Massacre of the innocents: More than 330 people – including 186 children – died at Beslan. Reporting on it gave journalist Tom Parfitt nightmares which he finally overcame by trekking through the region’s mountains

MEMOIR

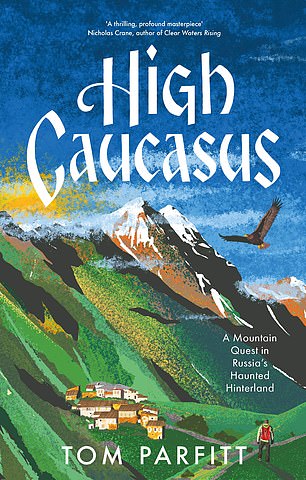

High Caucasus

by Tom Parfitt (Headline £25, 332pp)

The children arrived at school on September 1, 2004, the first day of the school year, ‘with new school bags and bunches of flowers for their teachers’. . .’

One of the first-graders, seven-year-old Dzera Kudzayeva, was chosen for the “first bell” ritual, in which a new girl is hoisted onto the shoulders of one of the oldest boys and rings a handbell. The city was called Beslan.

Shortly after the children gathered, the militants arrived. They jumped off a flatbed truck, fired automatic rifles into the air and shouted Allahu Akbar!

They shot two guards and then took hundreds of children and their teachers hostage in the school.

Terror: Schoolchildren are rescued from siege in 2004 after being taken hostage along with their teachers by Chechen militants

Days passed; The situation became chaotic, with local men arming themselves with guns and Russia’s ruthless special forces, Spetsnaz, arriving.

The militants were Chechens, who sought revenge in the pro-Russian Christian republic of North Ossetia for the countless atrocities Russia had inflicted on their own Muslim homeland of Chechnya, repaying the brutality with even worse brutality.

They released a few nursing mothers and their babies, but the rest of the captured children were stripped to their underwear, herded into a scorching gymnasium and denied drinking water. They were forced to drink their own urine.

Ultimately, chaos broke out, bombs exploded, a fire broke out and the building was stormed – resulting in the deaths of 333 people, including 186 children.

Parfitt, a Moscow correspondent for British newspapers, saw it all.

‘In the arms of a man, a girl of about nine years old had blood streaming from the corners of her mouth. . . the bodies of four children lay covered with sheets. . . a man in camouflage with his fists in bloody rags. . .’

Many journalists witness terrible things to bring us the news, but Beslan was a particularly horrific mass murder of innocents.

Although Parfitt bravely insists he hasn’t suffered from PTSD since, he certainly had a hard time with it.

Tom Parfitt, a Moscow correspondent for British newspapers, saw the Beslan massacre firsthand and experienced recurring nightmares in the aftermath. Parfitt realized he had to do something and turned to nature

Soon there were recurring nightmares, especially one in which he saw a mother who had just lost her child in the massacre, falling to the ground in slow motion, “thrashed, diving before my helpless vision.” Three seconds withdrawn from a coil of fear and slowed down in an endless purgatory.’

One evening, “I was putting on my socks when I started babbling incoherently.” He decided he had to do something.

And so he did what many traumatized survivors have done: he turned to nature, to the mountains, to forests and rivers, and to the slow, wordless magic of a very, very long walk.

He traveled from end to end across the Caucasus Mountains, through the many troubled but beautiful republics, such as Ingushetia, Dagestan and Chechnya itself: eight regions in all, all but two of which the Foreign Office advised against visiting.

Parfitt hoped to experience a calmer area, find his own peace and try to understand how something so horrific could have happened.

The result is this book, High Caucasus, one of the most moving, beautifully written and beautiful accounts of a mountain trek I have ever read – an instant classic.

You could describe it as a secular pilgrimage in search of some form of redemption, or at least partial healing and understanding.

Parfitt absolutely loves this landscape: ‘The North Caucasus had cast a spell over me that no place has ever equaled before or since.’

Parfitt met countless cheerful, if often drunk, shepherds, always eager to force vodka on this exotic foreign hiker and discuss the world together

A gripping and beautifully written account of a mountain trek, Parfitt’s High Caucasus is an instant classic

He vividly evokes a world in which life is very hard, but so are the people: a world in which Abkhaz women travel miles across the border to sell armfuls of mimosa blossoms to the Russians for a few rubles, while the men bear shoot and then ‘sell’. the fat people rub on their chest when they are sick’.

He meets countless cheerful, if often tipsy, shepherds with enormous mustaches, wearing sheepskin coats, who spend months with their flocks in the high summer pastures, defending them from wolves and sleeping in sparse huts.

They are always eager to give this exotic foreign hiker vodka and discuss the world together.

An Orthodox priest tells him that he has heard that London is very bad in terms of crime. “East 17,” he said. “Same as the group.” ‘Ah,’ says Parfitt, ‘Walthamstow.’

There are many such comedic moments, like when he fears he’s going to get into a gunfight and hears bullets flying, but a local assures him, “Probably a wedding.”

Head £25, 332pp

He soon comes across “a pristine blue Rolls-Royce Phantom with a man sitting on the passenger window firing a Kalashnikov into the air.” All very cheerful, nothing to worry about.

Parfitt concludes his great adventure with the feeling that history is something that all peoples must remember and forget, lest they become trapped in an attitude of smoldering hatred and desire for revenge.

And yes, nature heals, just like long days with simple but far from stupid people.

Finally, the Caucasus comes to mean not only the horrors of Beslan, but also ‘a curtain of clouds rising like smoke over a mountain ridge’. . . a bowl of mulberries on a sunlit windowsill’, while ‘above all, filling the horizon from west to east in a chain of wonder, rises the icy palisade of the mountains: vast, sparkling, unchanging’.

A magical book.