Most people who think they suffer from anxiety and depression don’t, warns one of Britain’s leading GPs

Thousands of Brits are confusing the ‘normal stresses of life’ with mental health problems – and wrongly diagnosing themselves with psychiatric conditions, one of Britain’s leading GPs has warned.

Professor Dame Clare Gerada, former president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, told MailOnline that Britain has a “problem” with people “looking for labels to explain their concerns”.

Professor Gerada’s concerns echo those of former Prime Minister Sir Tony Blair, who yesterday warned about othe medicalization of the ‘ups and downs of life’.

Sir Tony, who was Prime Minister from 1997 to 2007, said there is a danger that too many people going through life’s normal challenges are being told they are suffering from a mental illness.

“There are people of all different ages who want a diagnosis or a label,” Professor Gerada said.

“They prefer to have a label rather than wonder why their lives could be so challenging, or where things could have gone wrong.”

Professor Gerada’s comments add to a growing chorus of concerns among some of Britain’s top psychiatric professionals, who say self-diagnoses of mental illness are increasing pressure on an already strained NHS.

Dr. Sameer Jauhar, a psychiatrist and senior clinical lecturer at King’s College London, told MailOnline that there was a “major” difference between the symptoms people “self-report” and the medical criteria for diagnosing mental illness.

Professor Dame Clare Gerada, former president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, said Britain has now ‘reached a tipping point’ and people are seeking labels ‘to explain their concerns’

Former Prime Minister Sir Tony Blair yesterday warned against over-medicalising the ‘ups and downs’ of life

“When many people talk about their mental health, they are often describing something that is not what we in the profession call depression,” he said.

‘Clinical depression is not just a low mood. They are motor effects – slowing down someone’s body movements, for example.

‘It can affect your attention, your concentration, your memory. Just saying you have a low mood doesn’t necessarily mean you have depression.

‘When Tony Blair says people self-diagnose, he’s right.’

Professor Carmine Pariante, an expert in biological psychiatry at King’s College London, also warned that greater awareness of mental health problems has led to some “thinking they have an illness rather than just experiencing the difficult levels of stress or anxiety that belong to life’.

He told MailOnline: ‘Many people with significant levels of depression do not seek help, which is a major problem.

‘But in the case of many others, we need to be brave and give people reassurance that what they are experiencing is normal and help them take responsibility for their well-being by doing things to improve their emotional health, such as exercising or seeing friends. ‘

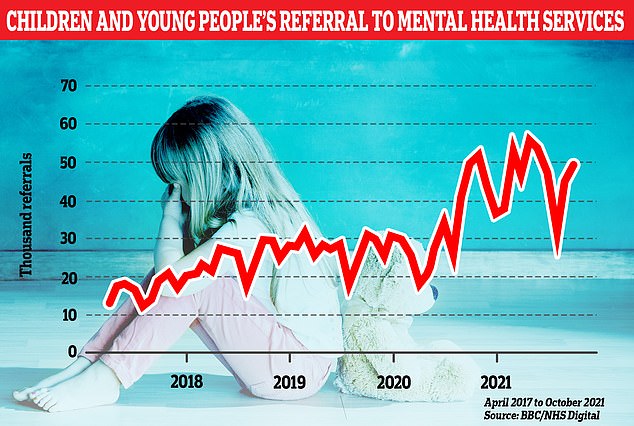

The latest statistics show that the number of people seeking help for mental health conditions has risen by two-fifths since before the pandemic to almost 4 million.

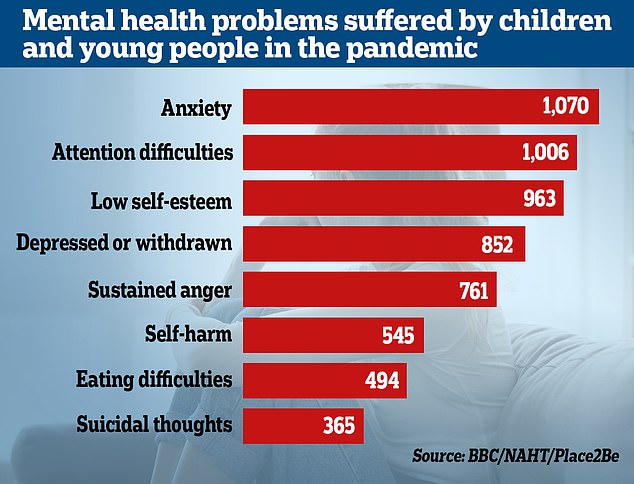

More than 200,000 children in England – or 4,000 every week – waited for treatment last year

Striking new figures show that the number of children referred for specialist anxiety treatment has doubled in just four years

Meanwhile, the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that almost a quarter of children in England now have a ‘probable mental disorder’ – up from one in five the previous year.

Professor Gerada said one of the leading causes of misdiagnosis is the widespread ‘inappropriate use’ of terms used to describe mental illness.

She said, “MeInstead of saying, “I’m sad today,” children will use the words, “I’m depressed or anxious today.”

‘People wrongly consider loneliness, homesickness, exam stress and even stress at work as a mental illness.

‘When you go to university or college, it is normal to feel lonely, to feel like you don’t know where you are, to feel homesick. That’s normal. That’s not a mental illness.

“We have to stop expecting ourselves to be miserable.”

Although many find it difficult to work when they are feeling down, the routine of working life can be an effective mood enhancer, according to Professor Gerada.

‘There is “The temptation has been to take time off work when life gets challenging,” she said. “But work is the very thing that will protect you.”

Speaking on the Jimmy’s Jobs of the Future podcast yesterday, Sir Tony said that Britain ‘very, very focused on mental health and on people’s self-diagnosis’.

The former Prime Minister added: “We are spending a lot more on mental health now than we were just a few years ago. And it’s hard to see what the objective reasons for that are.

‘Life has its ups and downs and everyone experiences them.

‘And you have to be careful about encouraging people to think they have a condition other than simply meeting life’s challenges.’

Professor Dame Clare responded directly to his comments, saying: ‘We are spending more and more on mental health care and see that mental health is getting worse and worse.

‘Mental health resources should be spent on hospital beds, patients with severe psychosis, severe depression, bipolar disorder and people with drug and alcohol problems.

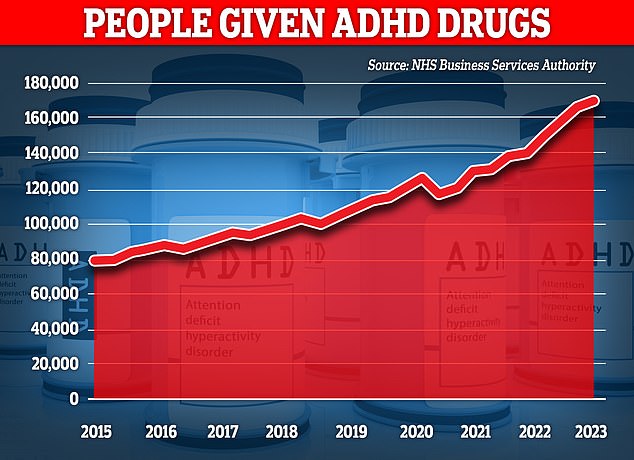

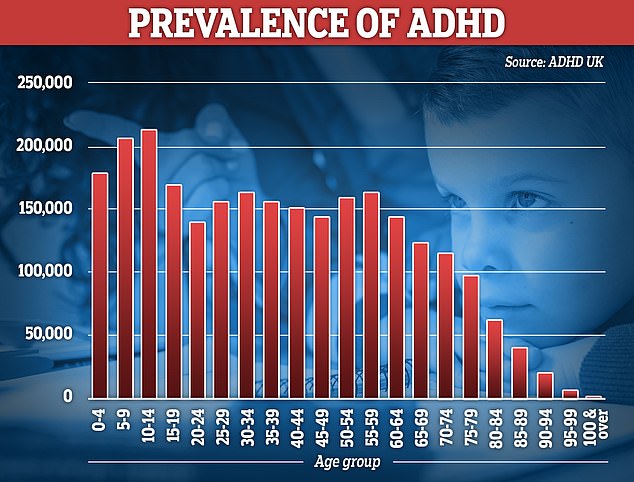

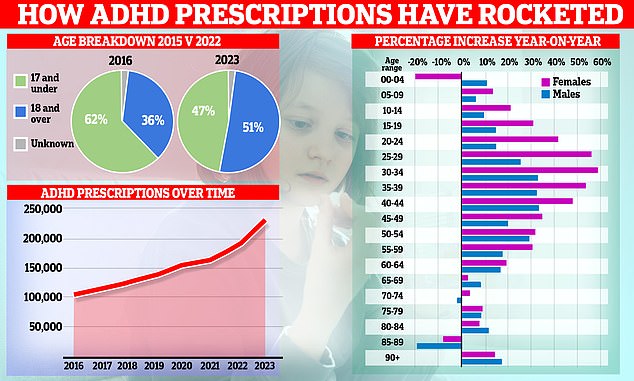

‘What we seem to be spending more and more time on is diagnosing 26-year-olds with ADHD and giving them life-long medications that can cause addiction, psychosis, dependence and physical health problems.

“We’re spending it in the wrong place.”

Last year the NHS launched a taskforce to investigate a worrying rise in the number of children and adults being diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder).

Yesterday, Professor Brendan Kelly, an expert in psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin, also warned that it was important that Britons avoid ‘over-medicalisation of cases’.

“The problems we face every day, the problems we face at work, the problems with other people – they are not necessarily mental health problems or mental illness,” he said.

“I think we need to think carefully so that we don’t deprive people of the opportunity to find solutions to problems in their lives by suddenly declaring that they are mentally ill.”

He told it The hard shoulder podcast: ‘Some of the problems in life, the ups and downs of life, the stress, some of the effects on relationships are not mental health problems – they are life problems.

“There is no point in labeling all these problems as mental health problems if it does not empower the person to find solutions.”

In October, NHS England said it was treating 55 per cent more under-18s than before the pandemic.

A spokesperson added at the time: ‘We know that much more needs to be done to reduce unacceptably long patient waiting times and ensure that every young person who needs it has access to specialist mental health care.

‘We have added an additional 40,000 mental health staff and plans are in place to ensure that more than one in two pupils and students in schools and colleges have access to an NHS mental health team in the UK by spring 2025 class, far ahead of the original goal.’

Dozens of studies have recently shown how the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns have stunted children’s development and potentially exacerbated mental health problems.

Young people from all economic backgrounds have suffered setbacks in their emotional and social development, researchers have found.

Unprecedented stay-at-home measures and school closures were among the key policies introduced at the start of the pandemic and have massively disrupted children’s lives.

In August, worrying new figures revealed that the number of children referred for specialist anxiety treatment has doubled in just four years.

More than 200,000 children in England – or 4,000 each week – were waiting for treatment last year.

This is more than 100,000 more than in 2019/2020, when there were almost 99,000 in the queue.