Netflix users hooked by new documentary about cursed 2,200-year-old tomb in China that experts dare not open

Netflix viewers can’t get enough of the necropolis of China’s first emperor — though archaeologists have long worried about the dangers of opening his still-sealed tomb.

Toxic rivers of liquid mercury, built like a miniature map of the emperor’s kingdom, are just one of many potential risks when opening this inner sanctum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi’s tomb.

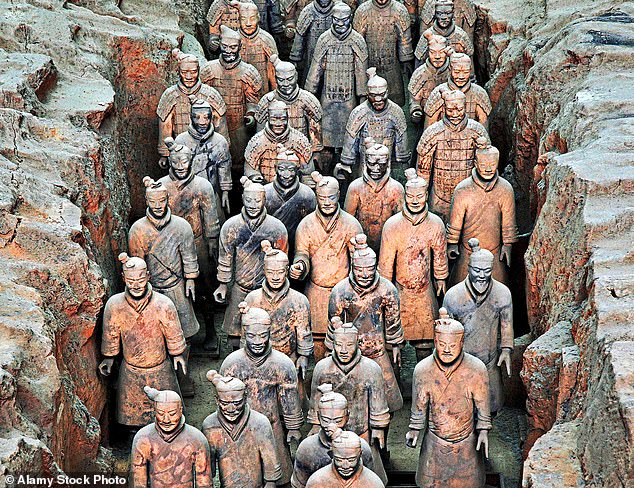

Experts are also concerned that exposing the sealed army of clay-sculpted “terracotta warriors” to the open air has caused the paint of similar sculptures buried close to the emperor’s more than 2,200-year-old tomb to immediately peel and evaporates.

Researchers have even turned to an exotic X-ray-like scanning technique called “muon tomography,” which harnesses cosmic rays from space to peer into the sealed-off cemetery.

But of course there are also rumors that there is a curse on the grave, and certainly the seven local villagers who unearthed the first of Qin Shi Huangdi’s nearly 8,000 buried clay warriors in 1974 paid a high price for their discovery.

Netflix viewers can’t get enough of the necropolis of China’s first emperor — even though archaeologists have long worried about the dangers of opening his still-sealed tomb

Poisonous liquid mercury rivers, built like a miniature map of the emperor’s kingdom, are just one of the potential risks of opening the inner portion of Qin Shi Huangdi’s tomb. But there are many more that worry scientists and excavators, including rumors of traps and even a curse

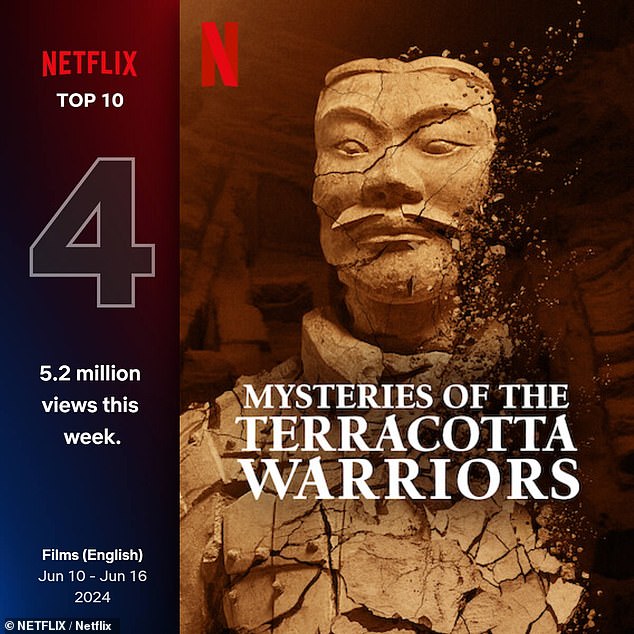

‘Mysteries of the Terracotta Warriors’ reportedly had 6.8 million hours watched, climbing to fourth place on the streamer’s ‘Most Watched’ list this week since the one-hour, 17-minute documentary debuted on Netflix on June 12 .

British director James Tovell’s stunning documentary explores the life, death and archaeological legacy of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (259–210 BCE), who succeeded in conquering and uniting all of China in 221 BCE.

Qin Shi Huang created an empire that lasted about two millennia.

And his other achievements included starting construction on the Great Wall of China, establishing a nationwide road network, and standardizing writing and units.

But the discovery of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi’s clay soldiers – sculpted to serve as his army in the afterlife – proved less of a success for the seven men who discovered Qin’s first known terracotta warriors.

These villagers in a farming community near the city of Xi’an found the clay head of a warrior while digging a new well during the devastating drought of 1974.

A frenzy ensued from the moment this pottery-like clay head and the several bronze arrowheads unearthed with it were first made public.

Soon the village’s agricultural land was confiscated by the government for its archaeological and historical value.

And over time, houses were demolished to make way for museum halls and tourist shops.

Three of these seven farmers died under tragic and terrible circumstances.

Wang Puzhi, then 60, hanged himself with a rope in 1997 after facing prohibitive medical bills to treat his illnesses.

Two more farmers died in their early fifties, Yang Wenhai and Yang Yanxin, equally destitute and unable to pay for their own health care.

Netflix’s new documentary ‘Mysteries of the Terracotta Warriors’ reportedly had 6.8 million hours watched, rising to fourth place on the streamer’s ‘Most Watched’ list this week

The rest lived by earning less than a few dollars a day and signed books for tourists for years at the official souvenir shops in front of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor.

One of the surviving farmers, Yang Zhifa, was so disgusted by his treatment that he did not view the restored army of statues until 1995, he said. China daily.

Although the discovery of the tomb remains one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century, attempts to delve deeper into the tomb face difficult obstacles.

Testing of the soil around the site has revealed traces of mercury 100 times higher than normal, lending credence to the myth that Qin had crafted rivers and lakes full of the element built in front of his tomb as part of a giant map of China.

“Every time we excavate something there will be a lot of risk assessment.” Ming Tak Ted Huian Associate Professor of Classical Chinese and Medieval China at the University of Oxford, told DailyMail.com earlier this June.

Above, a 2,200-year-old terracotta army at the Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses Museum in Xi’an

“But if we look at the trend, I can say that there seem to be more opportunities to actually do that,” said the researcher, who appears in the new Netflix doc.

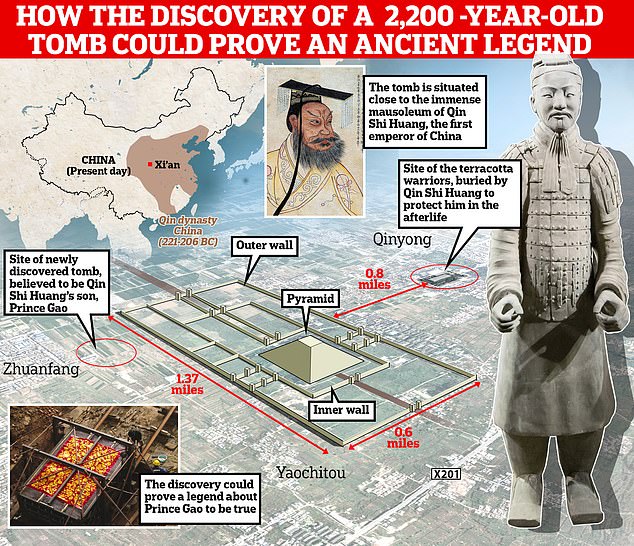

He added that while better technology makes it easier for researchers to dig carefully, the graves in Xi’an, which may contain one of the emperor’s heirs, Prince Gao, may have the added challenge of falling.

The existence of these traps was explained in the work of the ancient historian Sima Qian, writing around 85 BC.

According to Sima Qian (145–86 BCE), the official historian of the Han dynasty, the emperor’s necropolis complex contained “palaces and picturesque towers for a hundred officials,” all of which were carefully protected.

Qin’s underground tomb itself “was filled with rare artifacts and beautiful treasures,” this Han historian wrote, and to safeguard those treasures, “craftsmen were commissioned to make crossbows and arrows ready to shoot at anyone who entered the tomb entered.’

Above (left) an image of Qin Shi Huang, the ruthless first emperor of China, dated to around 1850 AD, and (right) an exhibition of artefacts from the first Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang and terracotta warriors at the Liverpool World Museum, Merseyside in The United Kingdom

Associate Professor Ming Tak Ted Hui at the University of Oxford said he is confident archaeologists will one day uncover the tomb’s deepest secrets, and he is pleased to see increased interest thanks to the Netflix original.

“At a time when we have serious doubts about the truth,” the “heroes” of this story, he says, are the people who gave their lives in the present to better understand the past.

“You will find common interests or common mysteries in it,” he said.

‘It’s not about what culture you belong to (…) it’s not just a project that would attract audiences from China. It attracts audiences worldwide to reflect on what humanity as a whole has achieved.”