Multiple former senior Boeing staffers – one of whom also worked for FAA – say they would NOT fly on killer 737 Max planes and that they’re urging their families to avoid them too

Two former senior Boeing employees have said they would not fly the company’s killer 737 Max after the latest safety fiasco – and one said he urged his family not to set foot on one either.

“There’s no way I would fly a Max plane,” said Ed Pierson, a former Boeing senior manager told the LA Timesfollowing the Jan. 5 incident in which a door plug from an Alaska Airlines 737 Max 9 blew into the air.

“I worked at the factory where they were built, and I saw the pressure that workers faced to get the planes out the door,” he explained.

Adding: ‘I tried to disable them before the first crash.’

Returning the Max 9 to service was “yet another example of poor decision-making and endangers public safety,” Pierson told the publication.

Former Boeing senior manager Ed Pierson would ‘absolutely not fly a Max plane’

Joe Jacobsen, a former engineer at Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration, expressed concerns about the planes returning to the skies too quickly and said he would urge his family not to set foot aboard a Boeing 737 Max to put.

Joe Jacobsen, a former engineer at Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration, agreed, telling The Times it was “premature” to return the jets to the air.

“Rather than solving one problem at a time and then waiting for the next one, solve them all,” says Jacobsen.

‘I would tell my family to avoid the Max. “I would really tell anyone,” he said.

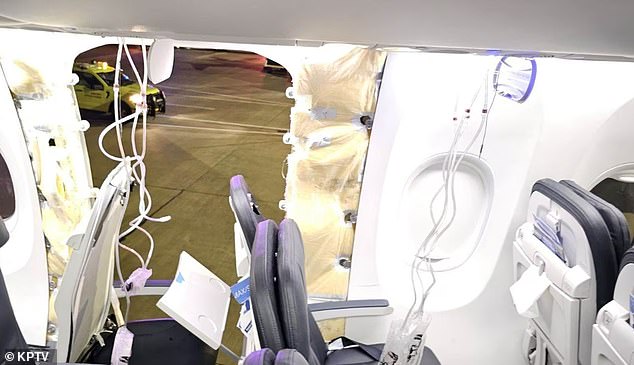

A faulty door plug disconnect caused a panel to come loose at 5,000 feet of a Max 9 aircraft on an Alaska Airlines flight on January 5.

The Max 9s were temporarily grounded by aviation regulators pending safety checks, but are now back in the air.

A photo shows the blown out window. It is offered as a door on the plane. Alaska chose not to take this option – even though the frame of the future door was completely torn out due to the hull failure

Alaska Flight 1282 was leaving Portland just after 5 p.m. local time on Friday when a window blew out at 16,000 feet, ripping a child’s shirt

Other versions of Boeing’s Max have also been at the center of safety scandals, including the Max 8, which had two crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed 346 people.

The plane’s computer system was to blame, with Boeing accused of fitting oversized engines to a 60-year-old airframe and then trying to use software to fix that imbalance.

“Our long-term focus is on improving our quality so we can regain the trust of our customers, our regulator and the flying public,” Stan Deal, CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, wrote in a message to employees on Friday evening.

Adding: “Frankly, we have disappointed and let them down.”

Jennifer Homendy of the National Transportation Safety Board said the impact at 16,000 feet was an “accident, not an incident.”

The Boeing 737-9 MAX rolled off the assembly line just two months ago and received certification in November 2023, according to the FAA record posted online

“Each of our 737-9 MAX aircraft will not return to service until rigorous inspections are completed and each aircraft is deemed airworthy under FAA requirements,” Alaska Airlines said in a statement.

“Let me be clear: This will not be business as usual for Boeing,” FAA Administrator Mike Whitaker said in a statement last week.

“The quality assurance issues we’ve seen are unacceptable,” Whitaker said. “Therefore, we will have more people on site to closely monitor and monitor production and production activities.”

The FAA also noted that it would not allow Boeing to expand production of its Max fleet, including the 737 Max 9.

Just weeks before the Alaska Airlines incident, Boeing asked the FAA to exempt the latest variant of its 737 Max aircraft from safety inspections, despite the risk of engine failure.

FAA officials said Boeing was working to resolve the hazard that could cause the engine casing to overheat and break off during flight, the Associated Press reported.

In the meantime, federal officials told pilots flying the 737 Max 7, which is not yet used by airlines, to limit the use of an anti-icing system in some circumstances to prevent damage that “could lead to loss of control of the aircraft.’

Boeing unveiled their 737 Max 9 in 2015 and since its approval by the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) in 2017, it has become one of the most widely used aircraft in the world.

Wreckage of Syrian Airlines Boeing 737-MAX aircraft is seen on March 11, 2019

But it has a deeply troubled reputation and plunged Boeing into the biggest crisis in the history of the Chicago-headquartered company.

A year after the plane entered service, it crashed for the first time: in October 2018, a 737 Max operated by the Indonesian airline Lion Air crashed shortly after takeoff, killing all 189 people on board.

Five months later, in March 2019, a second 737 Max operated by Ethiopian Airlines crashed again shortly after takeoff, killing all 157 people on board.

Three days later the planes were grounded by the FAA.

It later emerged that in internal messages, Boeing staff were more cavalier about FAA rules and critical of the Max’s design – particularly a computer system responsible for both fatal crashes.

One of them said the plane was “designed by clowns who are in turn supervised by monkeys.”

The 737’s design dates back to the 1960s, and Boeing was criticized for adding large engines to an old airframe instead of using a clean sheet design.