It is said that an ancient cloth headscarf, also called the ‘Shroud of Turin 2′, was used on Jesus’ head during his burial

Now that new research has revealed that the famous Shroud of Turin may not be a medieval forgery, new attention is being focused on other relics of Jesus’ clothing, including a relic that could “prove” the Shroud story.

Much attention has been paid this week to the Shroud’s connection to the Sweat Cloth of Oviedo, a relic kept in a Spanish cathedral that scientists have shown “matches” the face on the Shroud.

A new study by researchers in France and Italy has reexamined a groundbreaking 1988 UK investigation into the Shroud of Turin, which found that the shroud was a medieval forgery and not the cloth in which Jesus was buried, suggesting that the outcome is not definitive.

Tristan Casabianca, an independent French researcher who made the discovery, told DailyMail.com that his findings do not confirm that the shroud is older or that the burial cloth on which Jesus was buried is older.

But could other relics, including the Sweat Cloth of Oviedo, provide evidence for the life and death of Jesus? Or even prove that the Shroud of Turin is genuine?

Could other relics, including the Sweat Cloth of Oviedo, provide evidence for the life and death of Jesus? Or even prove that the Shroud of Turin is genuine?

Oviedo sweat cloth

The Sudarium of Oviedo has been called the ‘Shroud of Turin 2′. Some suggest that the markings on the cloth, which would have been wrapped around Jesus’ head when he died, suggest that it was used in conjunction with the Shroud of Turin.

This week, posters on social media emphasized how well it matches the Shroud – and that it could even prove its authenticity.

A ‘sudarium’ is a sweat cloth believed to have been placed over Jesus’ face.

The Sudarium is kept in a cathedral in Oviedo (Alamy)

The sweat cloth is kept in a cathedral in Oviedo. Unlike the Shroud of Turin, there is no clear face visible, but there are noticeable stains.

In John chapter 20, verses six and seven, the Bible says, ‘And Simon Peter followed him, and went up also. And when he came to the tomb, he saw the linen cloth lying on the ground, and the cloth that had been upon his head. And the cloth was not with the linen cloth, but was rolled up in a place by itself.’

The history of the cloth was recorded by a 12th century bishop. He claimed that it was in Palestine until 614 AD, when it was taken from Jerusalem and given to the bishop of Seville.

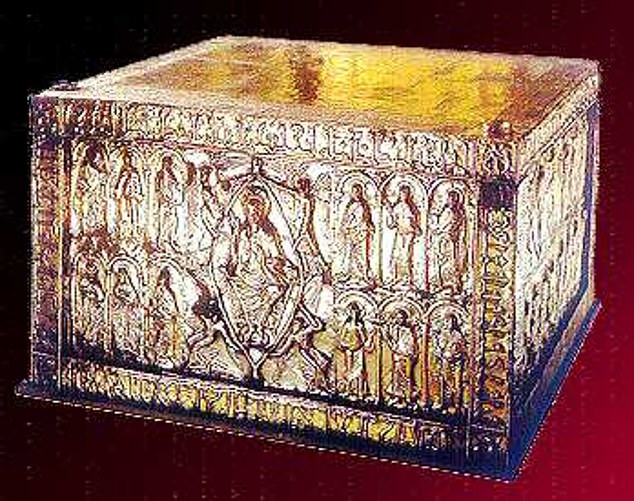

The sweat cloth is located in the Arca Santa, an elaborate reliquary

The sweat cloth contains several details that indicate it may have covered the same face as the Shroud of Turin.

Although there is no face visible on the sweat cloth, the stains do provide clues as to the person whose face it covered. It appears that he died in a position similar to that of a crucifixion.

The blood group is the same (AB) and the length of the nose of the person whose face is covered with the sweat cloth is the same as that of the Shroud of Turin.

In 1984, Dr. Alan Whanger of Duke University used a polarized overlay technique to compare the two.

Whanger said: ‘We have noted approximately 130 points of similarity between the shroud and the washcloth. We feel this is strong evidence that both were in contact with the same person.’

The Sudarium is said to date from the 9th century, but there are also older references to it.

Carbon dating showed the species emerged around 700 AD, but researcher Cesar Barta suggested it could have been caused by oil contamination, as there are references to its presence in Jerusalem in 570 AD.

The Image of Edessa

Other icons depicting the face of Jesus are said not to have been made by hand, but to have been miraculously imprinted.

But could one of these objects actually be the Shroud of Turin, and could it reveal where it lay in previous centuries?

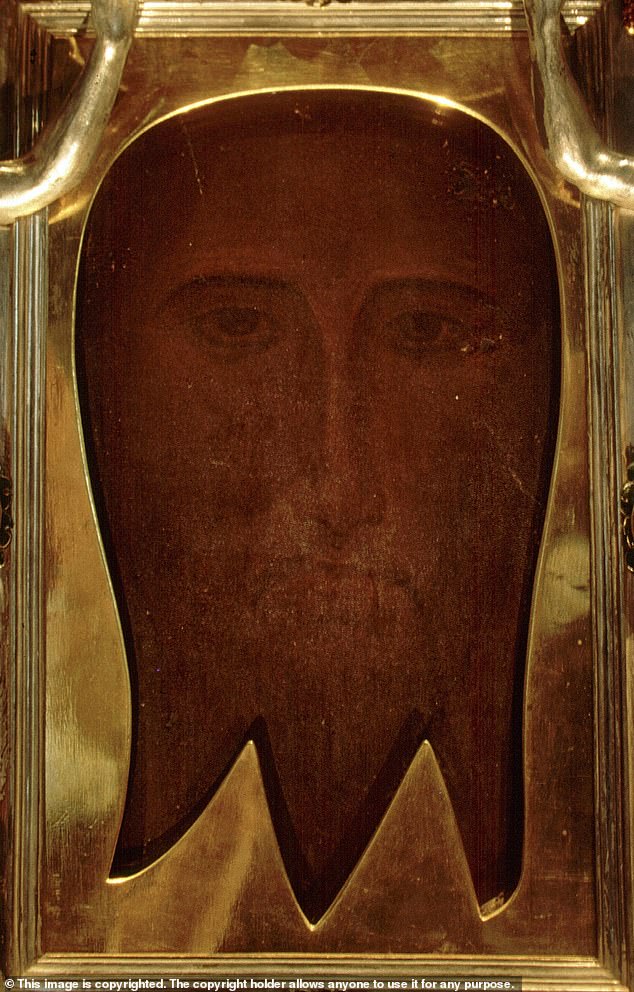

The Mandylion of Edessa from the Pope’s private chapel in the Vatican

Author Ian Wilson suggested that the Image of Edessa, also known as the Mandylion and first mentioned in the fourth century, was actually the shroud folded four times.

The image of Edessa is said to have come from an ancient king, King Abgar of Edessa, who asked Jesus to heal him of an illness.

Jesus refused, but a letter was sent that was supposed to be from Jesus. In it an image was painted or made by God.

Some claim that the image venerated as the Image of Edessa was in fact the Shroud of Turin.

The Holy Coat

In John 19:24 the Bible tells us that at the crucifixion of Jesus the soldiers said to one another, “Let us not tear it, but cast lots for it, whose it shall be.”

Several churches in Europe claim to have the Holy Coat (or seamless vestment) itself, or parts of it, in their possession.

The collarless neck of Jesus’ seamless robe

In Argenteuil (France), parts of the vestment, said to have been given to Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor, in 800, are preserved in the church.

The robe was preserved until the French Revolution, when a parish priest cut it into smaller pieces for fear that it would be destroyed.

Veil of Veronica

The Veil of Veronica is displayed in Vatican City during Lent. Believers claim it bears the image of Jesus’ face, after a woman named Veronica wiped his face with a cloth.

Believers claim it bears the image of Jesus’ face after a woman named Veronica wiped his face with a cloth

The chapel is protected by the Vatican and dates back to the 14th century. Pope Innocent II wrote a prayer in honor of the chapel in 1207. However, a ‘Veronica Chapel’ already existed during the reign of Pope John VII (705-708).

The image is supposed to show a face with a beard, but during Lent only the frame is visible.