My Teacher The Abuser: Fighting For Justice review – I was left seething this predator will never face proper justice, writes CHRISTOPHER STEVENS

My Teacher, the Abuser: Fighting for Justice (BBC1)

The Art of Filmmaking with Ian Nathan (Sky Arts)

The sad thing is that justice can never really be done. The sexual predators whose abuses went unchecked in British schools in the 1970s and earlier are all now dead or ancient.

Television and radio presenter Nicky Campbell and a group of his former Edinburgh Academy classmates have worked steadfastly to expose the crimes of an evil man, a former maths teacher called Iain Wares.

But the shambling figure seen in the Panorama special My Teacher The Abuser: Fighting For Justice is no longer the monster that tormented generations of students. He stumbled into court in South Africa, where he now lives, looking like a poisonous, wizened gremlin without an ounce of remorse. He knew that no matter what punishment awaited him, he could get away with perverted attacks on children throughout his career.

For Campbell and his friends, now men approaching retirement age, the frustration is not just that Wares was enabled by the Edinburgh Academy and later at Fettes College to harass boys without restraint.

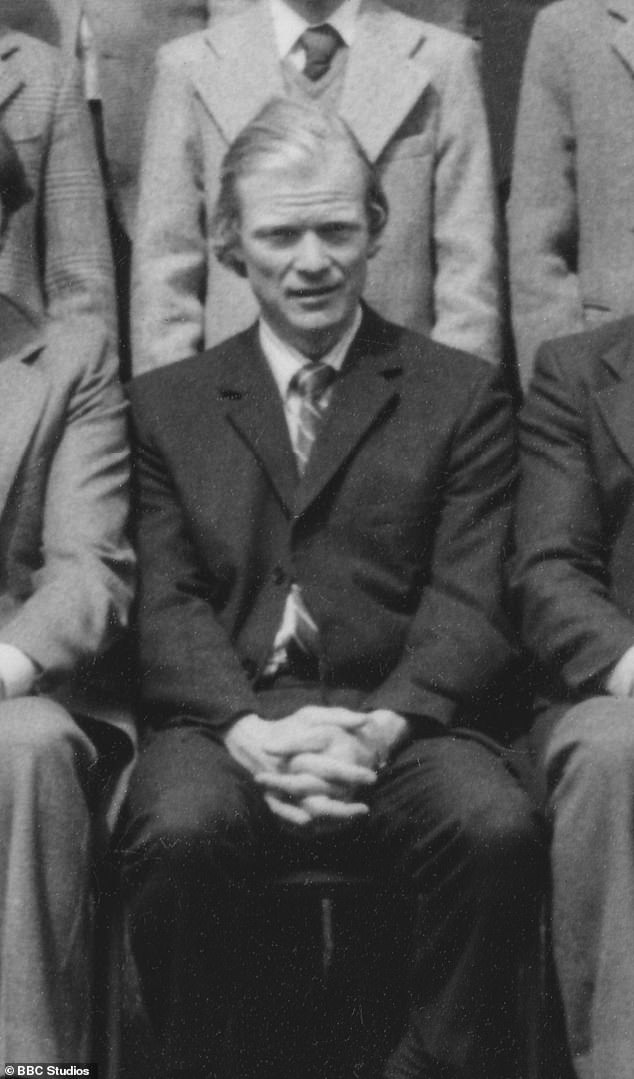

Television and radio presenter Nicky Campbell (pictured) and a group of his old classmates from Edinburgh Academy have worked steadfastly to expose the crimes of an evil man, a former maths teacher called Iain Wares.

For Campbell and his friends, now men approaching retirement age, the frustration is not just that Wares was enabled by the Edinburgh Academy and later Fettes College to harass boys without restraint (photo: Iain Wares)

It's also that he can safely admit his behavior while minimizing or dismissing its importance – and he always has. Incredibly, the report found, when he first came to Britain in the 1960s, he had already been charged with sex crimes and had undergone psychiatric treatment on arrival in Scotland.

Yet he was able to work as a teacher at a preparatory boys' boarding school. Worse still, when a series of parental complaints forced him to leave, he was given a glowing reference.

Campbell said Wares' predatory behavior was always common knowledge among teaching staff – which he called “really bad men, horrible, disgusting men who did horrible things.”

But this documentary failed to spread the blame or accuse multiple teachers. The focus was on Wares and a teacher at Fettes, Hamish Dawson, who died in 2009 without ever facing disciplinary or legal action.

As a former student at a 1970s boys' day school, I understand all too well the struggle to survive in an atmosphere of distorted normality – how nicknames for teachers, for example, helped children instinctively know which teachers were prone to lashing out with knuckles, canes and boarddusters. Some were drunks, some were curb crawlers, others walked through the locker rooms and showers throwing a wet towel.

However, 'Weirdo Wares' does not capture the full horror of the maths lessons at Edinburgh Academy, where boys were brought to the front of the class to be abused. Many of the testimonies of the men who fought back tears are too moving and disturbing to repeat here.

Film critic Ian Nathan's series The Art Of Film concluded with a retrospective of biopics, dramas loosely based on real lives, from Queen Victoria to Charlie Chaplin and Howard Hughes

Like a stick stirring up mud in a stagnant pond, all this brought a lot of old mud to the surface. After the hour was up, I took the dog for a long, freezing walk, seething with anger because it was now too late for real justice.

Judging history is much easier when it comes to celluloid. Film critic Ian Nathan's series The Art Of Film concluded with a retrospective of biopics loosely based on real lives, from Queen Victoria to Charlie Chaplin and Howard Hughes.

Contributions from fellow critics and from filmmakers such as Stephen Woolley and Paul Webster shed light on the narrative techniques of biographical films. But the real fun of this show lies in the well-chosen segments.

This time we saw fragments of Greta Garbo's Queen Christina, and even a glimpse of Georges Melies' Joan of Arc from 1900. That's film history.