I found my teenage son Mac Holdsworth dead in his room after he was caught up in a sextortion scam but I was banned from saying anything to the man responsible for his tragic end – until now

Wayne Holdsworth has never been the same since the terrifying moment he discovered his son hanged in his room just hours after taking his own life.

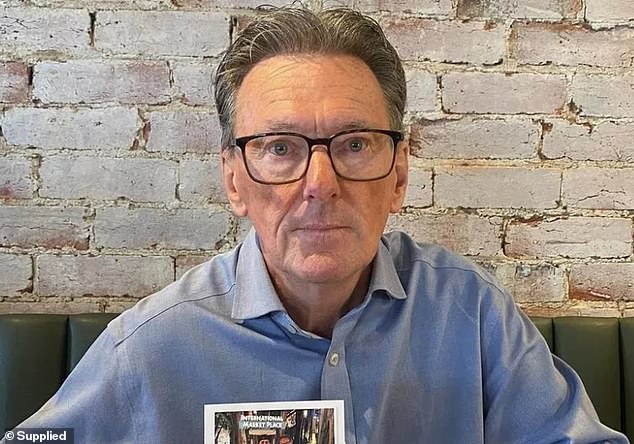

Father-of-two and CEO of the Frankston & District Basketball Association, Wayne never suspected his 17-year-old son Mac was struggling.

Even in the hours before he killed himself, the teen had been cheerful, joking with his sister and even making plans for the next morning.

Wayne now knows that Mac felt like he was about to be freed from the brutal sextortion scam that had turned the last phase of his life into a hellish trauma.

Mac had been tricked into sending an intimate photo to someone he thought was a teenage girl on Instagram.

Pictured is the latest photo of Mac Holdsworth, 17, and his loving father Wayne

Instead, the photo was delivered to a 45-year-old pervert from NSW, who then used it to blackmail Mac and threatened to send the photo to the boy’s friends and family.

The man demanded $500, which Mac quickly sent. Then came a demand for another $500.

The man told Mac that his family “hates” him and that he would want to kill himself if the photo were ever shared online.

Mac admitted the situation to his father and the police, and when they made efforts to track down the perpetrator, he hacked into Mac’s Instagram account and sent the intimate photo to his inner circle.

Mac tried to laugh off the incident with his friends, but inside he felt hurt and humiliated.

Police were able to charge the man over the sextortion scam, with Mac asked to prepare a victim impact statement to be read out in court.

The teen took his own life before he could confront his abuser.

“He never got over that in my opinion,” Holdsworth told Daily Mail Australia.

“The suicide letter he wrote indicated that.”

While searching for his iPad and computer, Wayne found a letter from Mac apologizing for being a burden to his family.

After the death of his son, Mr. Holdsworth traveled from Victoria to Liverpool Court in Sydney’s west in the hope he could read his own victim impact statement to the man who destroyed Mac’s life.

However, he was not allowed to read the statement after the man pleaded guilty.

“He was sitting there behind the glass. I went there thinking, “I’m going to keep an eye on this guy and I’m going to make the impact statement.”

“Well, I was shaking and I’m a pretty strong guy, and the lead detective put his arm on me and said, ‘It’s okay, Wayne, don’t worry.’

“But the prosecution and defense got together and they didn’t allow me to read the victim impact statement. They made a deal where if he pleaded guilty, he would get six months in prison.

‘I wasn’t angry, I was just disappointed in the system that made that possible. I have spoken to both the defense and the prosecution and given them my opinion.

‘I was really disappointed. I asked the defense attorney: has he shown any remorse? aand she said “no”.

‘When the magistrate asked whether he would plead guilty or not, he said: ‘Yes, I plead guilty, but I am the victim.’

“So that confused me a little bit.

‘He got six months and because he spent three months on remand he is now free and I have no doubt he will do exactly the same thing again.’

Wayne Holdsworth has made it his life’s mission to teach others about suicide prevention

Mac took his own life exactly 100 days after his mother Renee died following an 18-month battle with multiple sclerosis.

“I’d ask him, ‘Are you okay?’ ‘How are you?’ and he said, ‘I’m fine, Dad’ and changed the subject,” Wayne recalled.

“His upbeat attitude, especially toward the end, indicated that he got through everything, that he was doing well, and it was quite the opposite.”

Although the online extortion was the major tipping point in his son’s suicide, Holdsworth believes another incident that damaged Mac’s mental health was an internship with a local electrician.

At first Mr Holdsworth thought the electrician was a nice guy, but he noticed that when he picked Mac up from the job site, his son It was unusually quiet on the ride home.

One afternoon, Mac burst into tears as he described being called a “useless bastard” after putting tools back in the wrong place.

Wayne quickly realized he was being bullied and confronted the man.

“We had to get him out of there and Mac’s life was kind of turned upside down because he planned to be a bubbly kid,” Wayne said.

‘He used to walk around to his mate’s house in his kit with the boots and the fluro-jet vest and this was taken away from him very quickly.

‘I called [the electrician] and I said, “Is this true?” and he said, “Yes, it is, I have to do better.” So there was no denying what had happened and Mac was hurt by that.”

Mac was able to teach himself and find a job in retail before starting as an apprentice carpenter in another workplace, where he did well.

Mac is remembered as a beloved friend and son who loved sports and tradie

His death came as a shock to many, with 700 people attending his funeral at Connect Christian Church in Frankston, in Melbourne’s south-east.

Mr Holdsworth was understandably devastated by the death of his son so soon after the loss of his wife, and saw three options: commit suicide, live aimlessly or dedicate his life to suicide prevention.

Since Mac’s death on October 23, Mr Holdsworth has spoken to parents and young people almost every day about mental health and the rising suicide rate.

He has founded a non-profit organization called Smack talk where he shares his story with groups and teaches them how to recognize the signs that someone is having a hard time.

After presenting to 1,000 people in six weeks, twelve people came forward for help.

‘Apparently part of grieving is finding something that makes you feel better. And people talk about cycling, walking or doing something physical,” he said.

“Well, this is mine…I have an absolute obligation to help other families by sharing my story and presenting some proven guidelines that I hope can help.”

If you or someone you know needs support, please contact Lifeline 131 114 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636.