I got colon cancer when I was 36 – and 200,000 others have the same risky gene as me. But there IS an answer and a daily pill that can help… if you know what you’re looking for

Learning that she had advanced bowel cancer at the age of 36 understandably came as a devastating shock to Carla Mitchell – not least because the disease is normally associated with people in their 60s and over.

What the Kent marketing rep didn’t know at the time was that she had been born with Lynch syndrome – a recognized genetic condition that affects up to 200,000 Britons and significantly increases their risk of numerous cancers at a young age.

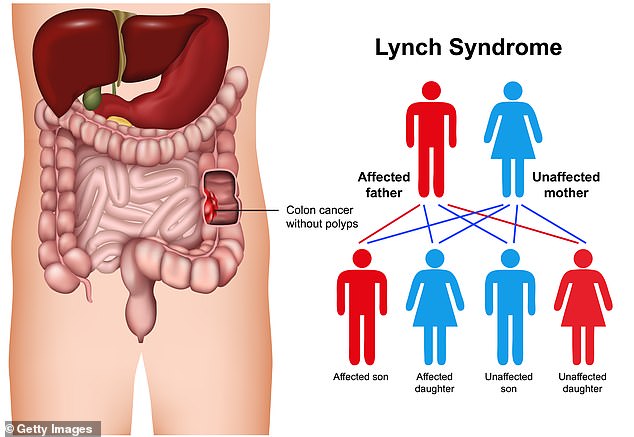

Those with Lynch syndrome have mutations in one of four genes – MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 – that normally help repair DNA errors in cells. The mutations instead mean that cells are more likely to develop into cancer.

As a result, they have a more than 70 percent greater risk of cancer affecting the bowel, uterus, ovaries, stomach, gallbladder, prostate and urinary tract, according to Cancer Research UK.

Lynch can run in families – so first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) of someone with Lynch have a 50 percent risk of having the genes themselves. But if the condition is diagnosed early in life – through genetic screening – carriers can receive advice to help reduce their risk.

For example, taking a low dose of aspirin daily could reduce the risk of colon cancer by 40 percent by reducing the inflammation that causes healthy intestinal cells to become cancerous.

Yet NHS figures show that 95 per cent of Lynch carriers are unaware of their genetic risk of cancer – and only 5 per cent have been identified.

This is despite the fact that gene screening tools for Lynch are available in the UK – and official NHS policy is to screen all bowel cancer patients for the condition (but recent studies show this has been done only piecemeal) .

Now there is more impetus to find people with the syndrome, after the NHS launched a national bowel screening program earlier this year.

Carla’s devastating diagnosis came out of the blue in 2021.

‘Looking back, there were red flags: I was unusually tired, but it was the end of lockdown so I put that down to being less physically active and my hectic work schedule.

‘But it wasn’t a kind of fatigue I’d experienced before; I felt heavy and my legs ached. When I tried to run upstairs, my heart would race.”

A blood test by her doctor showed that her iron levels were low. She was told she was “dangerously anemic and needed to go to hospital.”

‘It made me panic. “I had never been to the hospital,” she said. She was given iron infusions and underwent further tests.

Carla Mitchell was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2021 at the age of 36

Days later, on Christmas Eve 2020, her GP called to say they had found blood in her stool and that she urgently needed a colonoscopy (an examination of the bowel with a camera).

Within weeks, Carla was diagnosed with stage 3 colon cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes. She had surgery to remove the tumor, followed by three months of chemotherapy. When her treatment ended in August 2021, a scan found no evidence of cancer.

Only then did someone mention the possibility of genetic testing for Lynch syndrome.

“Six months later I received a letter from the genetics team at Guy’s Hospital saying I had a form of Lynch (a mutation in the PMS2 gene),” Carla recalls.

‘I didn’t take the news well; it was harder than being diagnosed with cancer. Lynch means there’s always a cloud hanging over my head.’

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommended in 2017 that everyone diagnosed with bowel cancer should be tested for the syndrome.

But a February report from NHS England’s National Disease Registration Service, published in the European Journal of Human Genetics, warned that these guidelines were not being implemented, and as a result doctors were failing to treat up to 700 people a year with to track down Lynch.

Experts believe that women with endometrial (or uterine) cancer, another disease linked to genes, should also be screened.

“For many women with Lynch, endometrial cancer is the first cancer they develop,” Clare Turnbull, professor of translational cancer genetics at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, told the Mail.

But a study she co-authored, published in October in the BMJ Journal of Medical Genetics, found that in England in 2019, only one in eight patients with Lynch syndrome were diagnosed through screening of endometrial cancer cases.

Lynch syndrome significantly increases the risk of numerous forms of cancer at a young age

Professor Turnbull says if Lynch patients are made aware of their genetic danger, they could benefit from strategies to significantly reduce their risk of fatal cancers.

Some experts advise women with Lynch to have their ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus removed as soon as they become pregnant, for example to protect against endometrial cancer.

Professor Turnbull says greater efforts are also needed to trace the relatives of those affected, as they may have the condition but are unaware of it.

Meanwhile, NICE recommends that people with Lynch should also have a colonoscopy every two years to check for signs of bowel cancer.

But it brings many difficulties, says Professor Turnbull.

‘Many of these cancers are not easy to recognize. For example, they do not stand out from the colon tissue like polyps, as normal colon cancers do. A lot of them are flat and hiding,” she says.

But Naser Turabi, director of evidence and implementation at Cancer Research UK, insists screening is ‘extremely effective’ in detecting cancer at an early stage.

However, he admits that colonoscopies for people with Lynch need to be more thorough than usual because doctors are “looking for something that often doesn’t cause symptoms.”

In February, NHS England announced a world first: routine bowel cancer screening every two years for those known to have Lynch syndrome, identified through family or because they have already had cancer.

The problem is that this only covers the 10,000 people in England who are already on the NHS Lynch syndrome register – and not the approximately 190,000 who have not yet been diagnosed.

But NHS England says this coverage will improve as genetic screening spreads. For example, it says that 94 percent of people diagnosed with colon or endometrial cancer in 2021 through last year were tested for Lynch syndrome – up from just 47 percent in 2019.

But questions remain about how effectively the biennial screening is being implemented, Mr Turabi said.

“There is a lot of pressure on genomic services,” he says. “And Lynch tests are not as urgent as, say, gene tests for lung cancer, where they would help doctors determine what specific treatment a patient should receive for their specific form of the disease.”

Meanwhile, the need to identify more people with Lynch is becoming increasingly important as scientists at the University of Oxford work on a vaccine that could prevent them from developing cancer.

One of the researchers, Dr. David Church, a clinical scientist and a doctor specializing in oncology, said the vaccine will help patients’ immune systems detect cells that become carcinogenic due to DNA errors in Lynch syndrome.

‘As the cells multiply, they disable the protein mechanisms by which the immune system recognizes them, effectively cloaking themselves.’

The hope is that a jab will ‘turbo-charge’ patients’ immune defenses so they can kill malignant cells before they go undercover.

Another line of attack is through the UK’s National Lynch Syndrome Registry, a new database of Lynch patients – which will match patients’ DNA data with their cancer diagnosis, treatment and outcomes, in the hope that this will help doctors find the most effective treatment and prevention strategies.

Meanwhile, Carla’s mother undergoes the gene testing process – as Carla, who does not know her father, explains: ‘we don’t know of cancer in the family, although you can have the mutation and never get cancer’.

She and her husband Simon want children and are considering their options – especially as she has been advised to have a hysterectomy at the age of 45 to prevent endometrial cancer.

“If we have a child naturally, there’s a 50/50 chance they’ll have Lynch,” she says.

‘With IVF we could have embryos screened to remove any embryos with the Lynch mutation. But IVF can take years.’

But Carla remains resolutely positive.

“I am confident that there is a future for people with Lynch,” she says.

‘Even if my child were to get it, I am confident that modern medicine will ensure they have a healthy future.’