Hawaii’s fastest growing region is in ACTIVE lava zone where homebuyers can snap up bargains – but they must use cesspools for sewage and face having homes destroyed by volcano

House hunters are rushing to snap up real estate in an active lava zone that has become one of Hawaii’s hottest real estate markets.

In May 2018, Kilaeua volcano erupted, sending molten rock flowing through the coastal district of Puna.

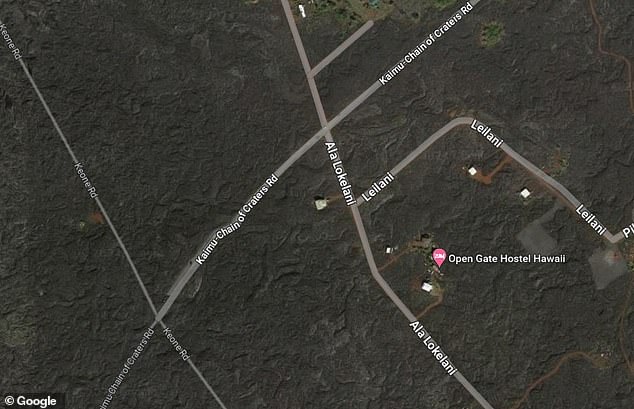

Lava engulfed the Leilani Estates subdivision, leaving thousands homeless. In the years since, newcomers have flocked to Puna because of the cheap housing prices.

The median home price on Oahu, often considered Hawaii’s most expensive island, was $729,000 last month, according to Redfin data. By comparison, homes in Puna can sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

Phoenix native David Booth and his partner were drawn to the region for one reason: affordability. The duo paid cash for a 1,500-square-foot home that was split into three units.

“You can’t get this at this price on any other island,” Booth told the Wall Street Journal.

Homebuyers have scrambled to snap up properties in Puna, a district in Hawaii with several active lava zones

In May 2018, Kilaeua volcano erupted, sending lava flowing through Lower Puna and displacing thousands of residents

During the eruption, twenty-four fissures opened, sending molten rock hundreds of feet into the air. Since then, many newcomers have come to the area in search of affordable housing

An eruption will occur at the summit of Kilauea volcano in Hawaii on June 7, 2023

During the 2018 eruption, 24 fissures opened in Lower Puna. The most famous is Fissure 8, now known as Ahu’aila’au, which opened near an intersection in Leilani Estates and shot lava 200 feet into the air.

It flowed to the sea, covering Leilani Estates and Kapoho and adding 875 hectares of new land to the island.

None of the 700 houses engulfed by lava have been rebuilt. Local authorities are prohibited from building affordable housing in lava flow hazard zones 1 and 2, where volcanic springs have repeatedly been active.

While many homeowners sold their properties to the county through a federally funded buyback program, that land remains untouched.

Puna has received a new fire station and a new police station in recent years, but the province is reluctant to invest further as its nearly 52,000 residents live under the threat of future eruptions.

There is no wastewater treatment plant or hospital. Many residents of the neighborhood filter their own rainwater and use cesspools to drain sewage.

However, this has not stopped newcomers from flocking to the region. Puna saw an influx of remote workers during the pandemic, causing a spike in housing demand.

Homes with repeat sales in Hawaiian Paradise Park, a Zone 3 subdivision, have seen a nearly 800 percent increase in value since 2000, according to data from the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization.

Puna has received a new fire station and a new police station in recent years, but the local government is reluctant to invest further due to the threat of future eruptions.

There is no wastewater treatment plant or hospital, and many residents rely on cesspools to get rid of sewage. Nevertheless, the district has seen an influx of newcomers since the pandemic, causing a spike in housing demand and driving up prices

Aerial photos show the region covered in igneous rock, remnants of the 2018 Kilaeua eruption

One property manager told the Wall Street Journal that she saw monthly rent for some three-bedroom homes skyrocket from $1,500 to $2,300 during the pandemic.

Longtime residents are struggling to keep up with rising rents, and local government is banned from building affordable housing in high-risk lava flow hazard zones 1 and 2

During the pandemic, prices in Puna skyrocketed. Liz Fusco, property manager at Hilo Bay Realty, said monthly rent for some three-bedroom homes has increased from $1,500 to $2,300.

And while these rates may seem cheap to newcomers, the surge in demand is having a devastating effect on locals.

Tina Garber, a cleaning lady who has lived in the area for more than 20 years, spends three-quarters of her monthly income on rent.

She lives in a 4,000-square-foot studio in the middle of a field of igneous rock.

Garber has been displaced twice in the past 18 months and will have to look for a new home again when her apartment comes up for sale in April.

“People who come here with money don’t realize it’s so hard to make it here,” Garber said.

“They think, ‘Oh, a good deal in Hawaii.’ But it causes a lot of pain and suffering to the local population.”