Why the Menendez brothers must never walk free: MAUREEN CALLAHAN challenges Kim Kardashian and the meddling TikTok vigilantes to read all the sickening details of this case before making a terrible mistake

Think about the evidence.

As TikTok, Netflix, Ryan Murphy, Kim Kardashian and public sentiment work to free the Menendez Brothers – convicted in 1996 of the brutal murder of their parents – it is also crucial to remember why they were sentenced to life without parole release have been sentenced.

The crime itself is not, and never has been, in question.

On the night of August 20, 1989, while their parents José and Kitty were watching TV in their Beverly Hills mansion, Lyle and Erik Menendez each took a 12-gauge shotgun and fired several rounds at their parents.

Lyle was 21 years old; Erik was 18.

The mitigating factor, at their first trial and now revisited, was the alleged and credibly alleged years of sickening sexual abuse that José inflicted on both of his sons.

On August 20, 1989, while their parents José and Kitty were watching TV in their Beverly Hills mansion, Lyle and Erik Menendez each took a 12-gauge shotgun and shot their parents.

The mitigating factor, at their first trial and now revisited, was the alleged and credibly alleged years of sickening sexual abuse that José inflicted on both of his sons.

But does that justify premeditated murder? Does this mean that we, or the legal system, must now believe every claim made by these men – and not “boys,” as they were successfully rephrased during not one, but two trials – who are proven liars?

The facts of this crime, which Lyle and Erik never disputed, are as follows:

Two days before they slaughtered José and Kitty, the brothers traveled to San Diego, where they used a fake ID to purchase the murder weapons.

On the night in question, they entered the family den and shot Kitty and José sixteen times.

As recently as 2017, Erik and Lyle claimed that José had provoked a major fight, leaving the brothers in fear for their lives.

Not so. The evidence shows clear premeditation and the deliberate actions of the brothers, immediately after the murders, to create an alibi and remove all incriminating evidence.

Consider the lone voice of reason in the new, otherwise immensely likable Netflix documentary “The Menendez Brothers” — a companion piece to Ryan Murphy’s latest blockbuster “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story.”

Pamela Bozanich, a prosecutor in the case, says the back of José’s skull was blown off. As police worked the crime scene, “his brain fell to the ground,” Bozanich said.

Kitty had tried to run away. Neither Lyle nor Erik survived a shot to the torso.

Instead, Lyle went out, reloaded and returned, placed the muzzle against Kitty’s cheek and pulled the trigger, leaving her unrecognizable.

As Lyle herself testified, “I reached out and shot her at close range.”

The brothers also shot José and Kitty in the knees, making it look like a mafia attack.

Then they drove to a local movie theater and bought tickets. This would be their alibi – they were at the cinema – and would return home to hide all the spent shell casings and get rid of the murder weapons, which were never recovered.

It wasn’t until the scene was cleared of evidence that Lyle called 911.

“Someone killed my parents!” he wailed.

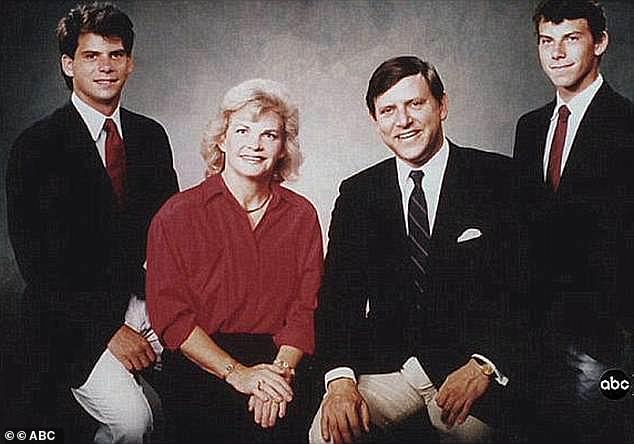

But does that justify premeditated murder? Does this mean that we, or the legal system, must now believe every claim made by these men, who are proven liars? (Photo: Lyle (left) and Erik with their parents José and Kitty.)

When police arrived, they found the brothers hysterical — “overreacting,” Bozanich says — and treated them as victims, not suspects, even though parricides are usually committed by young, white men with no history of violence.

Investigators didn’t even test Lyle and Erik’s hands for gunshot residue, which the brothers later admitted was still all over their hands.

Erik and Lyle were both interviewed for this new Netflix doc, speaking by phone from prison.

“It’s actually unbelievable that we weren’t arrested that evening,” Erik says. “We should have been.”

In the immediate aftermath, as Beverly Hills police searched for the killer (or killers), the brothers eagerly spent their $14 million inheritance. Among their purchases: a new Porsche Carrera, a Jeep Wrangler, three Rolexes, two restaurants and a $50,000-a-year tennis coach.

All of that, Lyle now claims, was a bit of retail therapy – in the literal sense of the word.

“Everything,” he says in the doctor, “was to cover up this terrible pain of not wanting to live.”

Months after the murders, during a conversation with his therapist Dr. Jerome Oziel – an admittedly controlled character who later gave up his license after violating professional ethics – confessed to Erik.

Oziel testified that Erik went into great detail: His father, he said, was a “dominating,” “impossible to please” perfectionist. Kitty, he said, was collateral damage.

“The mother was brought into the scheme because she was said to have been a witness,” Oziel said during the trial.

Oziel said the brothers also rationalized her murder as a favor — that her life without José would have been so depressing that killing her was a form of “euthanasia.”

Oziel, who had started recording his sessions with Erik, asked Lyle to come in.

Again: confess to murdering their parents? No problem. Recognize serious sexual abuse as a mitigating circumstance? Never brought up.

Incredibly, Lyle now complains to Netflix that Oziel’s betrayal was particularly painful — that he thought “a normal therapist” would deal with this — their confessed parricide — “in a confidential way.”

Now: Were Lyle and Erik abused by their father? Most likely.

Since their conviction in 1996, new evidence has emerged: a letter Erik wrote to his cousin months before the murders, which strongly suggested that he was sexually abused by José: ‘I tried to avoid dad… I know never when it’s going to happen’ that’s going to happen… Every night I stay awake thinking he might come in’ – adds credibility to their claims.

The same goes for the accusations made by Roy Rosselló, former member of the Puerto Rican boy band Menudo, who says José drugged and raped him as a teenager.

However, it seems notable that the brothers’ attorney, Leslie Abramson, whose so-called “abuse-excuse” defense resulted in a hung jury in the first trial, declined to be interviewed by Netflix.

In a statement, she said: “I would like to leave the past in the past.”

That, in my opinion, is quite devastating. If the world finally comes to a defense that was considered laughable at the time – well, why not take your victory lap?

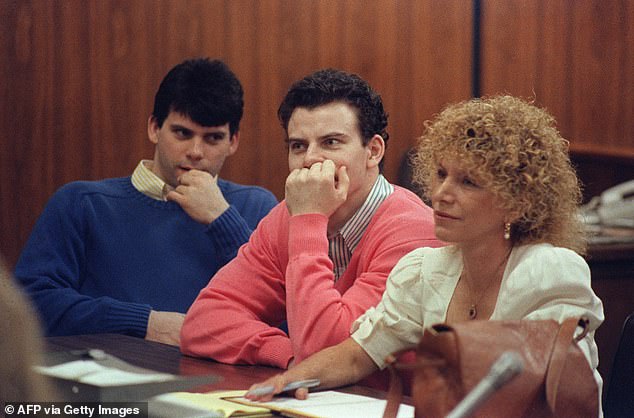

The brothers’ attorney, Leslie Abramson (right), whose so-called “abuse excuse” defense resulted in a hung jury in the first trial, declined to be interviewed by Netflix.

Do we allow Gen Z to recite longstanding crimes on TikTok? Will Kim Kardashian – who plays a lawyer in her wigs and Skims thongs – make a ruling?

Especially since we are on the verge of a historic outcome: the Menendez brothers could very well be released.

What does that mean for the future?

Do we allow Gen Z to recite long-standing crimes on TikTok? Will Kim Kardashian – who plays a lawyer in her wigs and Skims thongs – make a ruling? Do Netflix documentaries dictate the scale of justice?

And does child abuse now mean that all forms of vigilante justice are forgiven? Is that premeditated murder now justified?

Note Prosecutor Bozanich, who readily admits that Jose was a “monster” and that his death “was a real plus for humanity.”

“The only reason we’re doing this special,” she says, “is because of the TikTok movement… If that’s the way we’re going to handle things now, why don’t we just do a poll? Everyone can vote on TikTok!… Your beliefs are not facts. They’re just beliefs.’

Keep that in mind as celebrities, Menendez family members, and Gen-Z protesters gather at a press conference in LA today and demand “justice” for these cold-blooded killers.

If they win, Lyle and Erik Menendez will undoubtedly get a jubilant cover of People magazine, a book deal worth millions of dollars, a reality show and a re-entry into polite society.

Is that real justice?