Meet the plant detective who helped solve the Pret sandwich tragedy and is now exploring new ways to treat cancer

Professor Monique Simmonds had half expected the call in her laboratory in Kew Gardens in south-west London.

Lawyers investigating the death of 15-year-old Natasha Ednan-Laperouse had already asked her for help as one of the country’s top plant detectives.

Natasha, from London, had died following a severe allergic reaction she suffered on board a flight to Nice in July 2016 after eating a baguette she bought at Pret A Manger.

At the time it was unclear what had happened, and investigators asked Professor Simmonds to examine the contents of Natasha’s stomach to determine what had caused her death.

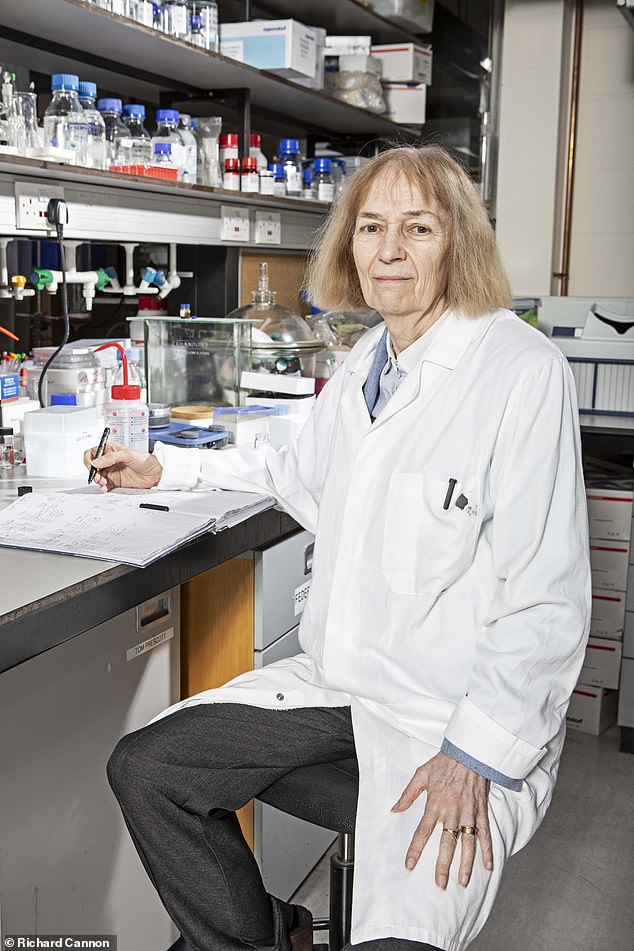

Professor Monique Simmonds OBE Deputy Director of Science at Roayal Botanical Gardens, Kew

The Palm House of Kew Gardens in Greater London

The contents were compared with 8.5 million samples in the plant compound database at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. A match was found for sesame, to which Natasha was highly allergic, but which was not on the label of the baguette.

A few months later, Natasha’s father, Nadim, visited the laboratory at Kew with a seed from the brace Natasha was wearing when she died. He wanted Professor Simmonds to confirm whether it was sesame.

“We had already identified sesamin (a compound in sesame) from the stomach contents,” said Professor Simmonds, deputy director of science at Kew. ‘When we examined foods from the bracket, we found a lot more sesame. What emerged at the 2018 inquest into Natasha’s death was that the baguette dough was made with sesame.’

This meticulous plant detective work is not unusual for Professor Simmonds, who has worked at Kew since 1985.

At the request of police or coroners, she helps solve crimes by analyzing the surrounding fauna and flora for clues, or by analyzing stomach contents for a poison or allergen that may be related to plants and fungi.

Professor Simmonds and her team are also using Kew Gardens resources to find ‘natural’ solutions to some of the biggest health problems, including malaria and antibiotic resistance.

The scale of resources at Kew is staggering. The gardens employ 470 scientists, have a fully equipped chemistry laboratory and more than 2.4 billion seeds, which are kept in pots at -15 degrees Celsius in vaults at Wakehurst, near Gatwick.

Professor Simmonds and her team are also using Kew Gardens resources to find ‘natural’ solutions to some of the biggest health problems

Professor Simmonds has worked at Kew since 1985, doing plant detective work

Known as the Millennium Seed Bank, it has been 24 years in the making and includes 40,000 wild plant species from 190 countries and territories – which is more than 10 percent of the world’s flora – making it the most diverse seed bank in the world. world.

Kew also has a library containing 8.5 million samples of dried plants collected over the past 200 years, a Fungarium containing more than a million dried species of fungi, as well as the living plants that visitors to the gardens see.

‘These collections are for conservation purposes, but also so we can look at the chemistry of plants to find medicinal properties,’ says Professor Simmonds. There is enormous untapped potential in using plants as medicine. ‘Although more than 25,000 of the world’s plants have documented medicinal uses in early texts from Persia and China since 2000 BC, only about 200 have been recorded in Western medicine,’ says Professor Simmonds.

Natasha Ednan-Laperouse who died after eating a Pret A Manger sandwich

Natasha pictured on a British Airways flight just before she died

She believes greater use of plants in medicine could be “game-changing.” The use of plants is already established for some medical conditions.

‘For example, vincristine from the periwinkle plant and taxanes from the bark of the Pacific yew tree have anti-cancer properties and have been converted into chemotherapy drugs used routinely by the NHS,’ says Professor Simmonds.

And while plants can be the cause of allergies, they may provide a solution in the future, she says.

‘For example, lipid transfer proteins occur in all kinds of fruits, vegetables, nuts and grains to protect the plant, but can also cause serious allergic reactions. There are other proteins in plants called Gibberellin-regulated proteins (GRPs) that are linked to several fruit allergies.”

Fruits that contain GRPs include peaches, sweet cherries, oranges, pomegranate and strawberries.

To prevent these allergies, plant breeders could theoretically reduce levels of these proteins, says Professor Simmonds.

One of her current research projects investigates plants as a way to treat inflammation, which is involved in everything from heart disease and dementia to cancer, asthma and aging.

Professor Simmonds and Professor Clare Bryant, a consultant in clinical pharmacology at the University of Cambridge, are investigating plants that can both cause and moderate inflammation.

Current treatments, including anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen, slow the production of prostaglandins – hormone-like chemicals that play a role in the body’s inflammatory response – but do not address the underlying causes and can also lead to side effects such as stomach ulcers.

‘We believe that rather than a single drug to treat inflammation, a multifactorial approach would be better, using drugs and botanicals together,’ says Professor Simmonds.

She and Professor Bryant use artificial intelligence (AI) to identify plants and fungi that may influence inflammatory pathways as we age.

‘We’ll start with traditional Chinese medicines that are already thought to reduce inflammation – to prove whether they work,’ explains Professor Simmonds.

‘We want to understand which receptors they act on and whether you need more than one plant to have a protective effect.

Current research projects include investigating plants as a way to treat inflammation. The Palm House in Kew Gardens

Last year, Kew scientists identified thousands of plant species that could be potential new treatments for malaria. Pictured: Kew Gardens

‘With a better understanding of inflammation and help from AI, we hope to identify new plants that contain ingredients that can protect against inflammation.’

She adds: ‘Herbs that show potential include rosemary, turmeric, sweet balm and licorice.

‘This could be important for a range of diseases, from cancer to dementia, and we hope that in five to ten years our research will lead to new plant-based treatments for inflammation.’

Breakthroughs are happening all the time. Last year, Kew scientists identified thousands of plant species that could be potential new treatments for malaria – one of the world’s biggest killers.

Resistance to the two most important drugs – quinine and artemisinin (both derived from plants) – is increasing. In a study published last May, scientists assessed 21,000 species from three plant families, some of which are native to Britain – and estimated that more than a third could have antimalarial properties.

“Our results highlight the enormous undiscovered potential of plants to produce new medicines,” says research colleague Adam Richard-Bollans.

‘There are an estimated 343,000 known plant species, many of which have not yet been subjected to any scientific evaluation for their medicinal uses.’

But a new treatment isn’t just about identifying a plant for its medicinal properties.

Scientists also need to figure out how to prepare and take it, and what the required dose is.

Another Kew study, Remembered Remedies, examined pre-1948 ‘old wives’ tales’ collected from interviews with people in rural areas from Scotland to Cornwall in the 1980s.

This included the herbal ajuga for the treatment of cough. ‘When we first made and tested an extract from these plants we got nothing,’ says Professor Simmonds.

‘So we did more digging, including talking to herbalists who use these plants, and discovered that picking them in the spring instead of the fall, for example by using specific parts of the plant – and using them fresh instead of dried – made a difference. how effective it was.’

Meanwhile, for Nadim Ednan-Laperouse, Professor Simmonds’ work provided the answers, however painful, that he and his wife Tanya were looking for.

“By analyzing the remains of Natasha’s brace, we were able to prove beyond doubt that she had eaten sesame, which caused fatal anaphylaxis,” he says.

‘She thought the baguette was safe for her to eat. It wasn’t.

“Having that information has led to tremendous changes for the two to three million people in this country with food allergies.”

In 2021, the introduction of Natasha’s Law meant that all food retailers must now provide full labeling of ingredients and allergens on products pre-packed for direct sale. Nadim says: ‘Every day it protects people with food allergies from potentially fatal allergic reactions.’