National Maritime Museum declares failure to reflect the ‘legacies of slavery’

>

The National Maritime Museum has been accused of ‘erasing’ British history after declaring that one of its galleries does not reflect the ‘legacies’ of slavery or ‘black voices’.

The south London-based institution’s ‘Atlantic Gallery’ opened in 2007 and focuses on the role the ocean has played as a route for the movement of goods, people and ideas over the centuries.

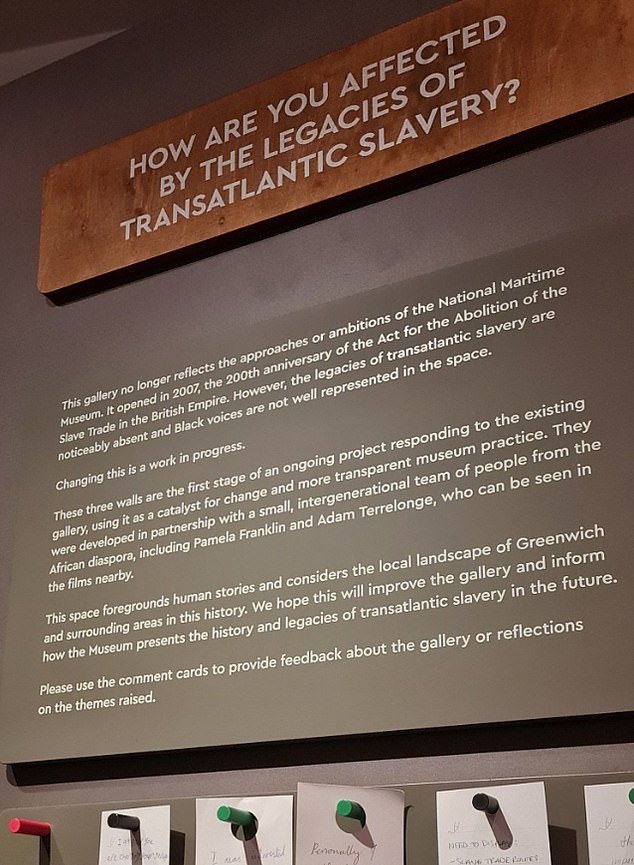

But a recent exhibit installed at the gallery now tells visitors that it “no longer reflects the approaches or ambitions of the National Maritime Museum” because the “legacies of transatlantic slavery are conspicuously absent and black voices are not well represented in the space”.

Visitors are invited to post their comments on pieces of paper in the gallery, under a banner that reads: ‘How do the legacies of transatlantic slavery affect you?’

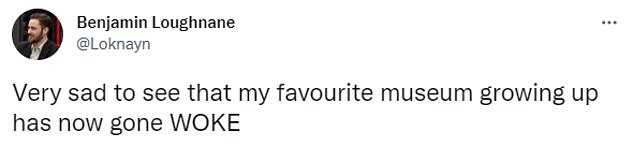

But writer Benjamin Loughnane, who visited the museum earlier this month, said he was “so sad” to see his “favorite museum” had “woken up”.

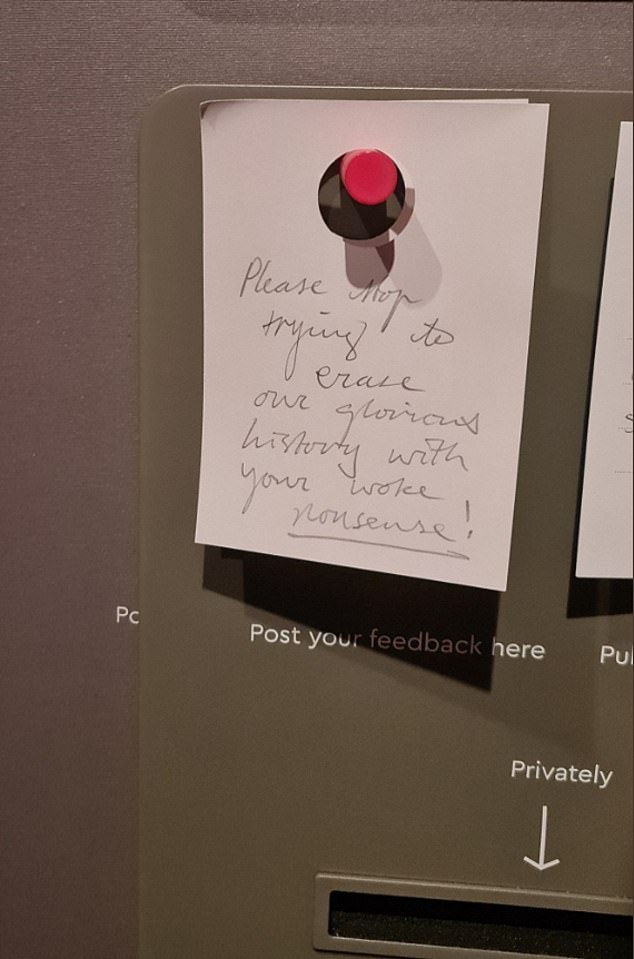

Posting his comments to the gallery, he wrote in a note: “Please stop trying to erase our glorious history with your awakening nonsense!”

The National Maritime Museum has come under fire after discrediting one of its own galleries because the ‘legacies’ of slavery are ‘absent’ from it. The Atlantic Gallery, which opened in 2007, displays a message to visitors saying it “no longer reflects the approaches or ambitions of the National Maritime Museum” because “the legacies of transatlantic slavery are conspicuously absent and the voices black are not well represented in space’

In response to an online critic who asked him “what was so glorious about the slave trade”, he noted that Britain was one of the first countries to abolish the practice.

The message in the Atlantic Gallery tells how it was inaugurated in the year of the 200th anniversary of the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

He goes on to explain that three new walls, some of which contain messages from visitors, are “the first stage of an ongoing project that responds to the existing gallery.”

The walls were developed with the help of a “small intergenerational team of people from the African diaspora,” he adds.

The message continues: ‘This space highlights human stories and considers the local landscape of Greenwich and its surroundings in this story.

“We hope this will enhance the gallery and inform how the Museum presents the history and legacies of transatlantic slavery in the future.”

Writer Benjamin Loughnane, who visited the museum earlier this month, said he was “so sad” to see his “favorite museum” had “woken up”. Posting his comments to the gallery, he wrote in a note: “Please stop trying to erase our glorious history with your awakening nonsense!”

As recently as July of last year, information about the gallery on the museum’s website did not display a message disparaging the existing space.

But in November last year, a message similar to the one in the physical gallery was added.

The updated page adds that, to mark International Slavery Remembrance Day in 2021, five young men were invited to ‘interrogate’ the gallery.

A text written by the participants on a separate page reads: ‘The Atlantic Worlds gallery needs to be reimagined.

‘The hard truths of the period between the 17th and 19th centuries, the rise of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, are difficult to confront.

“But the stories of the lives affected by these global systems and their lasting impact today must be told.”

‘This project is one small step towards this: an opportunity to broaden the perspectives contained within the gallery.

‘It is impossible to transform space in one day, but we hope to create a space for practical conversations that shift power away from the institution and into the hands of people affected by the legacy of slavery, empire and racism that persists today. ‘

The young people made a series of changes to the gallery, including changing the lighting to make it brighter, because ‘it’s not a place to fall asleep, but to wake up and face reality’.

The message in the museum’s gallery comes after the museum removed a bust of King George III showing him flanked by two kneeling African men because it was a “hurtful reinforcement of racial stereotypes”.

The institution said in 2021 that the figurehead, believed to have been created to celebrate Britain’s victory at the Battle of Waterloo, came under “frequent criticism” and was “a hurtful reinforcement of stereotypes”.

Mr Loughnane took to Twitter to criticize the museum, saying it had “woken up”.

And in October 2020, the museum said it would review Lord Horatio Nelson’s legacy as part of its efforts to challenge Britain’s ‘barbaric history of race and colonialism’.

The museum in Greenwich, London, holds the hero admiral’s love letters and the coat he wore when he was killed during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

There have been a number of other ‘wake up’ movements by Britain’s cultural institutions.

Tate Britain’s exhibition on painter William Hogarth that opened in 2021 was criticized after curators highlighted “sexual violence, anti-Semitism and racism” in the painter’s works.

And National Gallery staff conducted a three-year audit that linked hundreds of his famous paintings to slavery.

In April last year, the Courtauld Gallery came under fire for introducing a new label on its paintings, including Édouard Manet’s 1882 work A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The work shows a waitress at the famous Parisian cabaret club looking out at the viewer and a male customer who can be seen in a mirror image behind her.

The new information panel, both in the gallery and online, indicated that the “enigmatic expression of the female subject is disturbing, especially as she appears to be interacting with a male patron.”

Critics called it a “witty attempt to denounce misogyny” that “inadvertently focuses the male gaze” by shifting the viewer’s attention to the man.

The National Trust has also been criticized for a report in 2021 detailing links between 93 of its holdings and slavery and colonialism.

Winston Churchill’s former home, Chartwell, in Kent, was among the properties on the list because the wartime prime minister served as secretary of state for the Colonies.

The National Maritime Museum (pictured) is part of the Royal Museums, Greenwich

The move sparked a fierce reaction from some quarters, including some MPs and peers, and the trust faced accusations of ‘wake-up’ and jumping on the Black Lives Matter bandwagon.

Following the complaints, the charity regulator opened a case to examine critics’ concerns, but concluded that the National Trust had acted in accordance with its charitable purposes and that there was no reason to take regulatory action against it.

A spokesman for the National Maritime Museum said: “The Atlantic Worlds gallery opened in 2007. The galleries are regularly updated with new exhibits and stories.

In October 2020, the museum said it would review Lord Horatio Nelson’s legacy as part of its efforts to challenge Britain’s ‘barbaric history of race and colonialism’. Pictured: Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London

The “Work in Progress” exhibit, which invites visitors to provide feedback on the existing gallery, was designed in 2019 for a March 2020 launch, but was delayed due to the pandemic and installed when the Museum reopened (after of the zipper closures) .

‘We are continually learning more about the transatlantic slave trade and its legacies, as well as other aspects of history relating to the Royal Museum Greenwich sites, themes and collections.

“Some of this history had not been researched when the gallery opened fifteen years ago and the Museum is in ongoing conversations with a variety of stakeholders, scholars and visitors, looking at how we present a better understanding of this history with updating and new research. ‘