Inside the world’s first nuclear waste ‘tomb’ costing $4 BILLION

The first ever ‘grave’ for nuclear waste, located nearly 1,500 feet below the surface, will soon be sealed off from humans to safely decompose for 100,000 years.

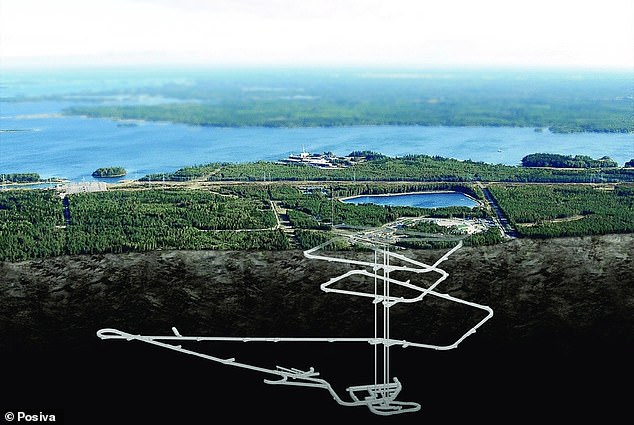

Finland’s $4 billion Onkalo project consists of a ten-mile network of underground tunnels designed to store the country’s 6,500 tons of uranium waste generated by a nearby nuclear power plant.

The country is a leader in nuclear energy, with its reactors having an average lifetime capacity of more than 90 percent.

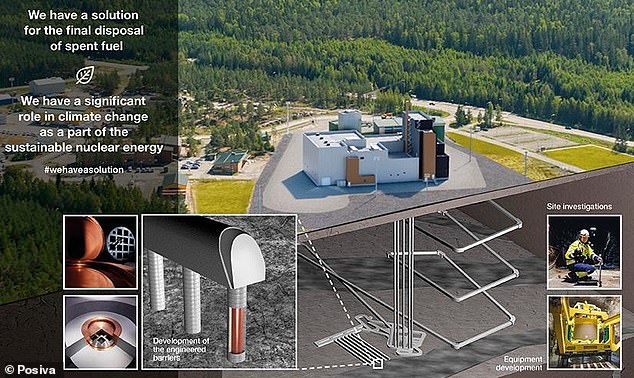

Finnish waste management organization Posiva launched the initiative in 2019, explaining that nuclear waste would be stored in waterproof canisters.

By 2026, Posiva plans to bury 3,250 copper waste containers, each 5 meters long and containing about two tons of spent reactor fuel.

The canisters are transported to 70 meter long deposition tunnels and surrounded by bentonite clay for permanent storage.

They are then all lowered into a vertical borehole in the repository’s disposal tunnels, each containing approximately 30 to 40 boreholes.

Once all boreholes in a tunnel have been filled with bushings and insulated with bentonite clay buffers, the tunnels are filled with clay and sealed.

Finland’s $4 billion Onkalo project is located on Olkiluoto Island

The underground facility features six miles of tunnels, which will soon be home to the 6,500 tons of uranium released by a nearby nuclear power plant.

The fuel, which contains plutonium and other nuclear fission byproducts, will remain radioactive for tens of thousands of years.

However, encased in two-inch-thick copper, surrounded by bentonite clay and embedded in ancient granite, the waste poses no risk of contamination to future generations, according to Posiva.

Originally a research facility, Onkalo became the first nuclear waste repository of its kind after Posiva proposed using it to permanently house highly radioactive material.

“Many countries using nuclear energy have facilities for the final disposal of low- and medium-level waste, but the final disposal of high-level spent fuel has not yet started anywhere,” Posiva said on its website.

Currently, spent fuel is typically stored in large, secure tanks in dedicated facilities.

Another method involves encasing the waste in glass and burying it about 500 feet underground, a process known as Deep Geological Disposal.

Although effective, this method carries risks due to long time scales and the potential for unforeseen geological changes that could compromise containment for thousands of years.

Posiva claimed that the tunnel system and containers are designed to withstand earthquakes, future ice ages up to a million years and stress caused by continental ice.

For more than forty years, Posiva studied and tested the rock near the Olkiluoto nuclear power plant to ensure that even if one or more containment barriers failed, no radiation would seep into the environment.

Onkalo consists of a spiral access tunnel, vertical shafts, central tunnels, end storage areas, technical areas, welfare facilities and even a café-canteen for staff.

Posiva, a waste management organization, built a tunnel to house spent fuel to prevent radioactive material from harming the environment

The containers are lowered into a vertical borehole in the repository’s disposal tunnels, which have approximately 30 to 40 holes.

When all holes contain a bushing and the bushings are insulated with bentonite clay buffers, the entire tunnel is filled with clay and sealed

The tunnels are too narrow to take the buses to final storage, so they are taken to a service area using a lift from an encapsulation facility on the surface where the buses with spent fuel reside until they are ready to go into the tunnel are placed. .

The canisters are then picked up by robotic vehicles and taken to deposit holes in an area where they will be stored for the next 4,000 generations.

At the time the spent fuel is recovered, Posiva said only one-thousandth of the original radiation levels will remain, but this small amount is still highly radioactive.

“A small portion of the radioactive materials in the fuel have extremely long lifetimes, which necessitates their isolation from nature,” Posiva said.

‘For this reason, the final storage containers are designed to remain tight and impermeable at their final disposal site long enough for the radioactivity of spent fuel to decline to a level that is not harmful to the environment.’

The tunnel is located 450 meters underground on the west coast of Finland and will be closed for 100,000 years from 2025

The bushings are made of copper and are filled with bentonite to prevent it from entering the surrounding rock

The copper and cast iron bushings will be wrapped in bentonite clay and deposited in 1,410 feet of 1,800-year-old rock – also known as a natural release barrier.

The organization said that even after the first tunnel is closed next year, it will continue to expand and excavate more deposition areas and central tunnels, allowing final recovery operations to continue until the 2120s.

When each tunnel is completed and filled with spent fuel, it is closed and when final disposal has taken place, the access connections to ground level, including the vehicle tunnel, shafts and test holes, are closed.

The researchers explained that radiation levels will decrease to one-hundredth of their original amount within the first year.

The researchers tested the final disposal starting in 2019, when two containers were installed in deposition holes deep in the tunnel.

Each hole is separated by bedrock and is approximately 26 meters deep and 1.7 meters in diameter.

It was filled with bentonite – a soft, plastic clay formed from volcanic ash and sedimentary rock – and closed with a concrete plug.

Posiva built a facility above the tunnels to store the spent fuel bottles and will then deposit them into the tunnels via elevator

Researchers then activated 500 sensors that checked whether the radioactive material seeped into the rock.

The bedrock in the final Olkuluoto disposal area was thoroughly studied to look for weak zones, chemically unstable sections and water flow pathways that would transport radioactive material to the surface.

Their findings showed that the material would not harm the environment if placed on the bus, prompting the company to begin construction of the tunnels the following year.

Posiva began its final test on August 30 to confirm the tunnel was ready for permanent removal, saying at the time that it would take several months to complete the entire process.

DailyMail.com has contacted Posiva for comment and to confirm the official date when the tunnel will be closed.