How OJ’s defense team played the race card and won: Defense team weaponized Rodney King riots to help get him acquitted and honed in on racist cops at heart of investigation

Many African Americans remember the triumphant cheers when OJ Simpson’s historic not guilty verdict was read on October 3, 1995.

Because the case, as one commentator wrote at the time, was no longer about the slit throats of Nicole Brown Simpsons and Ronald Goldman.

It was about race.

And, it is argued, it was OJ Simpson’s ‘dream team’ of lawyers that made this possible.

Faced with overwhelming evidence pointing to the football star murdering his ex-wife and boyfriend, they have taken America and its history of institutional racism to task.

OJ Simpson’s “dream team” of lawyers realized that their best hope for an acquittal was to play on the racial tensions surrounding the case at the time.

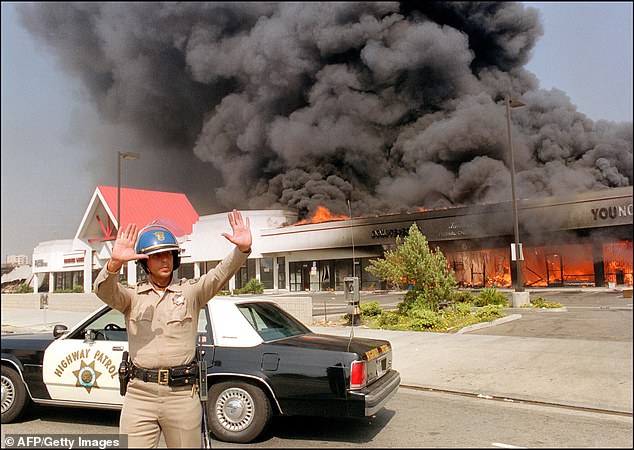

The trial came just a few years after widespread riots rocked LA following the brutal police beating of Rodney King, which exposed the police’s institutional racism.

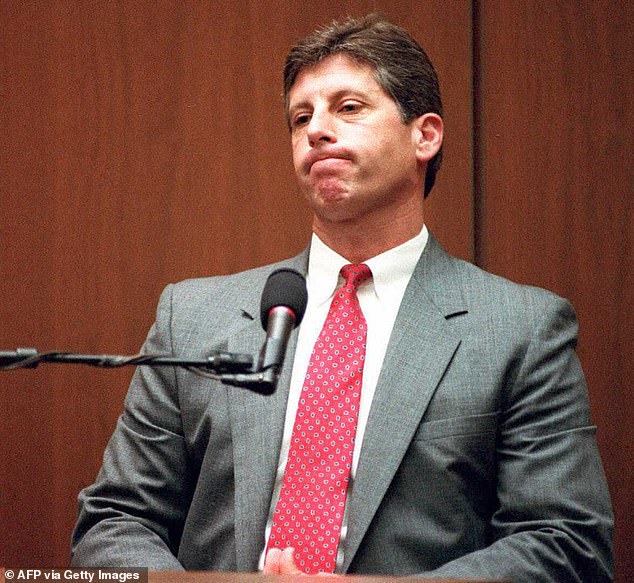

The defense also received a trump card when it emerged that Detective Mark Fuhrman, who handled key evidence in the case, had previously bragged about his racism.

The strategy was led by Johnnie Cochran, a longtime civil rights activist who was already something of a hero in the black community by the time he took on the case after litigating high-profile cases of police brutality.

Cochran’s tactic was to ask the jury not whether his client was a cold-blooded killer, but whether the Los Angeles Police Department had framed him as part of a racist plot.

This “should have been bizarre,” wrote Jim Newton, the LA times‘ chief reporter of the trial.

But the fact that it was potentially credible was a devastating indictment of the Los Angeles Police Department and its reputation.

The Simpson trial took place in the aftermath of the 1992 acquittal of police officers in the beating death of Rodney King in Los Angeles, which led to intense riots across the city.

They were also dealt a trump card during the case in the form of Mark Furhman, the detective who found the infamous blood-stained glove on Simpson’s estate, which matched a glove found at his ex-wife’s home.

A few months later, a series of tapes surfaced in which Furhman used the “N-word” 42 times and bragged about his racism to an aspiring screenwriter.

When he took the stand, he pleaded the Fifth when asked if he had ever made racist comments.

For the predominantly black jury it was as crucial a moment as the iconic showpiece ‘If the glove does not fit, you must acquit’.

“At that point, the Simpson trial turned into the Mark Fuhrman trial,” Dominick Dunne wrote Vanity fair in 1995.

But it wasn’t just the defense that knew race was a factor.

Cochran even criticized the prosecutor for adding Chris Darden, a black attorney, to their team to balance the skewed racial dynamic between prosecution and defense.

Tensions arose over strategy within the defense team, with Robert Shapiro (far right) maintaining the ‘race card’ and should not have been played by Johnnie Cochran (speakers centre).

Institutional racism was a fact of life for many African Americans in LA at the time

During the trial, African Americans were four times as likely to believe Simpson was innocent or framed by police, UCLA Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Darnell Hunt told the Associated Press.

Polls over the past decade show that most people still believe Simpson committed the murders, including most African Americans, but the racial and historical dynamics at play in the trial made it about more than just the murders.

Institutional racism was a fact of life for many African Americans in LA at the time, as it was for Cochran years before.

An illuminating story in the attorney’s autobiography, “A Lawyer’s Life,” describes how he is stopped by the LAPD while taking his young children to a toy store in his Rolls Royce.

The episode, which apparently stuck with Cochran, was dramatized in the drama series “The People v. OJ Simpson: An American Crime Story” in the episode “The Race Card.”

Viewers of the show would have had no doubt that it played a central role in the defense strategy, which features several real-life racial flashpoints throughout the trial.

One was the feud between Robert Shapiro, who was initially hired as Simpson’s lead attorney, and Cochran over strategy.

After the trial, Shapiro claimed he never agreed with the tactics.

“My position was always the same: that race would not be part of this case,” he said. ‘I was wrong. We not only played the race card, but dealt it from the bottom of the deck.”

He added, “Him [Cochran] believes that everything in America is related to race. I do not do.’

For his part, Cochran has insisted that this is an unfair portrayal of his strategy and that he hates the term “race card” because of the gross opportunism associated with it.

Adam B. Coleman, author of “Black Victim to Black Victor,” has a less favorable view.

“Simpson and his defense team exploited America’s racial wound, peeling off the fresh crust of the Rodney King debacle and inviting press vampires to endlessly feed our bleeding gash,” he wrote for The New York Post on Thursday.

“For months, the American media begged us to run a story about our inability to heal as a nation.

“Johnnie Cochran and others turned Simpson into a martyr for a racial cause he never cared about before.”