Parents across the country say children are struggling in school and fighting more without ADHD meds

Persistent Adderall deficiency has prevented children from concentrating and behaving in school, according to parents in the US.

Parents and school officials across the US, from California to Kentucky to Massachusetts, are concerned about declining rates and rising violence among children who are suddenly withdrawing from drug use.

The Food and Drug Administration acknowledged the shortage last October, but parents of children with ADHD have been sounding the whistle about supply chain problems and backorders since the summer.

Giving children drugs for ADHD is the norm in the US, and of the more than six million of those who have the condition, more than 60 percent are on drugs such as Adderall. But over the years, concerns have grown in the medical community about the overprescription of potentially addictive drugs.

Adderall, perhaps the most commonly prescribed ADHD medication in the US, has been banned in many European countries as well as Japan.

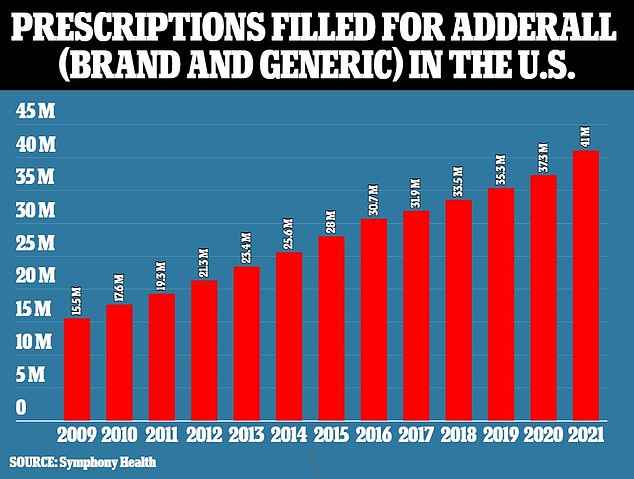

Doctors in comparable countries seem to be less eager to prescribe the drugs. While a whopping 41 million Adderall prescriptions were dispensed in the US in 2021, the UK National Health Service dispensed a total of just 2.23 million ADHD drugs from July 2021 to June 2022.

Adderall was officially recognized by the FDA as a deficiency drug in October, but many parents have struggled to get their children’s prescriptions since last summer

Adderall prescriptions have steadily increased over the past 12 years. The numbers include prescriptions for both Adderall, brand and generic, in the US

Prescriptions for Adderall surged during the COVID-19 pandemic. In February 2020, just before the virus broke out across America, the drug made up 1.1% of drugs. By September 2022, the figure had more than doubled to 2.31% of all scripts written

Yet there have been reports across the country of children misbehaving in class, disrupting fellow students and receiving increasing disciplinary calls to parents over the past year.

The ongoing problem is attributed to labor and supply shortages at Israel-based Teva Pharmaceuticals, which last year made one in four branded and generic Adderall pills dispensed in U.S. pharmacies.

It is also related to the rising number of new prescriptions handed out during the pandemic, as telehealth services proliferated and more bad actors were able to deliver the drugs to people with little to no consultation.

A Washington mom has blamed lax Adderall regulations brought in during the Covid pandemic for her son Elijah’s suicide last year. The young man who died at the age of 21 had abused Adderall in the months leading up to his death.

His mother, Kelli Rasmussen, said that despite her son not having Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), he was able to get a prescription online through the controversial mental health start-up Cerebral by lying to telehealth providers — even though he had more likely to suffer from other mental health problems.

Massachusetts mother of four Samm Davidson detailed her seven-year-old son’s difficulty doing well in school after not having his generic form of Adderall.

Ms Davidson said: ‘However, today I read an email about his increased folly and inability to pay attention. He blurts out answers, distracts colleagues in small groups, and has trouble completing assignments.

“And while disappointing, the email doesn’t come as a surprise… my son has been out of prescription for four days in a row, which is very impactful.”

ADHD medications treat a deficiency of certain neurotransmitters, specifically dopamine and norepinephrine, which are involved in attention and focus.

An estimated six million children ages 3 to 17 have ADHD.

Of that total, about 62 percent take medications to manage symptoms, including the inability to sustain attention and listen to others, impulsive actions such as interrupting others, and hyperactive behaviors such as constant movement with no apparent purpose.

Ms Davidson continued: ‘My son’s learning is directly affected by this problem. He relies on his prescription medication to focus his mind and calm his body to be successful in a learning environment… So randomly withholding it for days at a time feels so unfair to his little seven-year-old brain.”

In Marana, Arizona, Jennifer Paul, a mother of seven-year-old twin daughters told the Wall Street Journal that the shortages have created “hell” for her family. Her daughters were running out of medicines and could not get new medicines for about a week a month, causing them to drop out at home and school.

Ms. Paul said, “They beat teachers, throw garbage, destroy the classroom… They can’t concentrate.

“It has caused a lot of problems in our family. No one wants to be around us when they’re displaying that behavior.”

In the meantime, in Aurora, Colorado, the Hahn family struggles to find Adderall for their 6-year-old son, Troy. His father, Phil Hahn, said he has tried to fill Troy’s prescription for Adderall at at least 20 different pharmacies.

Mr Hahn said he sees behavioral changes in his son, even citing changes in Troy’s handwriting as evidence of the impact not being on the medication has had.

Adderall contains a combination of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine.

It works by increasing the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain, which helps improve focus, attention, and impulse control in individuals with ADHD.

Earlier this year, the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 64 percent of community pharmacists reported difficulty getting Adderall.

And without it, students have a hard time.

In Georgia, Kristina Yiaras searched an extensive list of pharmacies within a 50-mile radius of her home in Kingsland in a fruitless attempt to meet her eight-year-old son’s prescriptions.

Mrs Yiaras told NPR: “As soon as it was over, he was in trouble every day, getting up from his chair… The teachers noticed right away that he was off.”

The FDA has approved several medications to treat ADHD, the most common and trusted of which are stimulants, strictly controlled drugs by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

There are only two stimulant drugs: methylphenidate (the active ingredient in Ritalin, Concerta, and other formulations) and amphetamine (the active ingredient in Adderall, Vyvanse, and other formulations).

But because of its high potential for abuse, the DEA has classified it as a Schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act.

This means that the agency chooses annual quotas for producing the drugs based on historical data. But critics of the agency claim it has not updated its quotas to reflect increased demand in recent years, creating a shortfall.

Demand for the drugs has skyrocketed in recent years, which many blame on the advent of telehealth services during the Covid pandemic leading to an increase in prescriptions.

Health data company Trilliant Health reported last summer that adult Adderall prescriptions are up 15.1 percent in 2020, double the 7.4 percent increase in the previous year.

Diagnoses of behavioral problems increased during the Covid pandemic as people suddenly thrust into a world of isolation struggled with massive lifestyle changes, financial insecurity, a transition to working from home and, in some cases, becoming homeschool teachers at nightfall. a hat.

The over-prescribing of Adderall, a common party drug, is also a major problem. So much so that the controversial mental health startup Cerebral has been targeted by the Justice Department for possible violation of the Controlled Substances Act by overprescribing drugs such as Adderall and Xanax for anxiety.

Today, some 41 million Americans have a prescription for Adderall, a 16 percent increase from pre-pandemic levels. Last year four million new patients received prescriptions, a doubling compared to the previous year.