Navy SEAL’s chilling suicide note he taped to his door before taking himself in his heart to preserve his brain – as bombshell study reveals chilling pattern on the brains of vets who committed suicide

A Navy SEAL’s chilling suicide note has been revealed five years after he shot himself in the heart to save his brain.

Lieutenant David Metcalf took his own life in a garage at his North Carolina home in 2019, with a stack of books on brain injuries next to him. reports the New York Times.

He also posted a note on the door, which read in part: ‘Memory gaps, lack of recognition, mood swings, headaches, impulsiveness, fatigue, anxiety and paranoia were not who I was, but became who I am.

“Everything is getting worse,” the 42-year-old wrote before shooting himself in the heart and sending his brain to the Defense Department for analysis. Since then, the Defense Department has discovered an unusual pattern of damage, which it suspects was caused by his own weapons.

Now Metcalf’s wife Jamie says she sees his sudden death as a way to draw attention to the problem facing Special Operators.

“He left a conscious message because he knew things had to change,” she told the Times.

Lieutenant David Metcalf took his own life in the garage of his North Carolina home in 2019, leaving behind a note describing the brain problems he was dealing with

At least a dozen Navy SEALS have committed suicide in the past decade, either while in service or shortly after leaving the military.

An investigation into their deaths has since revealed that they all had a number of factors in common.

The average age of the deceased veterans is 43. They all served multiple tours in combat, but none were injured by enemy fire, the Times reported.

All veterans have spent years firing high-powered weapons, jumping out of planes, blowing open doors with explosives, diving deep underwater and learning hand-to-hand combat.

By age 40, almost all of them began to struggle with insomnia, headaches, memory and coordination problems, depression, confusion and sometimes anger.

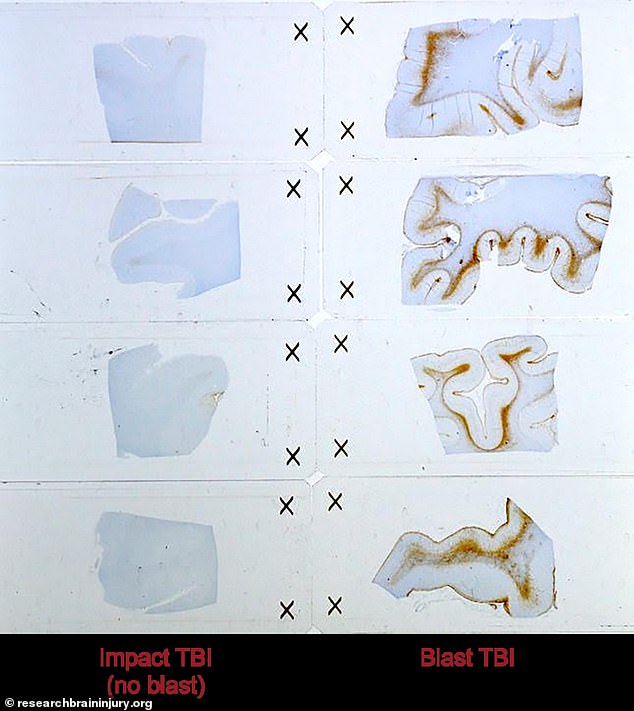

Many were also diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, but a Ministry of Defence study of eight soldiers found that all had brain damage from explosions.

At least a dozen Navy SEALS have died by suicide in the past decade — either while serving in the military or shortly after leaving

It is believed that many suffered brain damage caused by shock waves created by the troops’ own weapons

That brain damage apparently resulted from shock waves caused by the troops’ own triggers in a range of weapons, studies suggest.

The energy waves from a weapon explosion flow through the brain and bounce off tissue boundaries like an echo, the Times said.

Dr. Daniel Daneshvar said the effects may become worse over time with repeated exposure

For a few fractions of a millisecond, these waves create a vacuum, causing the fluid in the nearby brain to explode into bubbles of vapor.

These explosions are then powerful enough to blow apart brain cells.

According to Dr. Daniel Daneshvar, chief of the division of brain injury rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School, there may be no noticeable symptoms at first, but as exposure continues, the effects can become worse.

He explained that the brain can often compensate for the damage, until the injuries build to a critical point where “people fall off a cliff.”

“People may be getting hurt without even realizing it,” Daneshvar said.

“But over time it can add up.”

Petty Officer David Collins committed suicide in March 2014

For Petty Officer David Collins, the repeated exposure led to confusion in the years before he committed suicide.

Collins had spent 20 years as a Navy SEAL and deployed twice to Afghanistan and three times to Iraq.

When he wasn’t deployed, his wife said he spent hundreds of days away from home each year training.

The fight never seemed to faze him, his wife Jennifer said, but toward the end of his career, Collins began avoiding social gatherings, had difficulty falling asleep and began creating obsessive family schedules — becoming irritated when they weren’t were followed.

Simple chores like raking the leaves began to confuse him, Jennifer said, describing how we would walk out the door to go to work, realize he had forgotten his keys, go back inside to get them and forgot why he came back.

His mental health then really started to take a turn for the worse at age 45.

He left the Navy and went to work as a civilian, teaching soldiers how to operate small drones. But one morning, Jennifer called her in a panic after he had been away on a business trip. He said he had forgotten how to do his job and hadn’t slept in four days.

“He was super anxious, almost paranoid,” she said. “He was nothing like my husband.”

His wife, Jennifer, was adamant about donating his brain to research and has encouraged other Special Operations families to do the same

At the time, the military typically associated brain injuries with the detonation of roadside bombs, but Collins never experienced that.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Collins with depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, and prescribed a number of medications that did not help.

Collins would subsequently take his own life in March 2014.

When police arrived at their Virginia Beach home to confirm his death, Jennifer said she was “adamant” that she wanted his brain donated for research.

“I wanted to try to find answers,” she said.

That donation was the first for the Department of Defense Brain Tissue Repository in Bethesda, Maryland, which had been established two years earlier to examine the brains of deceased veterans for evidence of PTSD and traumatic brain injury.

As researchers there studied Collins’ brain, they noticed that almost everywhere where tissues of different density or stiffness met, there was a rim of scar tissue.

“For the first time, we could actually see the injury,” said Dr. Daniel Perl. “Once you know what the problem is, you can start designing solutions.”

The Pentagon says it has a ‘moral obligation to protect the cognitive health and combat effectiveness of our teammates’

They later discovered the same pattern in six of the eight Navy SEALs who committed suicide, as Jennifer convinced more and more families to come forward.

By the time Metcalf died in 2019, brain donations had become somewhat common for Special Operations troops.

So after the lieutenant died, Jamie decided to donate his brain to research as well.

She described how she noticed her husband’s condition suddenly deteriorate when he returned from his fifth deployment in 2018.

He was a top performer, an enlisted SEAL sniper, and taught martial arts to other SEALs. A few years before he died, Metcalf also decided to pursue a military medical career, becoming an officer and entering a training program for physician assistants.

But he became increasingly confused and suffered from headaches, Jamie says. He described putting wet laundry in the dryer on top of dry clothes.

“It was so different from him; he had always been so organized,” she said.

“Now I know he was afraid something was happening in his brain, but I think he was trying to hide it at the time.”

However, researchers determined that Metcalf and another soldier had a different type of damage in the same brain region as the other SEALs.

Star-shaped accessory cells in their brains, called astrocytes, were found to be repeatedly damaged and grew into large, tangle-like masses that barely functioned.

According to the Times, a study on astrocytes is coming soon.

Meanwhile, Rear Adm. Keith Davids, commander of Navy Special Warfare — which includes the SEALs — said, “We have a moral obligation to protect the cognitive health and fighting ability of our teammates.”

He said the Navy tries to reduce brain injuries “by limiting exposure to blasts and actively participating in medical research designed to advance understanding in this important field.”