Is YOUR child picky? It’s in their genes! Picky eating is a ‘largely genetic trait’ and lasts from toddlerhood to early adolescence, research shows

For many parents, ensuring their children eat enough fruits and vegetables is a daily struggle.

But if your child is picky about what he or she eats, there’s no reason to blame your parenting skills, according to a new study.

Scientists from University College London (UCL) studied the food preferences of more than 2,400 pairs of identical and fraternal twins.

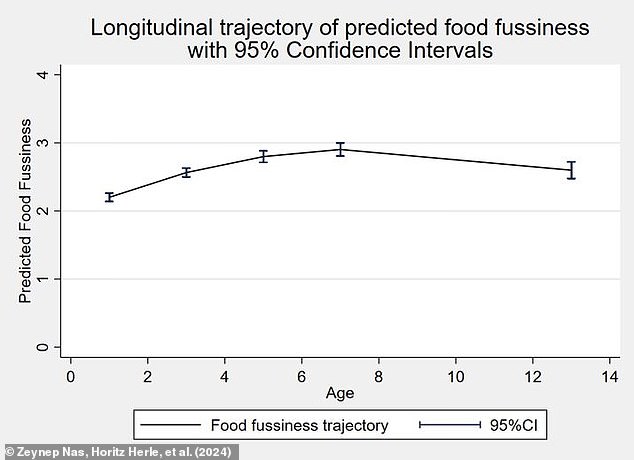

Their findings show that genes determine 60 percent of how picky a 16-month-old is.

And the role of genetics becomes even greater as children get older: between the ages of three and 13, genetics accounts for 74 percent of irritability.

For many parents, getting your kids to eat enough fruits and vegetables can be a daily struggle. But if your child is picky about what he or she eats, a new study suggests there’s no reason to blame your parenting skills (stock image)

While DNA plays an important role in picky eating, that doesn’t mean parents should give up on their efforts to encourage healthy eating, the authors say.

Fussy eating is defined as the tendency to eat a small variety of foods, because of texture or taste, and a resistance to trying new foods.

Lead author Dr Zeynep Nas from University College London said: ‘Fussy eating is common in children and can be a huge source of anxiety for parents and carers, often blaming themselves or others for this behaviour.

‘We hope that our finding that picky eating is largely innate can help alleviate some of the guilt parents feel about this behavior. It is not a result of parenting.

‘Our research also shows that picky eating is not necessarily a ‘phase’ but can follow an ongoing pattern.’

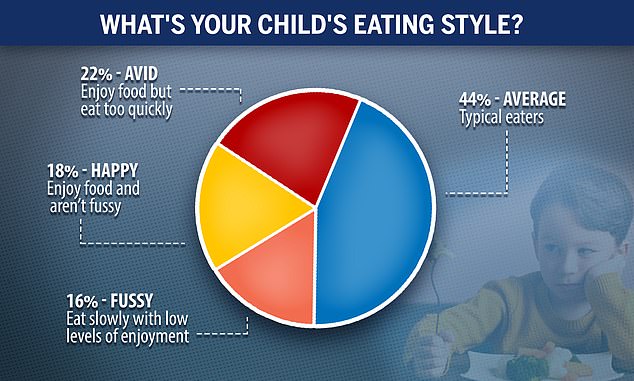

Previous research has found that only 16 percent of children are considered “picky,” while the remaining 84 percent are “avid,” “happy” or “typical” eaters, they say.

Lead author Professor Clare Llewellyn from UCL said: ‘While genetic factors have the biggest influence on choosiness, environment also plays a supporting role.

‘Shared environmental factors, such as sitting down to eat together as a family, may only be important in toddlerhood. This suggests that interventions to help children eat a wider range of foods, such as exposing children to the same foods regularly and offering a variety of fruits and vegetables, may be most effective in the very early years.’

In the study, parents of twins completed questionnaires about their children’s eating behavior when the children were 16 months, three, five, seven, and 13 years old.

They found that fraternal twins showed greater differences in picky eating habits than identical twins, suggesting a strong genetic influence.

Identical twins have identical DNA, while fraternal twins have only 50 percent of their DNA in common.

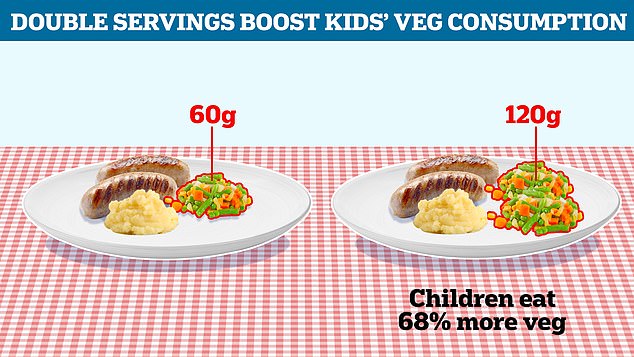

If you’re still struggling to get kids to eat vegetables, previous studies have shown that doubling the portion size leads to a 68 percent increase in vegetables eaten

The researchers found that pickiness tended to peak at age seven, before gradually declining, as seen in this graph of pickiness versus age. The study also found that children who were more picky in earlier years tended to have a higher peak in pickiness, but also a sharper decline between the ages of seven and 13.

The team also found that identical twins became less similar in their picky eating behavior as they got older, suggesting that unique environmental factors play a greater role in old age.

Lead author Dr Alison Fildes from the University of Leeds said: ‘Although picky eating behaviour has a strong genetic component and can extend beyond early childhood, this does not mean it is a fixed fact of life.

‘Parents can continue to encourage their children to eat a varied diet throughout childhood and adolescence, but peers and friends can have a greater influence on children’s diets as they become teenagers.’

According to the authors, a limitation of the study is that a large proportion of households in White, British households come from wealthier backgrounds.

According to the team, future research should focus on non-Western populations, where food cultures, parental dietary habits and food security may be very different.