‘Professor Lockdown’ Neil Ferguson denies ever calling for lockdown but admits ‘stepping outside’ his SAGE advisory role

Britain’s Covid lockdown architect today denied he ever called for the country’s first national stay-at-home order.

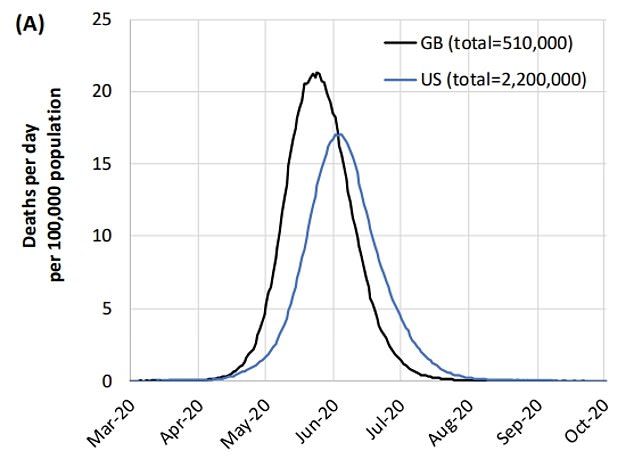

Professor Neil Ferguson’s terrifying modeling in March 2020 warned that 500,000 Britons would die unless tougher measures were taken to stop the spread of the virus.

It prompted Boris Johnson to adopt draconian restrictions, leaving the country told to ‘stay at home’. It would take months before vaccines – considered the only safe way out of the pandemic – are deployed.

But Professor Ferguson, who gave up his role as SAGE adviser two months after he was caught breaking social distancing rules to meet his married lover, today insisted he had not told officials the country was in lockdown to deposit.

He told the UK Covid-19 inquiry that the situation was ‘a lot more complex’.

Professor Neil Ferguson’s modeling in March 2020 for then Prime Minister Boris Johnson suggested that 510,000 people in the UK would die from Covid without drastic action

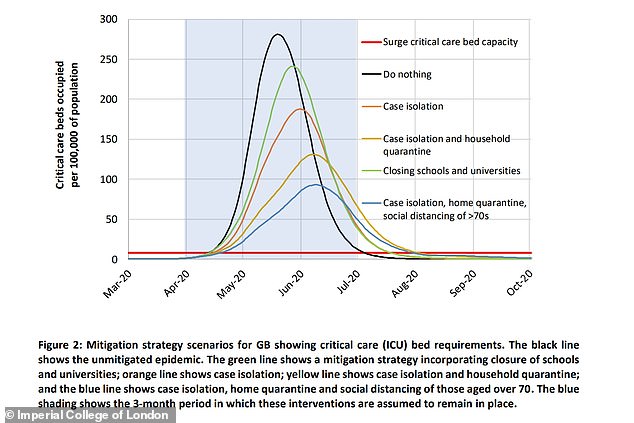

The epidemiologist was heavily criticized for his team’s modeling of the Covid pandemic. Their work suggested that 500,000 Britons would die if nothing was done to stop the spread of the virus (shown in the graph) and that 250,000 deaths would occur if two-thirds contracted Covid.

Imperial College London published a paper in March 2020 on the possible impact of the coronavirus. Options were being weighed on how a lockdown could reduce demand on hospitals

The research is in the second module, which examines the core of British decision-making and political governance.

Hugo Keith KC asked: ‘Do you feel that you have limited yourself to providing scientific advice, or, despite your best efforts, have you become irrevocably involved in determining policy?’

Professor Ferguson of Imperial College London, nicknamed ‘Professor Lockdown’ because of his infamous modeling work, said it was a ‘difficult question to answer’.

He said: ‘I know I’m very committed to some policy.

‘But as you will know from the evidence I have given in my statement and evidence, the reality was a lot more complex.

“I don’t think I crossed that line to say, ‘we need to do this now.’

“What I tried to do was occasionally, step outside the scientific advisory role, try to focus people’s attention on what was going to happen and the consequences of current trends.”

The epidemiologist was heavily criticized for his team’s modeling of the Covid pandemic.

Their work suggested that 500,000 Britons would die if nothing was done to stop the spread of the virus, and that 250,000 would die if two-thirds got Covid.

It caused then Prime Minister Johnson to end up in lockdown. It saw schools, shops and restaurants close, social distancing came into effect and Britons were only allowed to exercise outdoors once a day.

Experts largely agreed that the economically crippling measures were essential to control the spread of the virus, as there was no vaccine at the time to prevent severe illness and hinder hospitalizations.

But other epidemiologists and public health scientists shared their “serious concerns” about the collateral damage such policies will cause to the NHS and other parts of society in the future.

The wave was ultimately much less severe than Professor Ferguson had predicted, leading some to call the models ‘completely unreliable’.

Others insist the lockdown is the reason why cases have not reached the eye-watering levels set out in Professor Ferguson’s models.

He made other bleak models during the pandemic, later accepting that some were “wrong.”

Since the start of the pandemic, Britain has recorded 230,000 fatalities with Covid on the death certificate. Not all of these will be caused by the virus.

According to official figures, around 55,500 were registered in the first three months of the pandemic.

Despite resigning from his government role after his rule-breaking affair came to light, Professor Ferguson remained a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modeling (SPI-M) committee and the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG) .

It comes after a government scientist today told the inquiry that the number of Covid deaths during the first wave of the pandemic could have been lower if Britain had gone into lockdown just two weeks earlier.

Professor Steven Riley, who worked with Professor Ferguson at Imperial College London during the pandemic, said the lockdown should have been imposed on March 9, 2020.

The infectious disease expert, who now leads the data, analytics and surveillance group within the UK Health Security Agency, This data shows that people started changing their behavior on or around March 16, a few days before the stay-at-home order.

But he said government action should have been taken sooner.

“My view is that the first national period of strict social distancing (lockdown) should have been introduced on or about March 9, 2020,” he wrote in his witness statement to the inquiry.

Asked to explain this, he told the inquiry: ‘Once we had laboratory-confirmed deaths in ICUs (intensive care units) with no travel history, with no clear connections to social networks abroad, even a handful of those would indicate that we are spreading our epidemic progressing quickly.’

He added: ‘We have a lot of data on how social mixing has changed over this period and basically it seems that on or around March 16 everyone started to change their behavior.

“So I think the best way to talk about this is to say, if we had achieved that rapid reduction in mixing earlier than the 16th, then the peak height would have been lower, and the area under the curve for the first wave would have been smaller. and possibly a lot less.

“And the area under the curve is proportional to the number of deaths in a very crude but useful way.”

It comes as evidence submitted to the inquiry by a leading think tank suggests the NHS and social care in Britain are still ‘highly vulnerable to future shocks’ to the system.

The Health Foundation said in a statement that a “lack of health care capacity limited the response to Covid-19.”

“Without sustained investment in building resilience, the response to future health threats is likely to be similarly hampered,” the report said.

Britain entered the pandemic with fewer doctors, nurses, hospital beds and equipment than comparable countries, according to the think tank.

Meanwhile, funding growth for the NHS was ‘severely limited’ before the pandemic.

“Pre-existing limitations in our health and care system threaten to prolong the recovery of services after the pandemic and, without sustained investment, leave Britain highly vulnerable to future shocks,” the authors wrote.