Panic over immortal sea creature that can create a form of cancer that’s contagious

A tentacled jellyfish-like creature has now been discovered that can pass on cancerous tumors to its offspring.

French government scientists studying this “brown hydra,” named after the lake monsters of Greek mythology, have raised concerns that their “transmissible cancers” could have “drastic ecological consequences” if they were allowed to spread into the wild.

Although brown hydras have only developed these tumors in the laboratory, the phenomenon has nearly driven the Tasmanian devil to extinction off the coast of Australia in the past decade.

Researchers are now concerned that pollution could lead to more contagious forms of cancer, but it is still unclear whether similar forms of the disease can also affect humans.

A freshwater carnivore known for its one-inch tentacles and ability to live forever – the brown hydra – has now been found to be capable of passing cancerous tumors on to its offspring

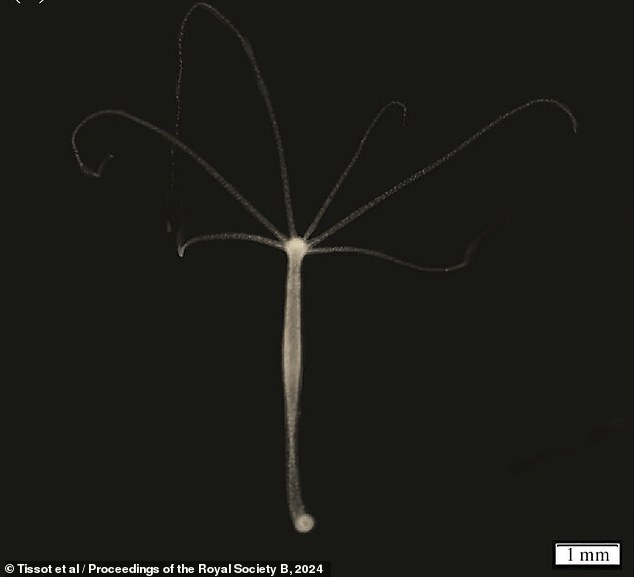

Above is a tumor-free example of the brown hydra from the researchers’ laboratory population, cultured from samples obtained from Lake Montaud in the south of France

“Human activities may unwittingly create conditions that promote the spread of these cancers,” said the study’s lead author, evolutionary ecologist Sophie Tissot.

Before the new investigation, which was published on Tuesday in the Proceedings of the Royal Society BBoth cancer researchers and biologists assumed that these infectious cancers could only arise from a rare “perfect storm” of host and cancer cell properties.

But the new findings from the French national research agency, the national centre for scientific research (CNRS) have shown that transmissible cancers can simply arise from overnutrition.

Tissot and her colleagues fed their laboratory colonies with brown hydra (Hydra oligactis) larval shrimp (Artemia salt plant) for both the control group and the experimental group.

The choice was reminiscent of the kind of human activities, such as aquaculture, that in the real world can lead to overfed blooms of gorging little brown hydras.

Hydra ‘can occasionally grow to large numbers’, according to a field guide by the Missouri Department of Conservation.

“And when this happens in fish farms,” the U.S. state agency warned, “they can pose a serious threat to newly hatched fry. [baby fish or shrimp].

Before this study, the brown hydra had already attracted the attention of biologists who study freshwater ecosystems because of the creature’s seemingly infinite lifespan.

Brown hydras are not only resistant to aging, but can also regenerate damaged tentacles.

Fortunately, Tissot and her team also discovered that these transmissible cancers were often “vulnerable” and could go into remission if they fed their brown hydra less.

Her CNRS group and other transmissible cancer researchers now hope to use Hydra’s rapid life cycle to better understand transmissible cancers in the lab.

“It’s certainly a more manageable system than keeping 1,000 Tasmanian devils in the lab and watching them to see if they develop cancer,” biologist Michael Metzger told the journal’s news desk Science.

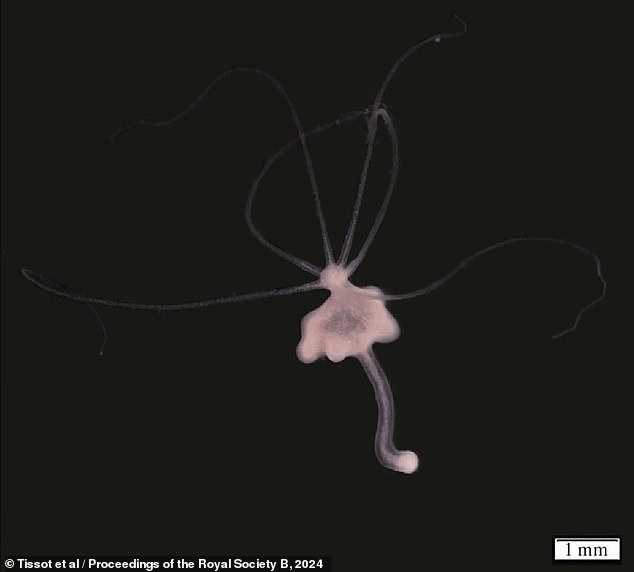

Above is an image of one of the study’s brown hydras that developed the transmissible tumors – visible as bumps along what would normally be its long, thin body. The team behind the new researchers took these images using a camera-mounted, or trinocular, microscope

“Human activities may unwittingly create conditions that promote the spread of these cancers,” said the study’s lead author, evolutionary ecologist Sophie Tissot. According to the Missouri Department of Conservation, hydra blooms can contaminate shrimp and fish farms

Metzger who studies the evolution of cancer at the Pacific Northwest Research Institute in Seattle, Washington, described the brown hydra’s potential to revolutionize cancer research as “really interesting.”

‘You can really learn a lot [from them] “About fundamental aspects of cancer biology,” said Metzger, who was not involved in the new study.

Tissot and her colleagues at CNRS were able to induce cancer in their experimental groups of brown hydra in less than two months. They also followed four to five generations of the small carnivorous animal to see which infectious tumors were passed on.

Thanks to their control groups and knowledge of the hydra’s genetic predisposition to cancer, the team concluded that a “contagious” tumor was the most likely explanation for why successive generations of creatures inherited their parents’ tumors.

“If this conclusion is confirmed in the future,” Tissot and her team wrote, “it will be crucial to take these aspects into account when studying ecosystems disturbed by human activities.”

Human activities, similar to a shrimp or fish farm being ravaged by a voracious brown hydra, could “potentially alter the conditions that favor the spread of transmissible cancers.”

Metzger noted that it is too early to predict what the discoveries about the brown hydra’s transmissible cancers mean for the form of the disease in humans.

“They’re a little bit different than what happens in people,” he cautioned, “but I think that’s their value. It shows the breadth of what cancer can look like.”