I was locked in a room for seven days because I was on my period

Sumina Kumal was 12 years old when she got her first menstruation at a relative’s house.

At her mother’s insistence, Sumina isolated herself in a room for days, afraid of what the neighbors would think if she let her daughter run free.

And for three days she sat there.

“I wasn’t allowed to go outside to see the sun, and it was winter. I just couldn’t stand it, so I defied my mother and went outside to see the sunlight.”

Sumina has now learned to cope with the isolation by viewing it as “three days of rest” and she “dissociates” from the idea that her parents insist on following such a practice.

But this is not an isolated incident.

Sumina Kumal was only 12 years old when she was first isolated in a room for days during her menstruation

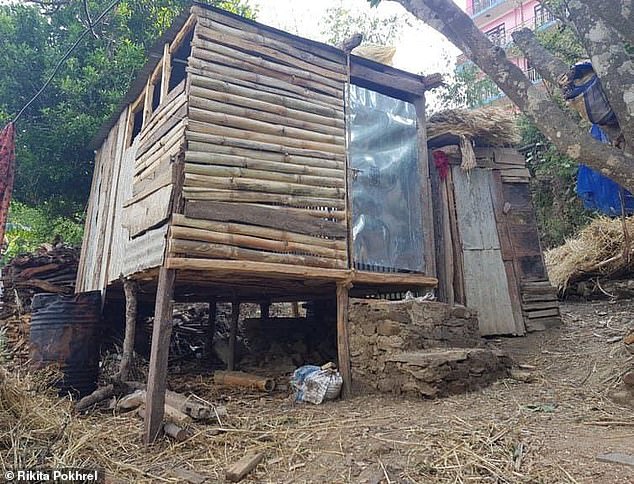

These menstrual huts are usually made of mud or wood and are located kilometers away from the main building.

It is a Nepalese cultural custom known as Chhaupadi – a menstrual taboo that prohibits women and girls from participating in normal daily activities during their menstrual cycle.

I traveled to Nepal and was shocked by the reality these women and girls face.

Getting your period means you have the potential to create new life and is seen as your emergence into womanhood. But menstruation in Nepal has long been associated with being morally corrupt and evil.

Rikita Pokhrel, 19, said she was isolated in a corner of a room for seven days during her first period.

She had to sleep on the floor with a separate sheet and had to adhere to strict rules outside of confinement.

Rikita told FEMAIL: ‘For the first three days, we are not allowed to enter the kitchen, cook meals for our family or touch the meals that have been prepared. We are also not allowed to go to the temple.’

Menstruating women and girls are seen as the manifestation of bodily impurity. It is also widely believed that contact with a menstruating woman can contaminate food, people and religious icons.

The rule of a Kumari, who is personally selected around the age of three or four, is symbolic of this practice.

Rikita Pokhrel said she wants to break the taboos surrounding menstruation and study psychology. She also wants to fight against strict curfews and gender discrimination.

I visited one of the Kumaris’ palaces twice. Both times I was astonished by the reverence shown to her and the composed look on such a childish face.

Kumaris are selected after a series of tests – one of which involves achieving 32 physical perfections, such as having ‘the chest of a lion’ – before being sent to the various palaces, known as Kumari Ghar, to become the living incarnation of the Hindu goddess Taleju.

When I was in Kathmandu, I saw the Kumari twice. She was a young girl with a painted face, adorned with jewelry and beautiful clothes.

She stood on the balcony with a deadpan expression as we bowed to her and said ‘namaste’. After 20 seconds she ducked inside and we were escorted out of the palace, the door locked behind us.

Every physical action the Kumari takes is interpreted as an omen. If she smiles at you, it means you will die soon. If her feet touch the ground outside the temple, it means an earthquake is coming.

That power is literal and they treat her with the utmost awe, offering the living goddess a life of luxury.

Until her first period.

When she bleeds, it is believed that the goddess leaves her body and she is banished from the temple with the expectation that she will live the rest of her life as a nun. The Kumari’s family receives compensation equivalent to $80,000 to $90,000.

Rama Rama, a Nepalese guide at Kathmandu’s Basantapur Durbar Square, where one of the nine Nepalese Kumaris lives, said: ‘She is a spiritual guru, a spiritual tutor. They remove the obstacles of life, but only before her period. After her period, she loses her Goddess powers.’

I met Rikita, Rejina and Sumina during a panel for the Girls Empowerment Program in Nawalpur, Nepal

Tourists have the opportunity to see the Kumari at Kathmandu Basantapur Durbar Square, but after she appeared, we were led out of the palace square and the doors were locked behind us with a chain.

When I asked him why menstruation is considered impure, Rama Rama said, ‘It is natural. Before menstruation, women are innocent. It represents the Earth and the Earth is virgin, so it is a virgin power. A supernatural power.’

Menstrual taboos are passed down from generation to generation, especially by grandmothers and mothers who experienced the same rules.

Rikita said, ‘They are women who come to me and say this is our tradition. These are our rules. This is what our ancestors gave us. So you have to follow this.’

On a night out in Kathmandu, I met Yozana Thapa, a female comedienne who told me that she often uses the discrimination women experience in Nepal in her sets.

According to Yozana, her generation is leading the way in breaking the stigma surrounding menstruation, but it is often difficult to change the minds of older generations.

“It’s hard to convince your family. At some point you just give up because they’re not going to change anyway, so I just wait until they die.”

Chhaupadi is enforced by the community. If it is known to the neighbourhood at religious places and temples that a woman who visits there is menstruating, they are ostracised and ridiculed.

Rikita said, ‘People will talk badly behind your back or challenge you in the crowd. When society finds out, they will ask what will happen to this generation? What will they learn from our ancestors?

“They’ll say she’s a leader. She’s doing bad things. They’ll try to stop your growth, or they’ll stop everything the girl has done or what she’s doing with her life.”

The Girls Empowerment Program is currently building a center in Nawalpur

Girls in Nepal have died in ancient menstrual huts from snake bites, overheating, hypothermia and animal attacks

Some girls have been successful in dismantling Chhaupadi. Women’s advocate Rejina Gharti, 20, said: ‘I first tried to break this stigma in my own home before I started advocating in the society and community so that I could reach out to other people.’

In Rejina’s house, she told me that she has free rein in the kitchen and is not forced to isolate herself. The only barrier to entry is the temple.

During Tihal in Nepal, a five-day Hindu festival in late October, Rejina used her homemade sanitary napkin to hide her period from her mother.

But on the second day she continued to bleed.

‘When I said I was taking a bath because I was bleeding, my mother said, “Oh, then you can’t give Tikka to your brothers. You can’t celebrate the festival.”‘

Rejina responded with the only secret she knew: in Nepal, you are allowed to pray in the temple on the seventh day of a woman’s menstrual cycle.

Rikita used scientific evidence to debunk stigmas surrounding menstruation within her family.

There is a belief throughout the country that if a menstruating woman touches a plant or vegetable, it will rot. So she decided to conduct an experiment with flowers on the second day of her mother’s menstruation.

During my last few days in Nepal I met Rejina at another organization. She was in the process of applying for a visa to travel to a conference in Bangkok to pitch business ideas on making sustainable clothing from hay.

Most girls in Nepal do not stay in menstrual huts and are therefore locked in their rooms or have to stay with a relative to avoid seeing their fathers and brothers.

Rikita was 16 years old when they went to their garden to plant the flowers they bought at the market. After a few days, Rikita’s flowers died while her mother’s flowers bloomed.

Rikita showed her grandmother her mother’s flowers and received a surprising reaction.

“I don’t know what happened that day, but when my grandmother saw the results of the experiment, she started to show some support. She understood what I was trying to tell her.”

Rikita said that after that day, she was given the freedom to move around her household again, before the seven-day restrictions were over.

‘I can go wherever I want, I can talk to my parents and even eat whatever I want.’

Rikita, Yozana, Rejina and Sumina have all indicated that they will not continue this practice with their children.

Rikita said, “Menstrual taboos are not the only things we need to change. There are so many things in our society that we need to work on. So I will push for that in the future.”