Neglected by my parents, abused by my uncle, then I watched helplessly as my daughter was taken from me at 19. I lived a life of utter misery – but my story proves it’s never too late to reclaim your life

At 64, Judy King sat on a psychologist’s couch, her life teetering on the brink of an epiphany.

Memories she had long kept hidden came flooding back, leaving her breathless and in tears.

For decades, the Sydney native had locked away the pain inflicted by those who should have loved her most. But as the walls of repression crumbled, a harrowing picture emerged that she could no longer ignore.

Piece by piece, Judy began to piece together her broken past, tracing her journey back to the moment she left Australia so many years earlier. What emerged was a lifetime of trauma that would destroy most: a childhood marred by abuse at the hands of her father, a teenage years shattered by her uncle’s rape, and the heartbreak of abandoning her daughter at 19. gave up for adoption at the age of 11.

“Not only did I feel worthless – I believed I was at the bottom of the ladder of humanity,” Judy says. “I was a prisoner of my own inner chaos, completely disconnected from the world and how others saw me.”

“As a child I was afraid of everything,” she continues. ‘Confidence was not only low, it was non-existent.’

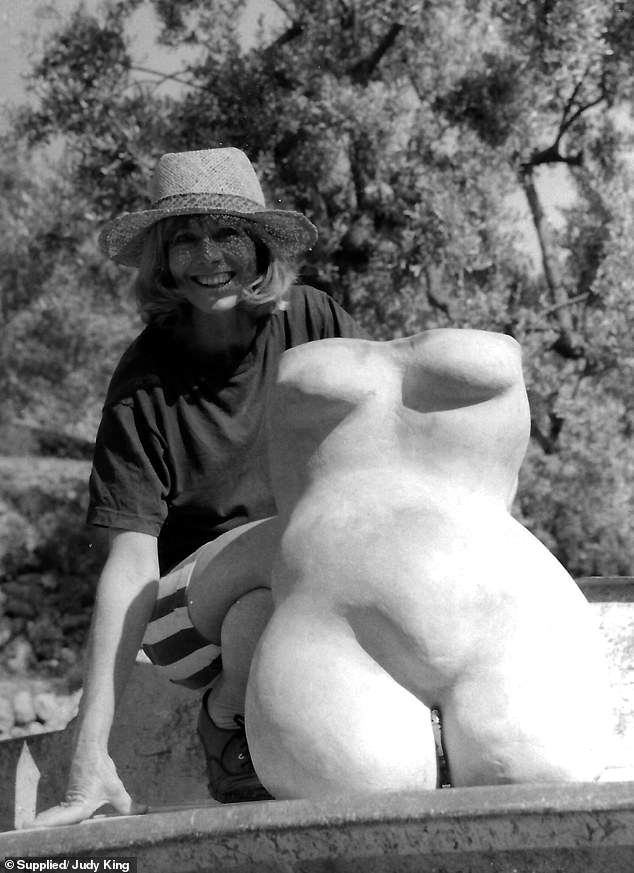

Now 82 and living in Mallorca, Spain, Judy radiates a strength forged by decades of healing. Although she misses her homeland, she is finally ready to share her story – a testament to resilience, survival and reclaiming self.

Abused as a child by her father, raped by her uncle as a teenager and then having to say goodbye to her daughter at the age of 19 – it would be enough to crush anyone. That’s what happened to Judy King (pictured left with her two brothers in an undated childhood photo)

“I thought I was on the lowest rung of the human ladder,” says Judy (pictured here in her twenties, after giving her daughter up for adoption)

As a child, Judy’s life was marked by isolation and sacrifice. While her two younger brothers were sent to boarding school, Judy was left behind, ‘sacrificed’ to stay home with her parents.

Her father, a salesman, was often away, leaving Judy at the mercy of her mother – a woman she describes as volatile and incapable.

“When Dad wasn’t around, my mother relied on me – she was pretty hopeless – but when he came home she didn’t want anything to do with me,” Judy explains.

‘She was a strange woman, very hot and cold. Looking back, she was probably a psychopath. She was never a good mother and was incredibly lazy.”

Judy remembers her mother lounging on her bed for days, adorned with expensive pearls, yet completely indifferent to the world around her. “She called me from another room to get a pack of cigarettes from her bedside table, something she could have easily done herself. She was that lazy,” Judy says.

Both of Judy’s parents were abusive and neglectful. They never picked her up from school or attended conferences, and treated her as if she were invisible.

Her mother, whom she describes as a “living disgrace,” always seemed to need help with the simplest tasks. But despite her mother’s erratic behavior, Judy still felt a deep sense of love and a need to protect her.

Growing up on Sydney’s North Shore, Judy endured horrific abuse at the hands of her father, while her mother turned a blind eye. Adding to the emotional damage, her parents labeled her with cruel labels.

‘You were always a terrible flirt. Everyone said it. You were a classifiable delinquent. Everyone thought that: your school, your grandmother, the whole family!’ they would revile.

As a child, Judy had no idea what words like “provocative” or “flirtatious” even meant, but their accusations stuck, leaving her struggling with misplaced guilt and shame.

Judy grew up on Sydney’s North Shore, where her father abused her and her mother turned a blind eye. Judy was told she was “provocative” and “flirtatious” as a child

Judy’s life took a harrowing turn when she was sent to live with her aunt and uncle in Maroubra. It was there that something completely baffling happened that would take her years – decades – to properly explain.

She became convinced that she had accidentally set the kitchen on fire – a belief her relatives denied, insisting that no such event had occurred and dismissing her as ‘crazy’.

Years later, a flashback prompted by therapy revealed the truth behind her confusion. Her uncle had taken her to the basement of his pub in Newtown, where he attacked her on an old iron bed surrounded by beer barrels. The imagined fire was her mind’s way of processing the trauma; her way of interpreting the blood and pain that she couldn’t understand at the time. Although the fire never happened, its emotional weight burned inside her for decades.

At the age of 17, Judy left Maroubra and took refuge in a retirement home in Coogee on the beach. That period was so charged that she still doesn’t quite know how she ended up there. To this day, pieces are still missing.

But the new living situation did not bring any respite. As her terrible teenage years came to an end, she became involved with an abusive and controlling boyfriend. He got her pregnant, another catastrophe.

“I was so naive that I didn’t understand how I could get pregnant by such a horrible person,” she says. “I went to the priest for confession and confided in him, even though I had committed every sin in the book.”

The priest put her in touch with a kind-hearted nun who became a lifeline in her darkest hour. “She was the first person to admire and defend me,” Judy recalls.

The nun secretly helped Judy through her pregnancy. Together they decided that Judy would give her baby up for adoption, and to protect her identity she adopted an assumed name: Catherine Johnson.

This new identity, although temporary, gave Judy a sense of escape and empowerment.

“It was thrilling and exciting,” she says. “I worked at daycare and got up at 6 a.m. to take care of the kids and change diapers before going to the office.”

Judy, now 82, began unraveling her past after seeing a psychologist at the age of 64. She has been seeing a therapist for twenty years

Amid the chaos of her life, Judy finally found a fleeting sense of stability and purpose.

After the birth of her baby daughter, Judy only had a brief moment to bond with her. If she had the chance, she would have named her Rebecca Lea.

At the age of 20, Judy worked in property and property development in Paddington, where she found solace in restoring old houses. The work became a powerful outlet for her.

“The desire to repair and restore old houses that had fallen into ruins was an external metaphor for what I wanted to happen inside me,” she reflects.

Despite the emotional burden she carried, Judy threw herself into her work. ‘I worked hard seven days a week, but I had a great time. The houses in Paddington are beautiful, and I still love them to this day. I still know the area like the back of my hand.’

In 1968, Judy’s father died of an infection that caused his throat to swell. He was rushed to Liverpool Hospital but died shortly after arrival.

A year later, at the age of 27, Judy left Australia with her future husband to explore the world. Over the years she lived in London, Kuala Lumpur, Sri Lanka and finally Mallorca.

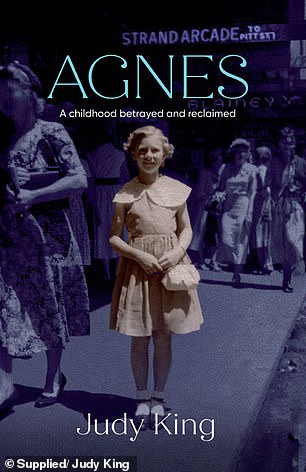

Judy put her story into words and self-published a book titled ‘Agnes, A Childhood Betrayed and Reclaimed’

Her marriage, like much of her life, was marked by pain. It lasted seven years and was abusive. Moving to Spain wasn’t Judy’s dream – it was her ex-husband’s – but she has since accepted it.

‘Relationships have never been my strong point. If you have an abusive childhood, you’re drawn to toxic people,” says Judy.

“You have no control over it; it’s like I went back to my parents in a way. You are attracted to what you know and what feels familiar.’

Judy never had the chance to meet her daughter.

After her mother’s death, Judy’s brother discovered a box of letters addressed to her, letters she didn’t know existed. Then it was too late to react.

‘My brother called me and said he had found these old letters to me, but he had no idea who they were from. He still didn’t know I had a daughter,” Judy says.

‘I didn’t know what he was talking about until I saw the letters myself. I tried my best to find her in 2006, but I couldn’t; it was impossible. To this day I have no information about her.”

Although she has made peace with the situation, Judy admits that it still weighs on her. ‘It’s always in the back of my mind. I had no choice but to give her up when I was younger because I had no money.”

These days, Judy focuses on herself – a form of self-care she never knew growing up. She no longer hates her parents. In fact, she doesn’t feel anything for them at all.

Despite the painful memories associated with Sydney, Judy has managed to reclaim the city in her own way. Seventeen years ago she returned to launch her book Agnes: A Childhood Betrayed and Reclaimed.

‘I dream about Potts Point. If I could, I would live in Australia again. Sydney is one of the most beautiful places to live and I miss it,” she says.