Meet the Man Who Created Our Vision of Hell: Scientists Reconstruct Dante’s Face for the First Time in More Than 700 Years

The man who created our vision of hell has been seen for the first time in more than 700 years after scientists rebuilt his face using his skull.

Dante Alighieri became an icon of Western literature with his writing, and his magnum opus was the Divine Comedy, which described a journey to heaven, hell and purgatory.

His description of hell is now the standard – an inferno of nine circles where the worst offenders are confined to the deepest recesses and sinners receive ironic punishment for their misdeeds.

But despite his lasting legacy, the artist’s true face is shrouded in mystery, with the most popular paintings of his likeness created long after his death.

Now a new study has revealed what the man himself looked like, using Dante’s skull to digitally recreate the literary icon’s appearance.

The man who created our vision of hell can be seen for the first time in more than 700 years after scientists rebuilt his face using his skull

His description of hell is now the standard – an inferno of nine circles where the worst offenders are confined to the deepest recesses, and sinners receive ironic punishment for their misdeeds

Brazilian graphics expert Cicero Moraes, the study’s lead author, described why traditional depictions of the poet fell short.

He said: ‘Most are based on the information in the biography of Dante, compiled by the writer Boccaccio.

‘Namely, that he was an individual of medium height, slightly stooped, with a long face, an arched nose and eyes that were large rather than small.

‘Boccaccio, however, did not know Dante personally and collected reports from people close to the poet and living with him.

“All approaches seem to follow Boccaccio’s descriptions, but we try to do strictly what the bones indicate.”

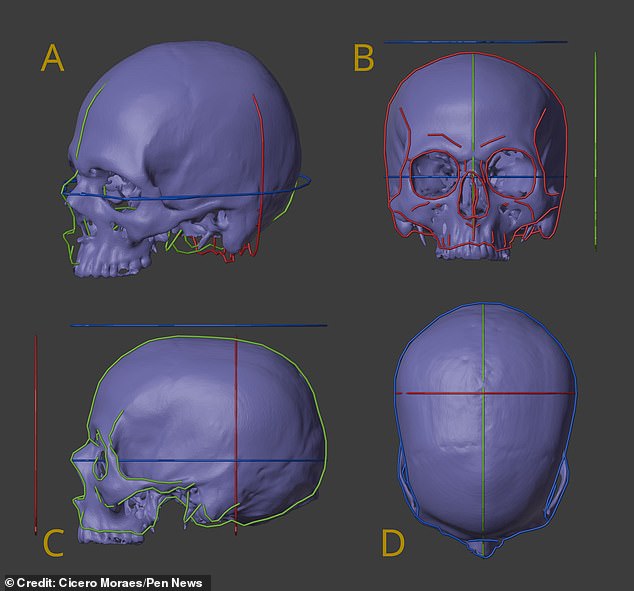

The authors began by digitally reconstructing the Italian poet’s skull, based on a 1921 analysis of his bones, supplemented with data from a 2007 article about his face.

Mr Moraes said: ‘We then moved on to the facial approach.

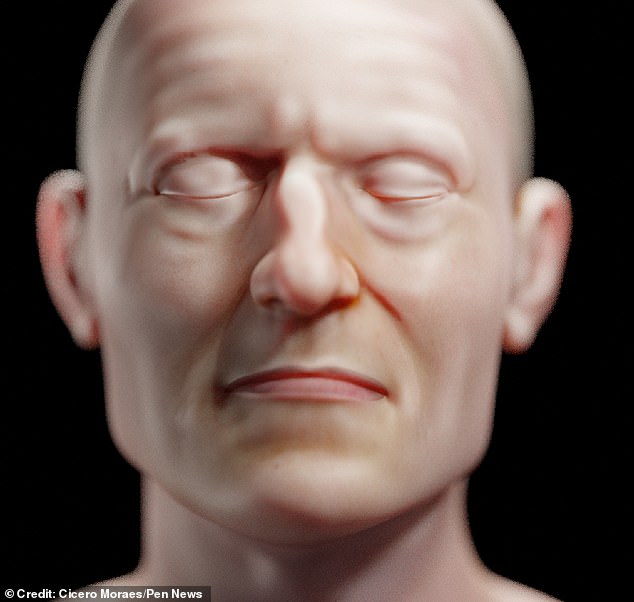

‘This consists of making a series of projections based on statistical data from tomography and ultrasound analyses, and crossing them with the anatomical deformation.’

The authors began by digitally reconstructing the Italian poet’s skull, using a 1921 analysis of his bones, augmented with data from a 2007 paper on his face.

The project found that Dante – often hailed as the father of the Italian language – had a larger-than-average skull.

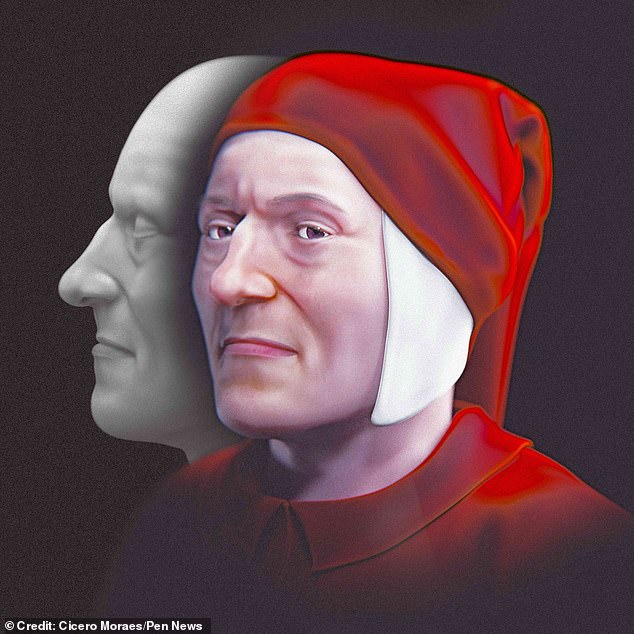

Anatomical distortion occurs when a living donor’s digitized face is deformed until it fits the skull in question, creating “a face compatible with that of the poet in life,” Mr. Moraes said.

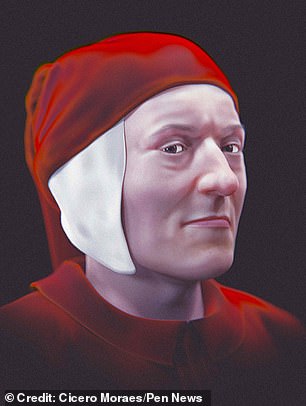

He continues: ‘Two sets of images were generated, one with an objective approach, in grayscale, without hair and with closed eyes.

‘And another in color and with subjective elements, such as the color of the eyes, skin and clothing, according to the best-known images.’

Dante was unluckily banished from his native Florence in 1302 and died in Ravenna in 1321.

Moraes said the face they created betrayed a tormented man.

“It shows a brilliant man, but embittered by exile,” he said.

The project also found that Dante – often hailed as the father of the Italian language – had a larger-than-average skull.

Mr Moraes said: ‘There is a big debate about a bigger brain having greater intelligence.

‘Even if we ignore this approach, the fact is that Dante’s work was that of an individual of genius.

This photo shows an 1850 image of Dante (seen wearing a red hood) visiting Hell, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

“Approaching Dante’s face is, in a way, a tribute to my own family’s history,” the artist said

‘It was full of universality that influenced not only world literature, but also the organization of a language and – perhaps a little exaggeratedly – the creation of an entire nation.’

He continued, “I felt very honored to work on this; my great-grandparents were Italian and my mother spoke a language from the region until she was 17.

“Approaching Dante’s face is, in a way, a tribute to my own family’s history.”

Cicero and his co-author, Thiago Beaini of the Federal University of Uberlândia, published their research in the 3D computer graphics journal OrtogOnLineMag.