Long-lost Neanderthal group that lived 50,000 years ago has been discovered and has links to ‘The Hobbit’

A new DNA analysis of a Neanderthal nicknamed Thorin is causing experts to rethink what they know about early humans.

In 2015, researchers discovered the remains of the little Thorin in a cave in southern France. He is named after the character in JRR Tolkien’s famous book ‘The Hobbit’, the last of the dwarf kings.

However, new research into Thorin’s DNA suggests that he belonged to a previously unknown lineage of Neanderthals, which lived in isolation for 50,000 years, despite living in close proximity to other members of their species.

Paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak, who co-led the new study, said: ‘How can we imagine populations that lived in isolation for 50 millennia, when they are only two weeks’ walk apart? All processes have to be rethought.’

DNA analysis of Thorin’s remains revealed that he belonged to a previously unknown group of Neanderthals that remained isolated for 50,000 years

Scientists believe Thorin lived about 42,000 years ago, around the time our closest human relatives disappeared.

This discovery complicates the story of the origins of modern humans and raises new questions about when and why Neanderthals disappeared.

Slimak – from the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse, France – first discovered Thorin’s remains almost 10 years ago in the entrance to the Grotte Mandrin rock face in the Rhône Valley in France.

Since then, only a few additional pieces of his skull have been found.

In a new study led by Slimak, researchers used these bone fragments to analyze Thorin’s genome and gain a clearer picture of his ancestry.

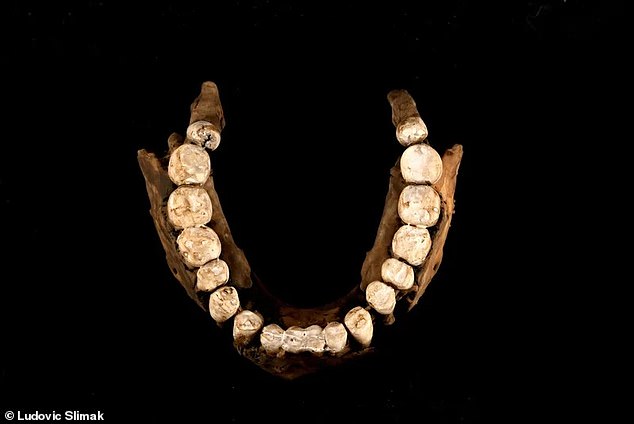

Slimak and his team performed three successive DNA extractions from the root of one of Thorin’s molars to generate a complete genome sequence.

From this, the team concluded that the remains belonged to a Neanderthal male who was part of a previously unknown lineage. Their analysis also revealed that Thorin had high ‘genetic homozygosity’, which often indicates recent inbreeding.

They published their findings Wednesday in the journal Cell genomics.

Thorin’s remains were first discovered at the entrance of a cave in France in 2015

A team of researchers used the root of one of Thorin’s molars to determine that he was male and to generate a full genome sequence

Genetic homozygosity occurs when an individual inherits the same version of a gene from both biological parents.

Furthermore, the researchers found no evidence of interbreeding with Homo sapiens, or modern humans.

The team also used several techniques, including carbon dating and assessment of the geological layers in the cave, to determine that Thorin died between 52,000 and 42,000 years ago.

But additional evidence found in 2023 suggests he likely died closer to 42,000 years ago, making him one of the last Neanderthals.

The research appears to confirm a theory Slimak put forward about 20 years ago, when he noticed differences between the stone tools found at Grotte Mandrin and those found at other modern archaeological sites.

The isolation of this Neanderthal group complicates our understanding of how these early humans disappeared and were eventually replaced by modern humans.

Like Thorin, a character from the famous book ‘The Hobbit’ by JRR Tolkien, this Neanderthal belonged to the last of his kind

Based on this observation, Slimak proposed that Thorin and his relatives were isolated from classic Neanderthal populations because they did not adopt the novel tool-making style seen elsewhere.

Now Thorin’s DNA has provided new evidence to support Slimak’s theory.

“It turns out that what I proposed 20 years ago was predictive,” Slimak said Living science in an email.

‘The people of Thorin had lived for 50 millennia without exchanging a single gene with the classic Neanderthal populations.’

The isolation of this Neanderthal group complicates our understanding of how these early humans disappeared and were eventually replaced by modern humans.

Before this discovery, scientists assumed that Neanderthals had disappeared from ancient Europe when Homo sapiens arrived on the continent between 40,000 and 45,000 years ago.

“Neanderthals were thought to be part of a single, genetically homogeneous population spread across Spain, France, Croatia, Belgium and Germany,” Slimak wrote in an article for The conversation.

For years, studies supported this theory. But the discovery and subsequent analysis of Thorin’s remains cast doubt on this story.

“Everything about the greatest extinction of humanity and our understanding of this incredible process that will lead to Homo sapiens being the sole survivor of humanity needs to be rewritten,” Slimak said.

‘How can we imagine populations that have lived in isolation for 50 millennia, when they are only two weeks’ walk apart? All processes have to be rethought.’