My kidney stones almost killed me after a rare complication led to sepsis

A woman developed near-fatal sepsis after suffering from a rare form of kidney stones, which has only been documented twelve times.

The 63-year-old from Tennessee sought medical attention after noticing blood in her urine while being treated for a urinary tract infection.

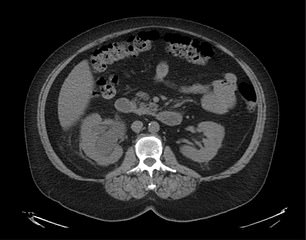

A CT scan revealed multiple stones around her right kidney that were clogging her urinary tract.

Although kidney stones are common and affect one in ten Americans, doctors discovered that these stones were filled with gas that had formed in the urinary tract, a rare complication.

Doctors think this is caused by bacteria, which are also a cause of urinary tract infections. Only twelve cases have ever been reported in the medical literature.

The woman underwent lithotripsy, a procedure that uses shock waves to break up stones, which are made of calcium crystals that form in the urinary tract, so they can pass through the urine.

But two days later she returned to the emergency room complaining that she “just didn’t feel well.”

Her doctors believe the lithotripsy caused her to spiral into sepsis, a life-threatening overreaction to an infection that causes the immune system to attack healthy organs and tissues.

If left untreated, sepsis can lead to tissue death, multiorgan failure, and death.

An unnamed woman in Tennessee developed sepsis after her urinary tract caused a rare form of kidney stones (stock image)

The above scans show imaging tests before and after the woman had a procedure to break up her kidney stones. The gas-filled stones can be seen in the left image, but they are no longer present in the right image

Doctors who treated the unnamed woman, from the University of Tennessee Medical Center-Knoxville, wrote in a medical journal she had a history of several chronic conditions.

These include diabetes and Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disease that causes the thyroid gland to produce too much thyroid hormone.

Both conditions can increase the risk of urinary tract infections.

In diabetics, high levels of glucose in the urine can create an environment where harmful bacteria can gather.

Excessive production of thyroid hormone due to Graves’ disease can also cause frequent urination and difficulty emptying the bladder, increasing the risk of urinary tract infections.

Urinary tract infections produce enzymes that make the urine less acidic, and these enzymes form into kidney stones.

The woman tested positive for ‘a strong growth’ of the bacterium Proteus mirabilis, which has been shown to cause urinary tract infections.

The doctors said this bacteria could have led to excess gases such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen in the kidneys, allowing the kidney stones to fill, a phenomenon so rare that “only twelve cases are described.”

The patient fell into sepsis two days after the lithotripsy ruptured her kidney stones. It is unclear how the procedure caused this, but it is possible that it is due to the bacteria still in her body.

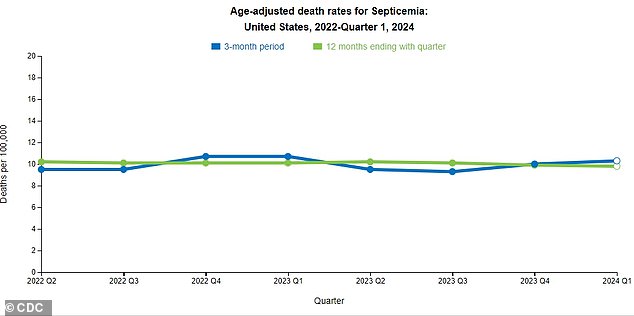

The latest sepsis data from the CDC shows a slight increase in sepsis deaths over the past three months. Experts warn this could be due to a lack of a coherent sepsis strategy in the US.

Sepsis has been called a “silent killer” and is responsible for 350,000 American deaths per year, or one every 90 seconds.

Only heart disease and cancer result in more deaths, killing 700,000 and 600,000 Americans respectively.

Across the world, sepsis is responsible for one in five deaths (20 per minute) and outnumbers cancer.

But despite how frighteningly common the condition has become, one in three Americans have never heard of it, the charity Sepsis Alliance found.

The woman’s prognosis and treatment are unclear, but sepsis is usually treated with antibiotics for the underlying infection and medications called vasopressors that divert blood flow back to vital organs.

However, this requires blood from ‘non-vital’ areas such as limbs, leading to tissue death and amputations.