How smoking cannabis as a teenager can make you stupid, according to new research among 12,000 adolescents

- Teens who had used cannabis in the past year had worse episodic memory

- There were no significant differences between the groups at age 9-10 years

- READ MORE: Daily pot smokers have up to a 60% higher risk of these problems

Smoking cannabis as a teenager can affect your memory and learning skills – both crucial indicators of intelligence, a study has suggested.

Researchers from the University of California, San Diego found that adolescents aged 13 to 14 who had used cannabis in the past year had worse memory than those who had never used the drug.

The study used data from the Adolescent Brian Cognitive Development study, which follows 12,000 youth in the US from ages 9 to 10 through late adolescence.

Researchers looked at a subset of participants who had hair samples taken when they were about 13 to 14 years old.

And participants underwent a full cognitive assessment every year.

The researchers found that teens who used cannabis performed worse on tests measuring memory and experienced a decline in understanding words and sentences.

Research shows that smoking cannabis as a teenager can impair cognitive function

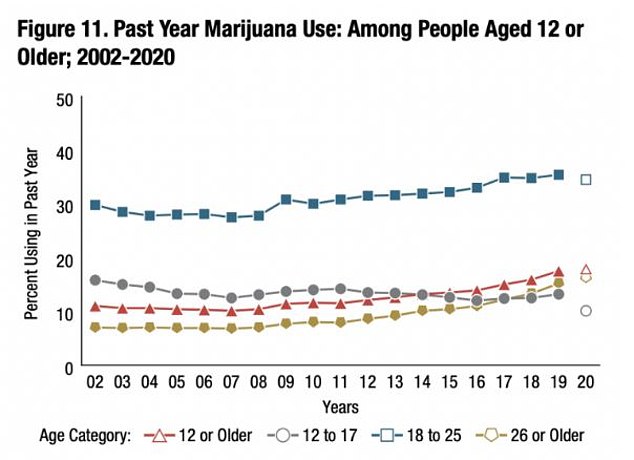

Marijuana use increased among all age groups between 2002 and 2020, according to the graph above

For the study, hair samples were taken from test subjects and analyzed for three substances in cannabis; THC, THCCOOH and cannabidiol (CBD).

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the plant’s main psychoactive element, produces a person’s high. It acts on the cannabinoid receptors in the brain and is thought to increase the risk of psychosis and other mental illnesses by disrupting parts of the brain responsible for processing information and behavior.

THCCOOH is a substance that is produced by the body from THC and that remains in the body longer than THC.

cannabidiol (CBD) is a non-intoxicating compound found in marijuana and hemp.

Hair samples were combined with self-reported cannabis use and cognitive performance was assessed via various neurocognitive tests.

At the end of the four-year study, 601 participants had provided a hair sample and 123 of them had used marijuana.

These participants were compared to 123 adolescents who reported no cannabis use or had cannabinoids found in their hair.

Participants were matched on age, gender, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status to identify cannabis use as the key difference.

The researchers found that teens who used cannabis performed significantly worse on tasks measuring episodic memory – the ability to remember specific events from the past – and showed a small decline in word and sentence comprehension.

Furthermore, higher concentrations of THCCOOH in hair were linked to lower scores in both word and sentence comprehension and attention tasks.

Study author Natasha Wade, an assistant professor at the University of California San Diego, told PsyPost: ‘If we carefully determine cannabis use group status in teens aged 13-14 and match those with cannabis use to socio-demographically matched controls, we can see that there are group differences in memory, and that greater cannabis use was associated with poor verbal skills, inhibition, working memory and episodic memory.

‘Our analyzes were all cross-sectional, so a causal relationship cannot be inferred.

‘It is interesting to note, however, that when participants first entered the study at ages 9-10, there were no significant differences in cognitive performance between the groups.’

Cannabis is thought to affect the neuronal brain tissue related to memory.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, memory loss from marijuana use occurs because THC changes the way the hippocampus, a brain region responsible for memory formation, processes information.

As people age, they lose neurons from the hippocampus, which decreases their ability to learn new things. Exposure to THC could accelerate this loss of hippocampal neurons.

The research was published in the journal Addictive behavior.