessels, which can cause cardiovascular disease, including sudden cardiac arrest, and increase the risk of stroke and dementia.

To treat hypertension, doctors will recommend lifestyle changes such as achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, eating a healthy diet, reducing salt intake, limiting alcohol, exercising and making sure you get enough potassium, a mineral and electrolyte involved in important body processes. .