One small step for mice, one giant leap for mankind: Scientists grow mouse embryos on the International Space Station for the first time, paving the way for humans to reproduce in space

Hopes of a future human space colony may move a step closer after scientists successfully grew mouse embryos for the first time on the International Space Station (ISS).

Researchers from the Japan Aerospace Space Agency and Yamanashi University sent frozen embryos to the ISS, which were then thawed and cultured for four days.

The scientists found that the embryos developed normally in low gravity and showed no signs of DNA damage from radiation.

Their breakthrough is important because it suggests that human reproduction could be possible outside the influence of Earth’s gravity.

“There is a possibility of pregnancy during a future trip to Mars because it will take more than six months to travel there,” said lead author Teruhiko Wakayama of Yamanashi University in Japan.

Researchers sent specially frozen mouse embryos to the ISS to test whether humans could possibly reproduce in space

“We’re doing research to make sure we can safely have children when that time comes.”

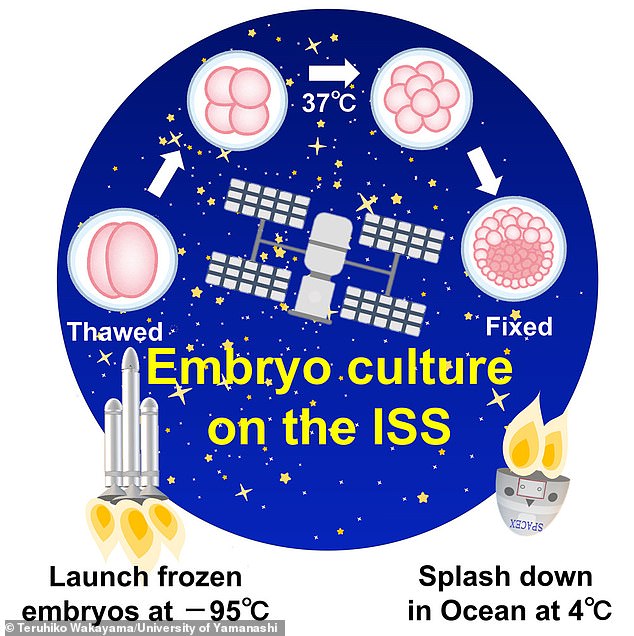

The mouse embryos were carefully extracted and frozen to -95°C (-139°F) in laboratories on Earth before being sent to the ISS aboard a Space X rocket in August 2021.

They were placed in a special device designed to easily thaw the embryos upon arrival.

After four days of development, the longest time they could survive outside the womb, the cells were chemically preserved and returned to Earth.

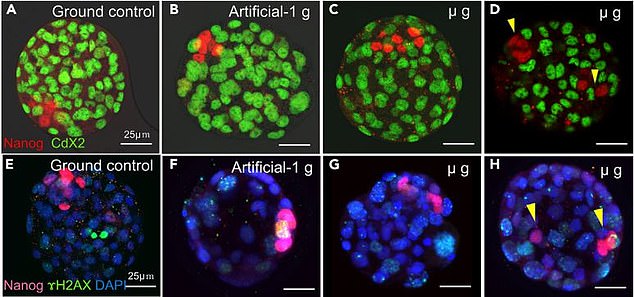

The researchers found that the embryos developed normally into cell types called blastocysts, which develop into the fetus and placenta.

Scientists were previously unsure whether mammalian embryos could develop well in microgravity.

During the early stages of fetal development, embryos develop into two different types of blastocysts: one that forms the placenta and another that forms the fetus.

However, the cells that contribute to the formation of the fetus always cluster in one spot, possibly because they are heavier and sink in place.

The concern was that the blastocysts would not be able to sink in microgravity and that fetal formation would be disrupted, if not impossible.

Embryos were extracted by scientists on Earth, frozen with liquid nitrogen and sent to the ISS, where they were thawed and grown in zero gravity for four days

Dr. Wakayama said the results showed that mammals could one day reproduce in space.

“Based on (this) and our results, mammalian space reproduction may be possible,” he added.

In a joint statement, Yamanashi University and Riken National Research Institute said the experiment “clearly showed that gravity had no significant effect.”

They added that the study was “the first-ever study to demonstrate that mammals can thrive in space.”

Looking ahead, researchers say they now plan to test whether mouse embryos returned from the ISS can be implanted into female mice and produce healthy offspring.

They also want to test whether mouse eggs and sperm sent to the ISS can be used to create viable embryos.

This would provide more information about whether the effects of microgravity and radiation disrupt mammalian reproductive systems.

However, the scientists say it is unclear whether mammals could give birth in space.

The findings come amid a broader push to allow humans to travel further into space and possibly set up permanent colonies.

Under its Artemis program, NASA plans to send humans back to the moon to learn how to live there long-term in order to prepare for a trip to Mars, sometime by the end of the 2030s .

Even under microgravity, the mouse embryos were able to divide normally and differentiate into the different types of cells needed to form an embryo and a placenta.

Recently, NASA astronaut Frank Rubio returned to Earth after the longest space flight ever by an American.

After spending 371 days in orbit, Rubio was exposed to the harmful effects of microgravity and space radiation, which can be very harmful during long stays in space.

While an astronaut on the space station could experience up to 250 times more radiation than on Earth, a trip to the moon or Mars would expose him to up to 750 times more radiation.

Although the mouse embryos showed no signs of radiation damage, the researchers suggest this could be due to the short time they spent in space.

In future attempts by humans to live or reproduce in space, there is a high risk that they will suffer from the adverse effects of this radiation.

The new study has been published in the journal iScience.