Is this why we outlived Neanderthals? Human children had prolonged support from their parents – while Neanderthal kids were left to fend for themselves, study claims

- A study of teeth shows that humans provided long-term child care to their offspring

- This could also be one of the reasons why the Neanderthals eventually became extinct

We once lived among Neanderthals, but they disappeared about 40,000 years ago.

The reasons for their demise vary, but experts have suggested that interbreeding, climate change and violent clashes with humans may be the cause.

Now, a new study of teeth indicates that humans provided long-term child care to their offspring, while young Neanderthals may have achieved independence earlier.

And this could also be one of the reasons why the Neanderthals eventually became extinct, according to experts.

Experts say that Neanderthal children, who lived between 400,000 and 40,000 years ago, and modern human children who lived during the Upper Paleolithic – between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago – may have faced similar levels of childhood stress, but in different stages of development.

We once lived among Neanderthals, but they disappeared about 40,000 years ago. The reasons for their demise vary, but experts have suggested that interbreeding, climate change and violent collisions with humans may be the cause (stock image)

The team from the University of Tübingen in Germany suggests that these findings could reflect differences in childcare and other behavioral strategies between the two species.

They analyzed the tooth enamel of 423 Neanderthal teeth and 444 Upper Paleolithic human teeth.

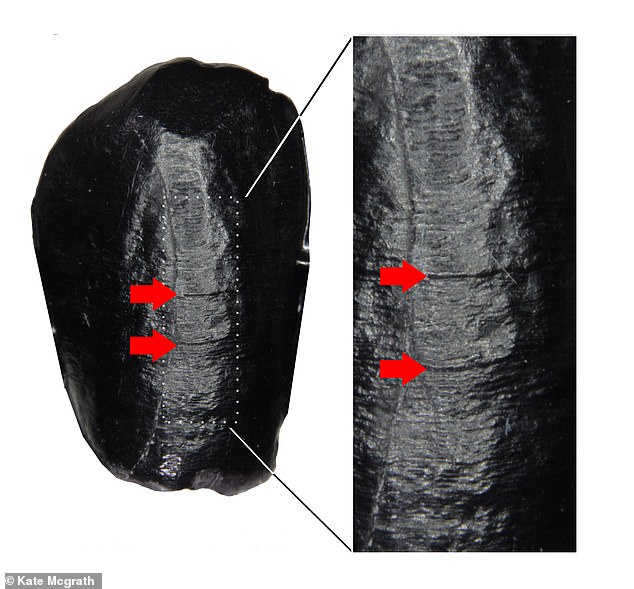

Horizontal grooves of thinning enamel in the teeth indicated early life stress, which previous research has shown can be linked to childhood stressors such as illness, infections, malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies and trauma.

The authors found that the overall likelihood of enamel defects was similar in modern human teeth from both Neanderthal and Paleolithic times, but that the developmental stages at which these defects were likely to occur varied between the two species.

In Upper Paleolithic humans, enamel defects were more common around the estimated age of weaning – between the ages of one and three.

A new study of teeth indicates that humans provided long-term childcare for their offspring, while young Neanderthals may have achieved independence earlier

However, Neanderthals were more likely to have enamel defects peaking after the weaning period, suggesting they were more likely to experience malnutrition during this period.

The authors believe that the stress experienced by Paleolithic human children during weaning could have been caused by increasing energy requirements.

They propose that Paleolithic humans may have helped reduce developmental stress in children after weaning through strategies such as encouraging long-term dependence on parents, exploiting resources more efficiently, and providing children with access to food.

These strategies may not have been used by Neanderthals, they said, which could have contributed to long-term survival advantages for modern humans compared to Neanderthals.

In the journal Scientific Reports, they write that humans may have been better at “mitigating stress in newly weaned children.”

Meanwhile, for Neanderthals, the period shortly after weaning coincides with the “most stressful childhood phase.”

Study author Laura Limmer said: ‘We suggest that modern Upper Paleolithic humans and Neanderthals had different childcare strategies after weaning, with that of the modern Upper Paleolithic humans resulting in better stress reduction in later childhood.

‘These strategies may not only involve support from their parents, but may also be related to other social factors.

“We might say that Neanderthal children became independent earlier or were treated more like adults at a younger age than modern human children.”