Mystery of why more than 2,000 gray whales have died along US coast since the 1980s may have been SOLVED – and the reason is haunting

>

More than 2,000 gray whales have died off the Pacific coast, coinciding with three unexplained mass die-offs, and scientists now think they know why.

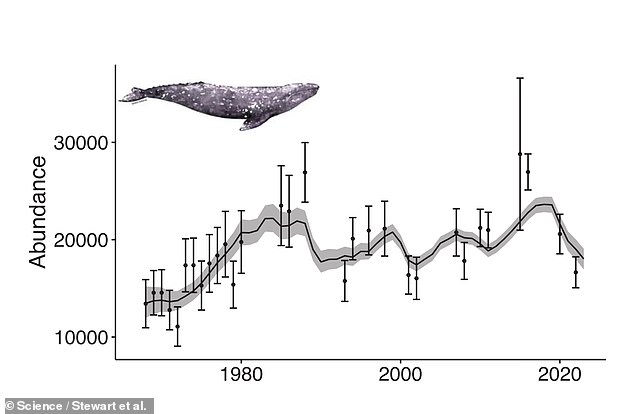

In 1986, gray whale numbers made an impressive comeback from the brink of extinction, after the International Whaling Commission issued a blanket ban on commercial whaling.

But researchers have since tracked a series of new, more mysterious mass deaths of the majestic marine mammals — including an ongoing wave that their research has linked to climate change.

For decades, marine researchers had speculated that the deaths were a natural consequence of the post-ban gray whale population boom, as their growing numbers found a new balance within the North Pacific food chain.

Now, new research has found evidence that recent “unusual mortality events” may actually be the result of shrinking Arctic ice, leading to a dwindling supply of whales’ favorite food: coastal crustaceans, such as shrimp and scud.

In fact, these thousands of gray whales appear to have starved to death as their ecosystem disappeared beneath them.

There have been three unusual and puzzling mass die-offs since gray whale populations rebounded in the mid-1980s. The first occurred between 1987 and 1989, killing at least 700 gray whales. The second incident occurred between 1999 and 2000, and the death toll reached 651 people.

Even more troubling for researchers is the more recent and longer mass die-off event, which began in 2019 and is still ongoing: 688 whales have died and counting. Above, scientists and volunteers dissect one of these beached gray whales on April 23, 2019 in California.

Marine researchers were able to track and find trends in gray whale mortality, using data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service, which has maintained the US Marine Mammal Strandings database since 1990.

“These are extreme population fluctuations that we did not expect to see in a large, long-lived species like gray whales,” said marine ecologist Joshua Stewart, who led this investigation into the unexplained deaths of whales.

Stewart and his team focused on three unusual and puzzling mass die-offs that have occurred since gray whale populations began to return to normal in the mid-1980s.

The first wave occurred between 1987 and 1989, killing at least 700 gray whales.Eschrichtius robustus) At a time when scientists’ ability to track every beached whale or its stranding was limited.

Researchers were better able to track and find trends in gray whale mortality collected since 1990 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) U.S. Marine Mammal Database.

When the second mass die-off occurred between 1999 and 2000, the event came with a more precise death toll of 651 whales.

These deaths caused gray whale populations to decline by 15 to 25 percent each time, according to the new study published Thursday in the journal. Sciences.

But even more troubling for researchers is the more recent and longer mass die-off event, which began in 2019 and is still ongoing until September 26, 2023: 688 whales have died and counting.

Within a span of six months in 2019, about 70 gray whales were found dead, prompting widespread concern and necropsies on a California beachfront by experts at the California Academy of Sciences and volunteers.

“We are now in uncharted territory,” Stewart, the study’s lead author, said in a university press release. “The previous two events, although important and dramatic, only lasted a few years.”

He added: “The recent death rate has slowed and there are signs that things are starting to improve, but the population has continued to decline.”

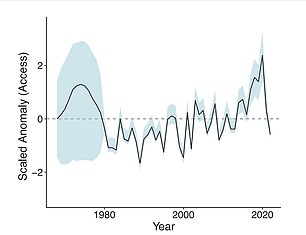

Stewart’s team found that the first two die-offs were closely linked to seasonal growth of Arctic sea ice, preventing then-burgeoning whale populations from accessing seasonal feeding grounds.

But researchers have discovered a new cause for the longer die-off event that began in 2019: melting Arctic sea ice, cutting off the food chain that gray whales depend on.

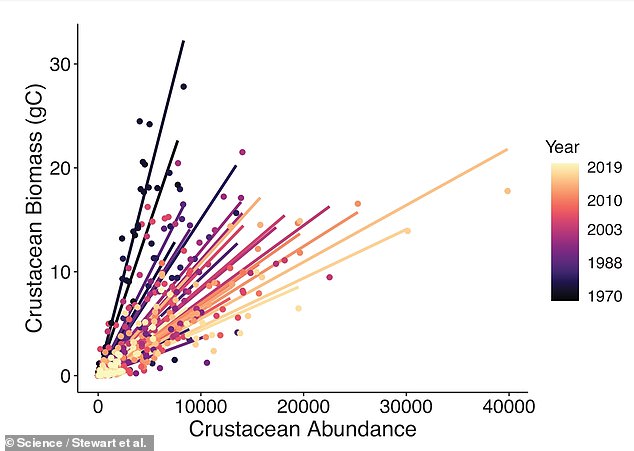

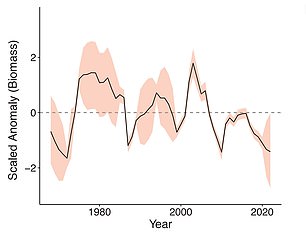

Shrinking Arctic ice has led to the loss of green algae that grows on its undersea surface, which in turn has led to a decline in the population of gray whales’ main food: coastal crustaceans such as shrimp and scud. The study found a decline in crustacean biomass in North Pacific waters

Researchers were able to map the timing of the disappearance of Arctic sea ice (left), recorded by NOAA’s National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), as crustacean populations declined (right). To show the crustacean’s decline, the researchers took data and weighed specimens caught from 1970 to the present, using those weights to measure the overall health of the species.

First, the shrinking ice has led to the loss of green algae that grows on its face under the sea’s surface, which in turn has led to smaller, less healthy populations of the gray whales’ main food, coastal crustaceans such as shrimp and scud.

Researchers were able to map the timing of the disappearance of Arctic sea ice, recorded by NOAA’s National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), as crustacean populations declined.

To show the decline of crustaceans, the researchers took data and weighed samples of wild-caught crustaceans from 1970 to the present, using the weights of each of these shellfish, per individual, as a measure of the overall health of the species.

“All of these factors are converging to reduce the quality and availability of the food they depend on,” Stewart said.

At the peak of the whale comeback, the species numbered about 25,000 gray whales, but due to deaths and low birth rates, researchers said the population is now at 14,500 whales and drowning.

“A dramatically warmed Arctic Ocean may not be able to support 25,000 gray whales as was the case in the recent past,” says Stewart.

However, marine research sees a glimmer of hope in the long evolutionary history and intelligence of gray whales as a species.

These marine mammals have survived and adapted over hundreds of thousands of years of world history, overcoming ice ages and other environmental disruptions, meaning the risk of complete extinction is fairly low.

“I can’t say there’s a risk of gray whales being lost to climate change,” Stewart said.

“But we need to think critically about what these changes might mean in the future.”

(tags for translation)dailymail