Large study shows that Ozempic hardly leads to fat loss

A rare study of the long-term effectiveness of obesity drugs like Ozempic suggests they may not burn as much fat as the hype claims.

Experts at the Cleveland Clinic examined the medical records of 4,000 obese people who had been prescribed various doses of semaglutide — marketed as Wegovy and Ozempic — or liraglutide, sold under the brand names Saxenda and Victoza.

On average, semaglutide led to a weight loss of 5.1 percent, compared with 2.2 percent for liraglutide after one year.

Their findings could come as a blow to the millions of Americans who expected dramatic, life-changing weight loss.

People taking semaglutide, marketed as Ozempic and Wegovy, lost more weight for at least a year than patients taking an older version, liraglutide, marketed as Saxenda and Victoza

Someone taking Ozempic who starts at 300 pounds and has a life-threateningly high BMI may only lose 15 pounds, leaving them 300 pounds overweight.

The findings offer rare insight into the long-term effectiveness of weight loss drugs, the researchers say.

These drugs have become so popular over the past three years that manufacturers and pharmacies are struggling to meet the enormous demand.

They examined medical records registered from January 1, 2015, to July 28, 2023, of 3,389 patients who had been prescribed semaglutide or liraglutide, the older version of the most popular drug Wegovy and Ozempic.

Some of the patients, with an average age of 50 and an average BMI of 38.5, were prescribed one of the drugs to treat obesity, while others were given a drug for their type 2 diabetes.

On average, patients on both drugs lost 3.7 percent of their body weight after one year.

People using semaglutide lost 5.1 percent, while liraglutide users lost 2.2 percent.

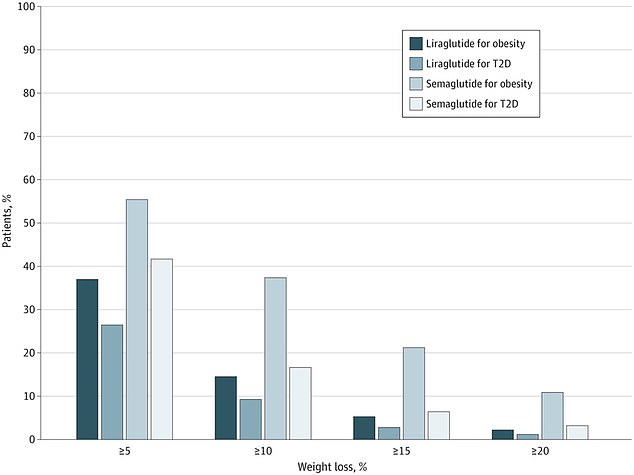

When they further broke down the results into groups, they concluded that patients taking obesity drugs lost more weight than patients taking drugs for type 2 diabetes.

People taking anti-obesity drugs often start on higher doses than people being treated for diabetes. This may have led to the striking difference in weight loss between the obese group and the type 2 diabetes group.

Patients taking anti-obesity medications were also more likely to continue taking their medications continuously for several reasons, including continued insurance coverage and a willingness to continue taking the medications long-term.

Patients taking semaglutide for obesity lost 12.9 percent of their body weight after one year, while those taking it for diabetes lost 5.9 percent.

People taking liraglutide for obesity lost 5.6 percent, while those taking it for diabetes lost 3.1 percent.

An estimated 15.5 million Americans have taken diet pills like Wegovy and Ozempic at some point in their lives in hopes of losing up to 20 percent of their body weight

Dr Shauna Levy, an obesity medicine specialist and bariatric surgeon at Tulane University who was not involved in the study, previously told DailyMail.com: ‘Obesity drugs are not a magic bullet… These are medications, they come with risks, they come with benefits, there is no one-size-fits-all solution,’ she said.

She said that people who are serious about losing weight cannot use all the weight loss medications.

The goal of the study was to determine whether people in the real world could achieve significant weight loss of 10 percent or more after long-term use.

This benchmark was chosen because research has shown that losing 10 percent of body weight can lead to significant improvements in health indicators, including a lower risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease.

Pre-approval studies of Wegovy and Ozempic estimated weight loss at five percent to 15 or 20 percent. In clinical trials for both pre-approval that lasted more than a year, patients lost at least five percent of their body weight, with an average weight loss of 15 to 20 percent

The latest findings could dash the hopes of the approximately 15 million Americans who have chosen to take semaglutide or liraglutide to lose weight.

The meteoric rise in popularity of semaglutide since 2021 has led to thousands of success stories from patients who have long struggled with obesity and its associated health effects, such as diabetes and heart disease, who have lost 20, 50, and even more than 100 pounds with the help of the drug.

The graph shows that more than a third of patients taking semaglutide for obesity lost the benchmark of 10 percent or more of body weight, compared with about 17 percent of those taking it for diabetes. About 14 percent of people taking liraglutide for obesity lost at least that much, and nine percent of those taking it for diabetes

At the same time, drugs have taken over Hollywood. There are rumors or confirmations that a long list of celebrities have taken a weight-loss drug to lose weight for a red carpet event.

This has led to millions of Americans clamoring to get their hands on these wonder drugs, creating a long-term shortage that has seen some people travel hundreds of miles to get their hands on them.

The Cleveland physicians said, “Real-world data help us better manage expectations about weight loss with GLP-1 RA medications and emphasize that persistence is essential to achieve meaningful results.”

Overall, they recorded better results in patients taking semaglutide than in patients taking liraglutide continuously for at least 90 days. Those who started with a higher BMI were also more likely to see more weight loss.

Specifically, 61 percent of patients who took semaglutide for obesity and continued taking the drug for a year lost at least 10 percent of their body weight. This is close to the results of studies in which 69 percent lost at least 10 percent.

The research was published in JAMA Network Opened.

The study’s greatest strength was its large, diverse patient population, which ensured that the individuals studied were truly representative of the broader population.

At the same time, they did not have access to other useful information about the patients, such as their diet, whether they were taking other diabetes medications, their genes and how their bodies respond to changes in glucose levels.