Mobile games no longer have to remind me how annoying my phone is

It’s been decades since games started implementing in-game communication devices that resemble our own real phones – and it’s often a successful mechanism for separating and consolidating menus, as well as tracking progress. But recently I’ve noticed a strange trend: mobile games that take place entirely inside a simulated mobile device. In other words, phone games where playing them feels like you’re on your phone. And honestly, I’m over it.

To take Guilds, the very cute turn-based RPG. The game starts with you, a character named Coda, discovering your magical phone (also called a Tome). The phone comes with a purple fairy will-o-wisp that looks a bit like your avatar to move around the world. When your Tome takes you to new places in Worldaria, you use your will-o’-the-wisp to control Guildlings (also called wizards) through combat and exploration.

Image: Sirvo Studios via Polygon

The game eventually transitions into these more complex interactions – you can walk around, explore with different items, recruit new Guildlings, and eventually fight other wisps and wizards – but for the first 15 minutes you’re basically just using a text-like chat on your magic phone to make basic decisions. It’s frustrating. And it doesn’t do justice to the game’s otherwise decent gameplay.

This chat system continues throughout the game, and its clunkiness probably won’t bother most players. But I’m running out of patience for my actual phone because at this point this thing is more of a tool and less of a gadget. When I play a game on it, I want to forget how annoying it is to use my phone. Instead, I’m often – especially at the start of a game – confronted with a UI that vaguely imitates the UI of my real phone, but with fewer decisions and less control.

There are plenty of titles that successfully mimic the design of an in-game phone. Almost every mystery game I’ve played features a phone, and it’s not the most exciting part of the game, but it’s often unremarkable: you usually get notifications triggered by location or plot, and otherwise you don’t have to use the fake phone to use . In Guildsthe game is the phone, and for that reason I really have to try to get into it. Plus, this isn’t the only instance of a clunky phone-within-a-phone game I’ve found.

In-game texts in particular feel a little tired, as this format is ostensibly a much easier way to design game conversations than animating different characters talking to each other. An Elmwood trail is an example of this. The game is well written and quite interesting, but mainly takes place in fake iPhones that only give you two options for each text you send. That’s predictable for a game, but for a phone it’s extremely limiting.

Image: Techyonic via Polygon

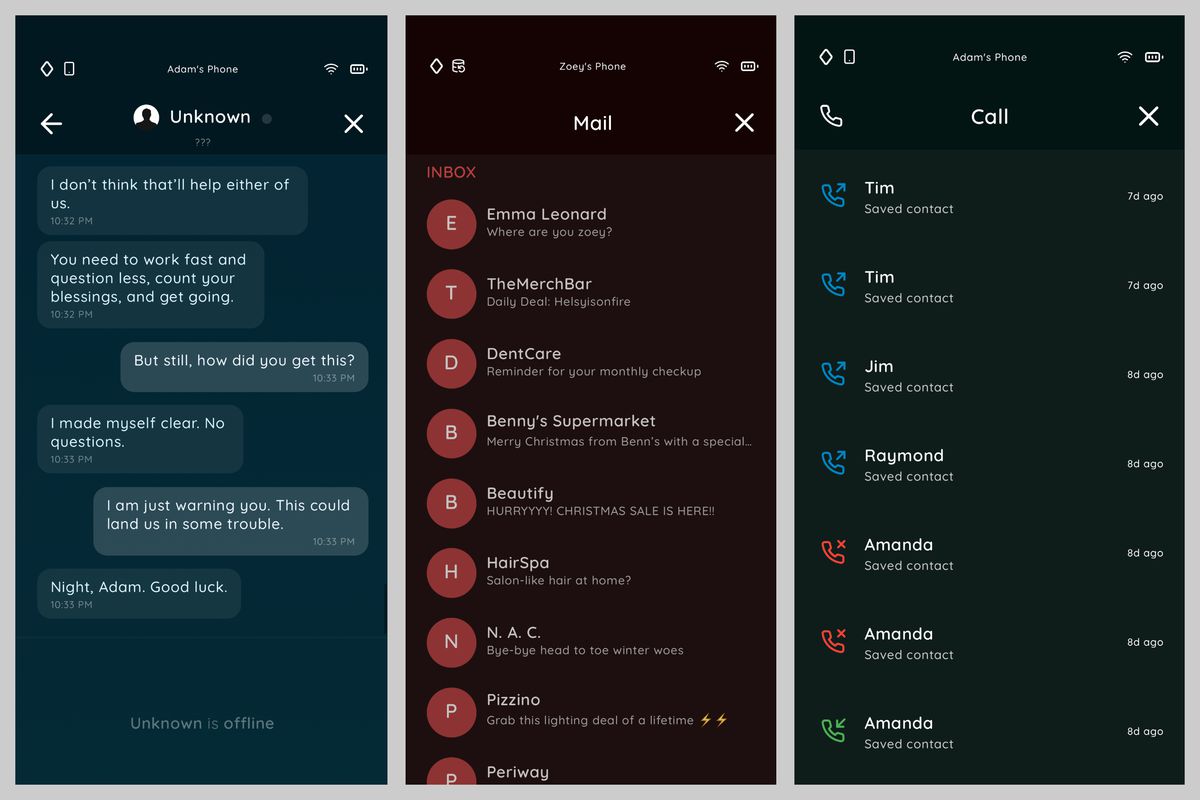

In the opening scenes of Elm wood, you are a detective who chooses answers to send to an unknown number that tries to blackmail you into solving a case. The conversation goes well, but for me it turns out to be a miss because I don’t like waiting for someone to respond to my text message. I also wish I could choose between more than two options. We know that technology exists to input our own responses and let the game digest and decide what happens next based on the keywords we send (looking at you, Doodlenauts). I realize that creating, writing and designing these types of games would be much more labor intensive. But something in between would be wonderful.

If Elm wood progresses, you’ll collect other evidence to investigate, and one of the first pieces is another character’s phone. This device has some impressive details worth celebrating: emails with clues, photos of the character’s cat, a Pixabowl app (aka Instagram).

But this setup falls short for me because it all looks so similar to my real phone that it’s almost stressful. Maybe a younger audience will think so more more attractive than a game without phones. Ultimately, I found myself wishing that developers wouldn’t rely so much on a watered-down version of a real asset that can do whatever it takes to tell their stories.

In Elm wood, you’ll eventually be able to interact with items on your desk in addition to your device-based evidence. I don’t want to jump right into this game, because it’s not bad holistically, but I do think there’s something uninspired about the use of incoming text messages and calls to introduce the story. Furthermore, I think there are much more interesting commentary out there about phones and metagaming.

Image: Nerial/Devolver Digital via Polygon

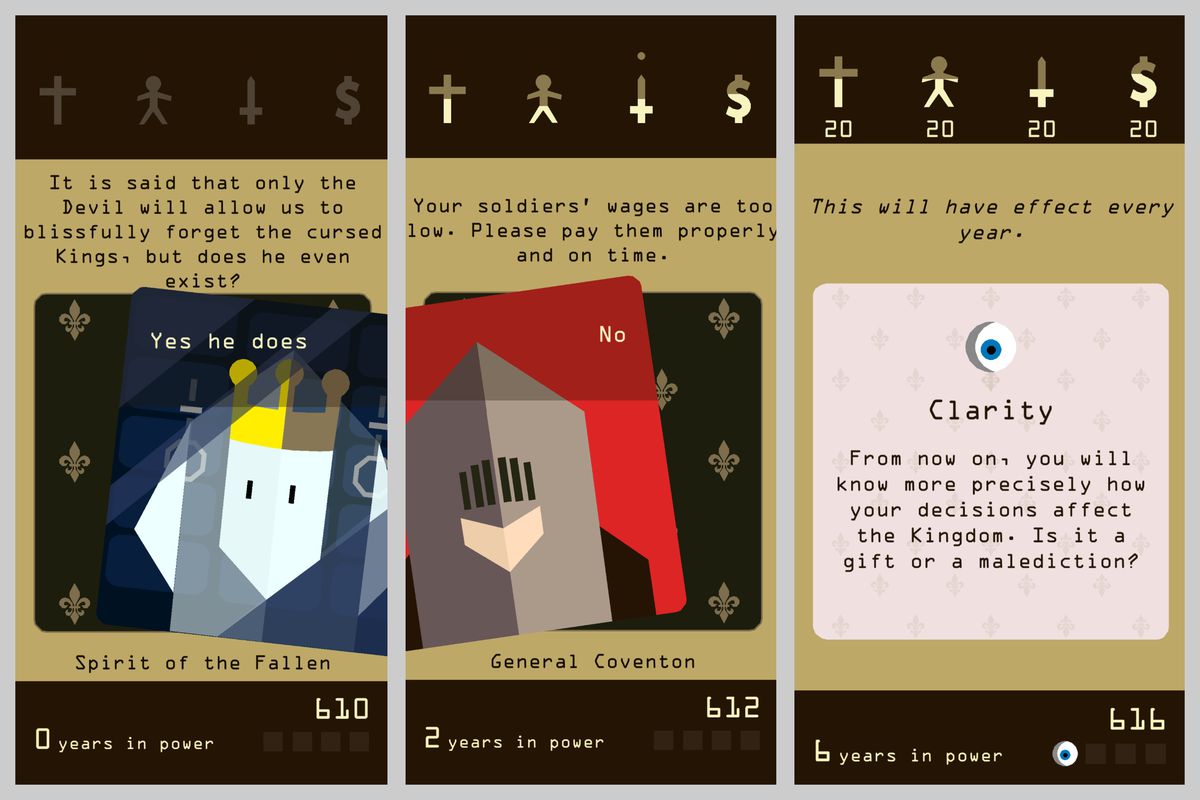

Reigns is an example of a game that uses elements of a smartphone-like user interface, but these elements are so fragmented that the experience is still very enjoyable. Using the ‘swipe left for no, swipe right for yes’ format of many dating apps, the game guides you through binary decisions that extend or shorten your reign as king. You can read it a bit as a commentary on the way we use dating apps (er, the way you use dating apps – i’m married) – don’t think, just swipe. The game even asks players to slow down and read to fully understand the implications of their decisions, which sounds like advice that many of my friends who use dating apps could internalize.

Image: Mihoyo via Polygoon

There is also Honkai: Starrail, the steamy RPG with turn-based combat – and a super-powerful in-game phone. The (very good, very fun) game takes place outside the device, which is only used for character communication and tracking missions. Honkai achieves something I haven’t seen anywhere else: the phone UI in this game is better than my real phone. It’s faster with a sleeker design and intuitive menus, along with cheeky texts that come as pleasant surprises rather than intrusive notifications.

It would be foolish to think that phones are going everywhere in games, and I actually don’t want them to do that. But I’m really more excited about mobile games that create a version of my phone that is too more more exciting than the one I use all day every day. Especially since modern phones are lightning fast and virtually ubiquitous, I like to play games that synthesize or critique our real-world use of our smartphones rather than replicate it.