Moving moment: six deaf children can hear for the first time thanks to groundbreaking gene therapy

Thanks to a groundbreaking treatment, six deaf children aged one to eleven years old have been able to hear the world for the first time.

The children were part of two experimental groups in China and the US, all of whom were born with a gene mutation that blocked the production of a protein needed for hearing.

Scientists injected a version of the gene called otoferlin (OTOF) into the inner ear and the cells started producing the missing protein.

The children’s hearing levels are now up to 70 percent normal after 26 weeks of treatment, with progress starting as early as six weeks.

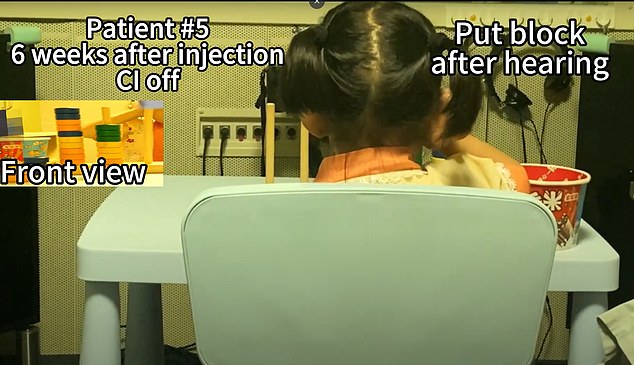

Progress videos show a one-year-old child responding to his name being called for the first time, and another little girl repeating father, mother, grandmother, sister and “I love you” – while previously she could not speak.

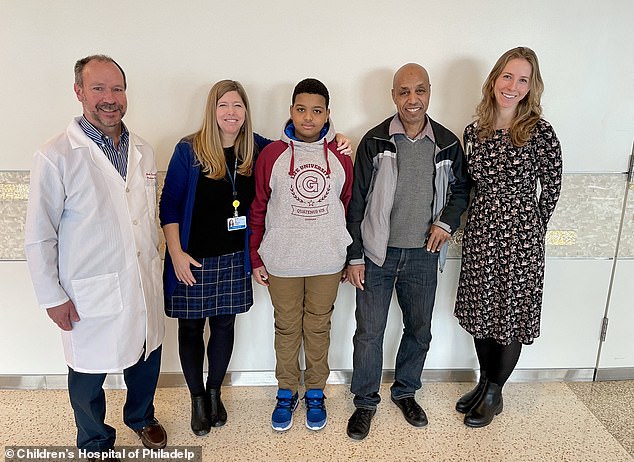

Aissam Dam, 11, heard this for the first time this week after being treated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) – a first in the US.

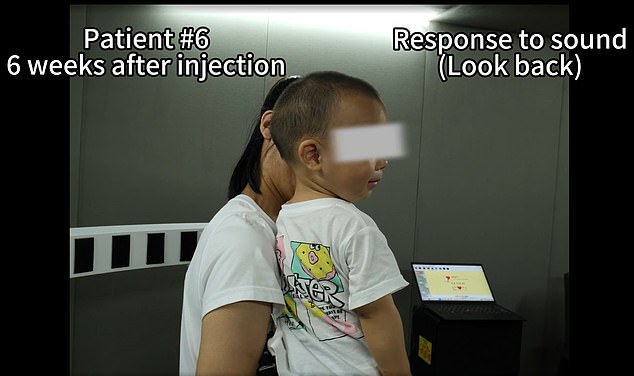

The children were part of two experimental groups in China (pictured) and the US, all of whom were born with a gene mutation that blocked the production of a protein needed for hearing.

Progress videos show a one-year-old child responding to his name for the first time

Zheng-Yi Chen, DPhil, professor at Harvard Medical School and study author for Chinese Experiments, said: ‘If children cannot hear, their brains can develop abnormally without intervention.

‘The results from this study are truly remarkable. We saw children’s hearing improve dramatically week after week, as well as regain their speech.”

Hereditary deafness is the latest condition scientists are targeting with gene therapy, which has already been approved to treat diseases such as sickle cell disease and severe hemophilia.

About 34 million children worldwide suffer from deafness or hearing loss, and genes are responsible for up to 60 percent of cases.

Mother was born ‘profoundly deaf’ due to a very rare defect in his OTOF gene, which was also the case with the five children in China.

A faulty gene prevents the production of otoferlin, a protein needed by the ‘hair cells’ of the inner ear, which convert sound vibrations into chemical signals sent to the brain.

Otoferlin gene defects are rare and responsible for one to eight percent of hearing loss at birth.

Dam underwent a surgical procedure in October that partially lifted his eardrum and then injected a harmless virus, modified to carry working copies of the otopherlin gene, into the internal fluid of his cochlea.

As a result, the hair cells began to produce the missing protein and started functioning properly.

Aissam Dam (center), 11, was heard from for the first time this week after being treated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) – a first in the US

Scientists injected a version of the gene called otoferlin (OTOF) into the inner ear and the cells started producing the missing protein. Dam underwent a surgical procedure in October and was recently able to respond to sounds coming through earplugs (photo).

Nearly four months after receiving the treatment in one ear, Aissam’s hearing has improved: he has only mild to moderate hearing loss.

He is literally hearing sound for the first time in his life, CHOP shared in a statement.

Dr. John A. Germiller, CHOP, said: “Gene therapy for hearing loss is something we, physicians and scientists in the hearing loss world, have been working towards for more than two decades, and now it’s finally happening.

‘Although the gene therapy we performed on our patient was to correct a defect in one very rare gene, these studies may open the door to future use for some of the more than 150 other genes that cause hearing loss in children.’

Dam’s success story came just days after five children in China learned they had received the same treatment.

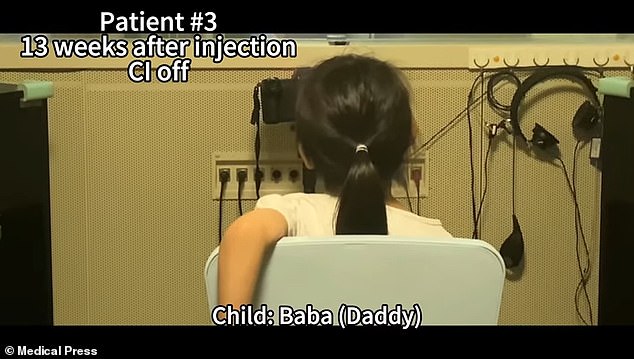

A six-year-old girl nicknamed YiYi could not speak because she was deaf from birth.

A month after the injection, YiYi’s mother, Quin Lixue, said her daughter heard for the first time with the treated ear and repeated what she heard, reports MIT Technology Review.

In a video, Lixue is seen covering her mouth so YiYi couldn’t read her lips and asking her daughter to repeat what she said.

“Clouds blossomed one by one in the mountains,” Lixue said.

An unnamed girl in China said ‘daddy’ for the first time thirteen weeks after treatment

“Clouds, one, one, bloomed in great mountains,” Yiyi replied.

YiYi was part of Fudan University Eye and ENT Hospital in Shanghai, China, where the first patient was treated in December 2022.

The team published their results on January 24 in the journal The Lancet.

Although the therapy did not produce average hearing levels, the children had an auditory response of more than 95 decibels – as loud as a revving motorcycle engine.

A total of six children received the treatment in China, but one child did not see improved hearing due to pre-existing immunity to the type of virus used to deliver the new gene to the cells of the inner ear.

A video shows Lixue covering her mouth so YiYi couldn’t read her lips and asking her daughter to repeat what she said

Another little girl in China responded to sounds after six weeks of treatment

The treatment would have done more harm than good by destroying the child’s immune system.

The five children who received the treatment showed hearing recovery after 26 weeks, with progress beginning after six weeks.

Another demonstration video from the study involved a one-year-old child who was unresponsive to sounds before the injection.

Researchers monitored his progress and showed that after six weeks the child responded to his father’s voice.

And the young boy started talking about two weeks later.

“Since cochlear implants were invented 60 years ago, there has been no effective treatment for deafness,” says Chen. “This is a huge milestone that symbolizes a new era in the fight against all types of hearing loss.”