Pennsylvania sits on a vast, untapped lithium ‘white gold mine’ that could generate a new multibillion-dollar industry, a government study shows

Pennsylvania could become the center of America’s new ‘white gold rush’ with the discovery of a major untapped source of lithium in the state.

Government scientists have shown that they can filter the precious metal from the state’s shale gas wastewater: they can extract tons of lithium per day, while leaving little behind.

They concluded that Pennsylvania alone could produce nearly half of the entire U.S. demand for lithium from the first year, supplying this important compound needed to power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles to solar panels.

A project on this scale could turn Pennsylvania into a rust-belt Saudi Arabia, ending U.S. dependence on lithium from China, which now controls 90 percent of the market.

And unlike many new lithium mining proposals, which have threatened scarce water supplies from Arkansas to Colorado, this process would make a virtue of the high-pressure water already used in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, of natural gas.

With 72 proposed lithium mines in the US, the discovery could help reduce local ecological impacts as America moves away from ‘greenhouse gas’ emitting fossil fuels.

According to the new research, produced in collaboration by the US National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) and the University of Pittsburgh, more than 1,200 tonnes of lithium could be recovered annually from Pennsylvania’s ‘fracking’ wastewater.

“Wastewater from oil and gas is a growing problem,” as a government geochemist behind the new research put it. ‘We are looking at a useful use of that waste.’

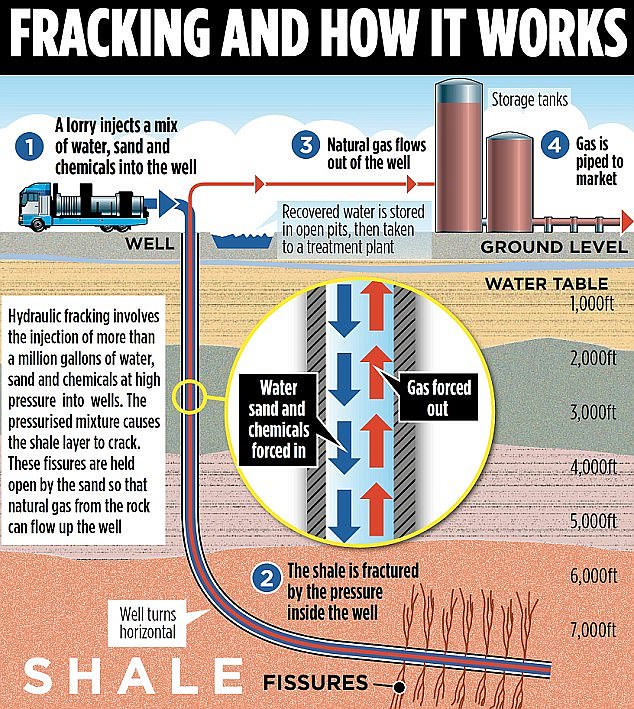

Fracking is a process used to extract natural gas from deep underground shale rock through the injection of more than a million gallons of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure into artesian wells.

The pressurized mixture tears open the shale rock, creating new fissures that are held open by the sand, allowing natural gas to flow from the rock into the well.

Despite reducing U.S. dependence on foreign oil, fracking has proven highly controversial due to its use of chemicals, groundwater contamination, noise pollution, air pollution and even its ability to cause earthquake-like tremors.

And these risks have become a hotly debated topic in Pennsylvania, where fracking has been linked to other health problems.

According to the new research, produced in collaboration by the U.S. National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) and the University of Pittsburgh, more than 1,200 tons of lithium could be recovered annually from Pennsylvania’s fracking wastewater.

Although the price of lithium in this volatile new market fluctuates, the state’s annual revenue from this wastewater lithium could range from $1.6 million to $18 million at current prices.

Fracking is the process of drilling into the earth before introducing a high-pressure water mixture to release natural gas. Water, sand and chemicals are injected into underground boreholes at high pressure to open cracks in the rock, releasing trapped natural gas

Although the price of lithium fluctuates in this volatile new market, the annual return for the state at current prices could range from $1.6 million to $18 million.

Even more promising is that their projection that this wastewater recycling could meet nearly half of U.S. lithium demand does not take into account any nearby activity in other states.

The so-called Marcellus shale region, where an estimated 144 trillion cubic feet of natural gas lies between two enormous layers of limestone, covers much of Pennsylvania – but also extends into New York, Ohio and West Virginia.

‘Pennsylvania has the most robust data source for Marcellus shale,’ says NETL geochemist Justin Mackey said in a statement. “But there’s also a lot of activity in West Virginia.”

Mackey and his colleagues were able to calculate the likely amount of lithium floating in solution in this fracking wastewater through pollutant reports that every oil and gas company in Pennsylvania must file with regulators.

“Lithium is one of the substances they have to report,” Mackie said. ‘This is how we were able to carry out this regional analysis.’

Based on their estimates, which were published in the journal in April Scientific reportsfracking wells in the southwestern part of Pennsylvania appear to contain almost twice as much lithium as wells elsewhere in the ‘Keystone State’.

Geochemist Justin Mackey and his colleagues were able to calculate the likely amount of lithium floating in solution in this fracking wastewater from pollutant reports that every oil and gas company in Pennsylvania must file with regulators.

Although geologists have long known that lithium was present in the mineral content surrounding these shale gas deposits, an accurate estimate only became feasible as years of these mandatory reports came in.

“There had not been enough measurements to quantify the resource,” Mackey explained. “We just didn’t know how much was in there.”

But there was an accidental benefit, because lithium-based mineral compounds such as lithium chloride and lithium carbonate are water-soluble.

The simple act of injecting fracking wells with high-pressure water has led to much of that lithium metal being pulled out of the rock and into the fracking wastewater.

Water in underground aquifers has, as Mackey put it, “been dissolving rocks for hundreds of millions of years.”

“Essentially the water has mined the subsoil,” he said.

America has about eight million tons of lithium in its country, meaning the U.S. industry is worth about $232 billion.

However, the country only accounts for about one percent of global lithium production China has dominated the market for decades because 90 percent of the metal mined is refined in their country.

But the reckless exploitation of America’s lithium resources could come at a high cost, experts warn.

About 40 of the 72 proposed US lithium mines are earmarked for Nevada, America’s driest state, and 80 percent of them would rely on water supplies at risk of low water levels, according to an analysis by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

Jeff Fontaine, executive director of the Central Nevada Regional Water Authority, told researchers at the Howard Center that excessive water use in the basin can cause “permanent” damage underground and “a combination of things that can prevent the aquifer from ever really healing itself.” will recover.’

Poor planning for such mines, the Howard Center noted, could harm local communities and wildlife that need access to the freshwater of these aquifers.

Patrick Donnelly, a conservation biologist for the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, told the Howard Center that if all 72 proposed mines were built under current rules, “this would be a fundamental transformation of the American West.”

“People compare it to the Gold Rush, but the Gold Rush was quite small-scale compared to what all this lithium looks like,” Donnelly said.