Is it ever worth paying a performance fee on your investments?

Performance fees have long been a controversial part of the investment industry.

Some see them as over-rewarding fund managers for good performance while not sharing the pain of poor performance with investors.

Historically, these costs have been common in the areas of private equity and absolute return funds.

They are also more common in investment trusts, but a few funds have them as well.

We weigh up whether it’s worth paying a performance fee and ask if there are any regions where it might be worth it.

Keep an eye on that performance fee: the question is whether it motivates fund managers to generate higher returns for investors

What is a performance fee?

A performance fee is a payment to an investment manager for generating positive returns. This is different from a management fee, which is charged regardless of the return.

The idea behind performance fees is that they should motivate fund managers to generate higher returns for investors. But there are questions about whether they really do this.

Details about performance fees can often be found in documents such as fact sheets and reports and accounts.

Investment company performance fees are also typically detailed in the “Fees” section of a particular company’s page on the Association of Investment Companies website.

When can a performance fee pay off?

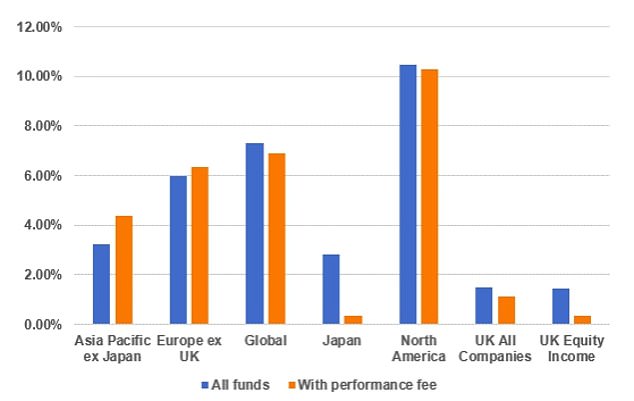

Research by asset manager RBC Brewin Dolphin into long-only equity funds (which only buy shares rather than short selling) has shown that funds with performance fees attached to them have in most cases underperformed their respective markets.

The average annualized returns of global, Japanese, North American, UK companies and UK performance fee equity funds failed to keep pace with their peers.

The largest performance gap was Japan. Funds with performance-related fees delivered an average annual return of just 0.34 percent, compared with 2.81 percent for all 66 Japanese funds.

But the analysis also shows that performance fees may be worthwhile in certain regions.

This was the case in Asia-Pacific, excluding Japan, and in mainland Europe.

Asia-Pacific performance fee funds delivered an average annualized return of 4.37 percent, compared to a sector average of 3.22 percent, while European performance fee funds returned an average of 6.37 percent, compared to 5.96 percent for the total market.

Rob Burgeman, senior investment manager at RBC Brewin Dolphin, says: ‘There are certain regions where it is worth considering performance fee funds, and others where it is not.

‘In markets like North America, it is notoriously difficult to consistently outperform benchmark indices, which is one reason why so few people bother to charge a fee and passive indexes have grown in popularity.’

five-year average annual returns of long-only funds. Source: RBC Brewin Dolphin

Do you have to pay for performance?

When it comes to investing in performance fee funds, you need to know what you are paying for.

An important question when considering investing in a fund with a performance fee is: does the fund offer anything different than a fund without a performance fee?

James Yardley, senior research analyst at Chelsea Financial Services, advises investors to ask themselves the following questions: ‘Are there other good or better competitive funds available without performance fees?

‘If a fund charges a performance fee, you have to ask, “Why?” What do you actually get as an investor? There may be some benefits, such as lower annual management fees.

Burgeman says: ‘A performance fee should only really be considered if there are specific strategies or if the fund offers exposure to specialist areas.

‘In those cases it can even be a good thing to align the interests of managers and investors. The other side of the coin is that it can also encourage managers to take excessive risks if the right checks and balances are not in place.”

The experts we spoke to were critical of performance fees, and some would like to see them disappear.

Yardley says: ‘With so many active and passive funds available, the bar is high in my opinion to justify a performance fee in today’s market. So in general I’m not a big fan of performance fees, but in some cases that can be fine.

Ryan Hughes, Head of Investment Partnerships at AJ Bell, said: ‘Broadly speaking, I believe performance fees have little place in retail investment funds.

‘I suspect many will argue that the typical 0.75 to 1 percent fee that asset managers can earn is enough to run a highly profitable business, without the additional performance fee on top.

‘With so much choice in the world of low-cost passive investments, paying a performance fee on top of an annual management fee will require an investment to work hard to justify its value.

‘Sometimes it can simply be worth it, especially in asset classes that are very difficult to access, such as private equity, but in mainstream equity and fixed income funds it is becoming increasingly difficult to stomach.

When it comes to performance fees, there should be a high watermark.

Burgeman says: ‘There absolutely needs to be a high watermark – in other words, the fund’s returns must meet the performance threshold over a period of time, so any underperformance must first be recouped before a performance fee is charged – or it’s simply not worth it.

Are performance fees fair?

Ryan Hughes, AJ Bell says: ‘With the advent of primarily value assessment, and now, more recently, consumer duty, the justification of performance fees is becoming more difficult in products designed for retail investors.

‘I suspect this is an area that the FCA will want to keep a close eye on to ensure that asset managers explain fees clearly to investors and then ensure they remain at a reasonable level.

‘Under the new rules, these fees will have to be clearly justified, with the responsibility of asset managers to do so.

‘Currently, the calculation methodology is often hidden away in the prospectus and written in a way that is very difficult to understand.

‘Hopefully the new rules will improve transparency, but perhaps more importantly, eliminate them from retail-focused funds altogether.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.