How good is YOUR GP practice? With five percent of Brits having to wait more than a MONTH to see their doctor, use our interactive tool to check how your practice scores in terms of number of patients per doctor, personal appointments and waiting times.

Calling your doctor’s office and making a same-day appointment may seem like the bare minimum requirement for a functioning healthcare system.

But waiting a month or more to see a doctor is becoming increasingly common, new analyzes show. One in twenty has to wait at least four weeks for a visit to the GP in England. In the worst affected parts of the country, including Gloucestershire and Derbyshire, the rate is closer to one in ten. In some areas, such as the Vale of York, four-week waiting times have increased by 80 percent in just one year.

Here, Mail+ has collected a host of NHS data to reveal how your GP fares in the nationwide battle to see a doctor.

The guide shows you how your GP practice scores across a range of appointment access metrics, including which practices are best for same-day appointments and how many other patients you are competing with to beat the queues. All data is correct as of November.

To make this comparison, we analyzed the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) GPs in the more than 6,000 practices in England and compared them with the number of registered patients.

By comparing the number of FTE GPs, you get a more accurate picture of the situation in your practice, given the number of doctors who currently work part-time.

Health chiefs say a GP-to-patient ratio of more than 1,800 could be unsafe as GPs risk rushing their appointments or becoming exhausted by the volume of patients.

This, in turn, can increase the risk that patients will miss the first signs of serious disease, with potentially devastating consequences.

Our analysis of GP data found that more than half (52 percent) of practices were above the 1,800 patient-to-physician threshold.

NHS data shows that access to same-day appointments varies hugely across the country.

For example, Chartwell Green Surgery in Southampton was the biggest offender, with 3.8 FTE GPs unable to make same-day appointments in November.

Medicus Select Care in Enfield, north London, also struggled, with just 2.9 percent of same-day appointments in November last year.

Patients who struggle to make appointments with a GP will be well versed in talking to practice receptionists in an attempt to book a place.

Our GP audit found that GPs outnumbered administrative staff, such as receptionists, by a rate of 20 to one at some practices.

Matrix Medical Practice in Chatham, Kent, employed almost 24 FTE administrative staff, compared to the GP’s one FTE.

High figures were also seen at JS Medical Practice in north central London (14 administrative staff for every FTE GP) and the East Lynne Medical Center in Clacton-on-Sea in Essex (12.8 administrative staff for every FTE GP).

Only 452 GP practices in England (7 per cent of the total) had a one-to-one ratio of administrative staff to GPs, or employed more doctors than receptionists.

We also measured what could be one of the most critical indicators of primary care practice performance: patient satisfaction.

In its annual survey, the NHS asked 759,000 primary care patients about their experiences with their GP between January and April last year.

A branch of Medicus Select Care in London’s Islington received the lowest overall rating in England, with just 11 percent of patients considering it ‘good’.

It was followed by Green Porch Medical Partnership in Sittingbourne, Kent (17 per cent), and Compass Medical Practice, a specialist primary care service treating people removed from other GP patient lists in the Lancashire region (19 per cent).

In total, only nine primary care services in England achieved a perfect score of 100 per cent.

While a total of 71 percent of patients rated their GP survey as good, this was the lowest percentage since the survey began in 2017 – when 85 percent rated their GP highly.

A decline in patient satisfaction is due to the fact that GP salaries continue to rise.

General practitioners, who typically work about three days a week, earn an average six-figure salary.

The struggle to access GP appointments is a complex issue, with doctors themselves reporting being overwhelmed by patient demand.

According to guidelines, GPs should not make more than 25 appointments per day to ensure ‘safe care’. But some doctors reportedly have to cram in almost 60 per workday.

Nationally, the doctor-patient ratio now also stands at one per 2,292 – almost a fifth more than in 2015.

The result is millions of patients being rushed through appointments, which critics have described as “goods on a factory conveyor belt.”

The struggle to access GP appointments in a timely manner is also having knock-on effects on other aspects of NHS care.

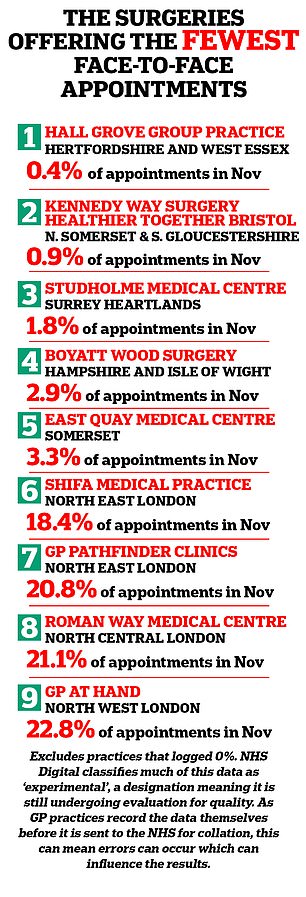

GP practices in England offer the fewest face-to-face appointments

GP practices in England, where 100% of appointments are face-to-face

The GP crisis is partly blamed on problems in emergency departments, as desperate patients seek help for problems they have not been able to resolve during a regular doctor’s appointment.

Despite the pressures facing primary care, ministers have quietly set aside a pledge to hire a further 6,000 GPs, a key part of Boris Johnson’s election-winning manifesto.

As of November last year, there were 27,483 fully qualified FTE GPs working in England.

Although this is an increase of 0.3 percent year on year, there are a total of 400 fewer general practitioners than in November 2021.

Analysts have said they believe England needs a further 7,400 GPs to close the gaps in primary care and allow patients to access it in a timely manner.

But the situation could get worse in the near future.

Many of the GPs currently working in the system are now retiring in their 50s, moving abroad or working in the private sector due to rising demand and NHS paperwork.

This exodus threatens to worsen the workload crisis, as remaining GPs have to take more and more appointments, creating the risk of burnout.

NHS Digital classifies much of the data used in our analysis as ‘experimental’, a designation that means it is still being assessed for quality.

In addition, because GP practices record much of the data themselves before sending it to the NHS for collection, this can mean errors occur that affect the results.