Pope Francis is giving the strongest hint yet about where the Catholic Church stands on assisted dying

Pope Francis appears to have made his views on assisted dying clear in his New Year’s message, calling on the public to ‘respect natural death’.

The Pope has previously spoken out against assisted dying but remained silent on the issue ahead of the controversial vote in the British Parliament.

Still, during the New Year’s Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica on Wednesday, he called on everyone to make a “firm commitment to respect the dignity of human life, from conception to natural death,” while also taking a swipe at abortion.

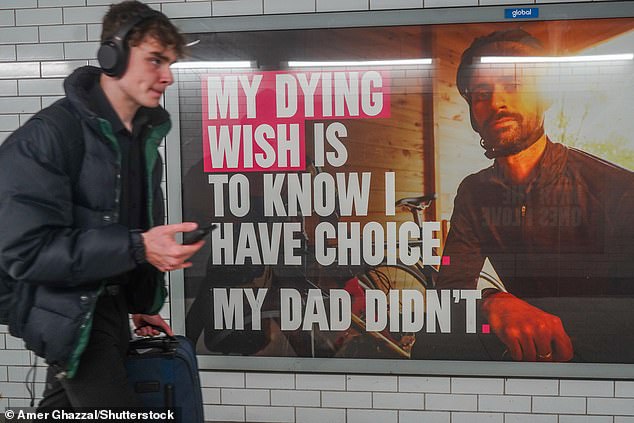

In November, MPs in Britain took the first step in passing one of the most historic pieces of legislation of the past decade, after five hours of emotionally charged debate.

The House of Commons approved the second reading of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which calls for the right of patients with less than six months to live to apply for assisted death in England.

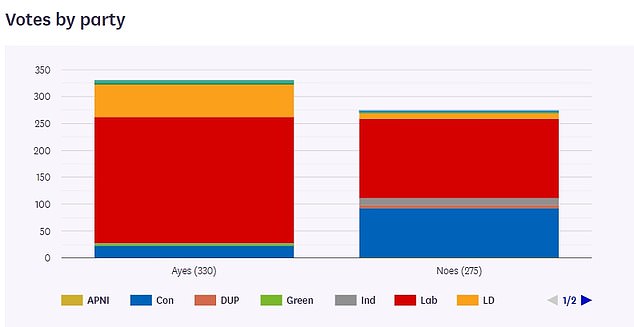

The result was achieved by a narrow majority: 330 votes in favor and 275 against, with Prime Minister Keir Starmer being one of the politicians in favor.

In his homily – a commentary that follows a reading from the Bible – the Pope said: ‘I ask for a firm commitment to respect the dignity of human life, from conception to natural death.

‘So that every person can cherish his or her own life and everyone can look hopefully to a future of prosperity and happiness for themselves and their children.’

The Pope has previously spoken out against assisted dying but remained silent on the issue ahead of the vote in the British Parliament

Still, during the New Year’s Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica on Wednesday, he called on people to “respect the dignity of human life, from conception to natural death.”

In November, MPs voted 330 to 275 in favor of assisted dying, although we won’t know whether the bill becomes law until later this year at the earliest.

He also called on people to protect “the precious gift of life, life in the womb, the lives of children, the lives of the suffering, the poor, the elderly, the lonely and the dying” and for “the eradication of death’. punishment in all countries’.

The Pope has become more outspoken in his opposition to abortion in recent years.

He called it “more than a problem: abortion is murder,” as well as “hiring a hit man to solve a problem.” In September, he branded Belgium’s abortion laws “murderous.”

Catholic leaders in England and Wales were among the most vocal opponents of a private member’s bill to legalize assisted dying, which was eventually passed in the House of Commons in late November.

That campaign was led by the Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Vincent Nichols, who called on believers to write to their MPs asking them to vote against the bill.

It is understood the Pope did not raise the issue with Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner when she met him at the Vatican just days before the vote.

But although the bill passed its second reading, assisted dying is not a certainty in England.

A total of 235 Labor MPs supported the bill, alongside 23 Tories, 61 Liberal Democrats and three Reform MPs from the UK.

Catholic leaders in England and Wales were among the most vocal opponents of a private member’s bill to legalize assisted dying, which was eventually passed in the House of Commons.

A total of 236 Labor MPs supported the bill, alongside 23 Tories, 61 Liberal Democrats and three Reform MPs from the UK.

Kim Leadbeater told fellow MPs that her Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill will give people ‘choice, autonomy and dignity at the end of life’.

This compared with 147 Labor MPs who opposed the bill, along with 93 Tories, 11 Lib Dems and two UK reform MPs, including party leader Nigel Farage.

During the five-hour debate in the House of Commons, MPs on both sides made passionate arguments, with supporters saying they wanted to offer ‘choice’ to those in ‘excruciating pain’.

But opponents warned against the introduction of a ‘state suicide service’ for terminally ill people.

The nation won’t know until later this year at the earliest whether assisted dying will be enshrined in law.

This is because the bill now moves to a committee stage where MPs can table amendments, before it faces further scrutiny and votes in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Labor MP Kim Leadbeater, who introduced the bill to Parliament, has also said it is likely to be another two years before an assisted dying service is in place.

The bill contains a number of provisions about who can seek help in ending their lives, and how they can do so.

First, two independent doctors must confirm that the patient meets the following criteria.

Those eligible must be over 18 years old, live in England and Wales and be registered with a GP in the past year.

It must be assumed that they have the mental capacity to make the choice to end their lives, and that they should not be pressured by others to do so.

A medical team must have calculated a bleak prognosis: less than six months.

To ensure that the decision has been properly considered, the patient must also make two separate statements about their wish to die.

If doctors believe the patient is eligible, the case is referred to a Supreme Court judge, who makes the final decision.

At least two weeks after a positive ruling, a patient may commit suicide with the help of a doctor.

But concerns have been raised that ‘gaps’ in the legislation could put vulnerable patients at risk of ill-considered decisions.

In November, for example, it emerged that doctors are allowed to raise the subject of assisted suicide with patients, even if they have not said so themselves.

And anyone who needs assistance in dying is allowed to shop around until he or she finds a doctor who will sign off on his or her request if his or her first choice can’t or won’t do the job.