Megalopolis is a fantasy disaster story, but this book explains why it exists

I heard the same question before and after seeing Megalopolis: What the hell is this Megalopoliswhat is it about?

In the press for the film, director Francis Ford Coppola, of Apocalypse Now And The godfather fame, has long talked about Megalopolis a wake-up call for audiences to take up arms for the future of cinema and society as a whole — a bold act of optimism that envisions a path to utopia. But the film, which opens in theaters this week, is really about history, and specifically Coppola’s personal past.

The 150-minute fever dream of philosophy, politics and Shia LaBeouf’s mullet isn’t subtle. Characters with names like Cesar Cataline and Wow Platinum deliver dozens of exhaustive monologues about the power of art, the calcification of bureaucracy and the need for grand, all-encompassing debates about the future. At one point, the antagonist delivers a speech from a tree stump sculpted into a swastika.

There is nothing “sub” about the subtext here. It’s as crass as a chain letter you got from your grandfather. And yet all of these tirades are far more interesting and digestible than the considerable amount of time Coppola’s heroes spend defending Coppola’s actions.

Adam Driver’s Cesar, the urban designer of Megalopolis, mourns his wife, whose life was figuratively and literally invested in his work — the film suggests that her DNA powers the film’s fictional building material, Megala. Coppola is notorious mixed his marriage and art in ways that led to bitter fights and affairs. Cesar takes extreme measures to build his dream city of art, destroying buildings and opposing public services. In the 1970s, Coppola hoped to destroy the studio model through independent financing, and for his early films he fled Hollywood to avoid union labor.

The list of similarities goes on and on, to the point that Megalopolis feels less like a film than a plea for Coppola’s legacy – which makes sense, given the filmmaker’s use of his wine empire, his fortune and his debts narrate are story. What better reason to spend your fortune before you die than to ensure that you are remembered fondly when you are gone?

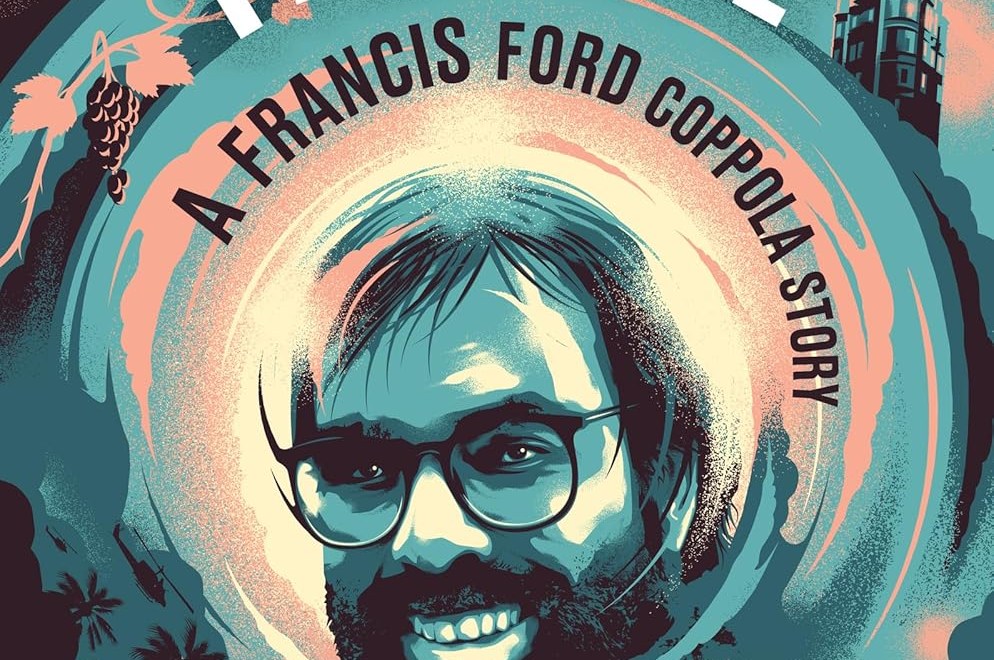

Megalopolis is a strange experience that anyone who wants to hear Driver recite can “enjoy” Hamlet and Aubrey Plaza make a celebration of some of the year’s most insane lines. For most viewers, however, much of the richer meaning will be lost without knowledge of Coppola’s story. Fortunately, that’s easier than ever thanks to a fantastic new biography from Sam Wasson, The Path to Paradise: A Story by Francis Ford CoppolaCoppola and his colleagues collaborated on the book, and they offer a shockingly candid and comprehensive look into the personal life and career (the two are often used interchangeably) of one of the greatest artists in film history.

The book tells the story of a man who was willing to bet everything on himself over and over again. For a while, his bet worked! Over and over again! And then his luck ran out. Have you seen jack?

Wasson’s book is remarkable in its lack of judgment. The author gives Coppola ample space to reflect on his life, and unlike Megalopolisoffers that history and analysis in a clear, relatively chronological and humane way. Coppola comes across as a genius, a cod, a visionary and a man struggling with his sanity in an era that lacked the tools and language of today. Where Megalopolis tells the story of a Great Man, The path to paradise tells the story of a man who was not so different from others, but who — at the expense of himself and those around him — achieved great things.

As a standalone film, Megalopolis is a mess — the kind of movie that leaves audiences scratching their heads as they walk to their cars and forgetting the story on the drive home. But with a sampling of Coppola’s history, the film becomes something, if not good, then at least special. A scene in which Cesar’s enemies attempt to smear the artist with an affair, for example, takes on new meaning when you consider that Coppola once sent a heated memo to his staff calling for the firing of key team members when rumors spread through Zoetrope about his infidelity during the making of Apocalypse Now.

With the book as a key, we can open Megalopolis and discover what lies within: an artist’s $120 million autobiographical reckoning, reflecting on his creations, his enemies, his dreams, and the question that haunts us all. Have I done enough to leave the world a better place than I found it?

Of MegalopolisCoppola defends himself in court as if the audience is not on Earth but a divine bouncer in the afterlife.