Has the world’s most mysterious text finally been cracked? Experts Claim 600-Year-Old Voynich Manuscript Holds Medieval SEX Secrets

The first confirmed owner of the Voynich manuscript was George Baresch, an alchemist from Prague who had mentioned in a letter that he had found it in his library “taking up his space.”

He learned that the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher had published a Coptic dictionary in Rome and claimed to have deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Baresch sent a sample copy of the script to Kircher and asked for clues to reveal what the mysterious manuscript meant.

It was purchased in 1912 by a Polish-American antique dealer named Wilfred Voynich (photo) (1865–1930), from which it takes its name

His 1639 letter to Kircher is the first confirmed mention of the manuscript found to date.

Kircher asked for the book, but Baresch would not hand it over because he considered owning it more important than knowing its true meaning.

After Baresch’s death, the manuscript passed to his friend Jan Marek Marci, who worked at Charles University in Prague.

A few years later, Kircher finally got his hands on the book when Marci sent it to him, as he had been a long-time friend and correspondent.

When John Mark sent it to Kircher, they found in the cover a letter written on August 19, 1665 or 1666.

It is said that the book once belonged to Emperor Rudolph II (1552-1612), who paid 600 gold ducats (about 4.5 pounds of gold) for it.

The letter was written in Latin and translated into English.

The litany of previous owners attempting to unravel its secrets continues as the manuscript becomes more entrenched in European folklore.

It is also thought that the manuscript was once in the possession of ‘Jacobj aTepen’, or Jakub Horcicky of Tepenec, a physician who lived from 1575-1622 and was widely known for his herbal medicine use.

No records of the book for the next 200 years have been found, but it was most likely stored in the library of the Collegio Romeo along with the rest of Kircher’s correspondence.

It probably remained there until the troops of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy conquered the city in 1870 and annexed the Papal States.

It was purchased in 1912 by a Polish-American antique dealer named Wilfred Voynich (1865–1930), from which it takes its name.

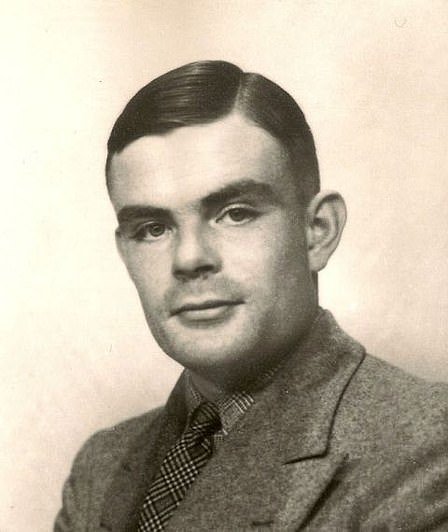

Alan Turing (pictured), the brilliant mind who led the campaign to crack the Enigma code at Bletchley Park during World War II, tried to understand the code but found it impenetrable

His acquisition of the manuscript is different from that of the previous owners, from whom it was passed from hand to hand.

According to folklore, during an acquisition trip he came across a suitcase containing the rare manuscript now known as the Voynich Manuscript.

He kept it in his possession until his death, and exhibited it to the public for the first time in 1915.

It has engraved itself further into folklore, and the mystery surrounding it deepened from this point on as the uncrackable code attracted the greatest minds for decades – all trying to discover its meaning.

Wilfred subsequently moved from Europe to New York and after his death the custodian of the manuscript became his wife Ethel Voynich (1864–1960).

After her death, the manuscript came into the hands of another dealer, Hans P. Kraus (1907–88), who eventually donated it to the Yale Library in 1969.

Alan Turing, the brilliant mind who led the campaign to crack the Enigma code at Bletchley Park during World War II, tried to understand it but found it impenetrable.

Theodore C Peterson, a priest, began the project of making a manual copy of the Voynich manuscript.

He completed it in 1944, and each page of the replica points out unusual features that could be important in deciphering it, such as strange strings of characters and common words.

He worked on the Voynich until his death and it helped a Danish botanist and zoologist, Theodore Holm of Catholic University, to tentatively identify 16 plant species in the Voynich.

William Friedman (1891-1969) is remembered as one of the world’s foremost cryptologists and became involved with the Voynich in the early 1920s while corresponding with his namesake.

During his work he developed the theory that the Voynich manuscript represented a text in a synthetic language (using or describing inflections).

It took research associate Dr Gerard Cheshire, pictured here, two weeks, using a combination of lateral thinking and ingenuity, to identify the language and writing system of the famously inscrutable document, he claimed.

John Tiltman was a British intelligence specialist who worked with William Friedman.

Friedman asked Tiltman for his opinion on the Voynich MS text and sent him copies of the final section.

He concluded that the text is far too complex to be the result of a simple cipher and to be the result of applying a standard cipher to plain text.

He spent some time discussing the option of a synthetic or ‘universal’ language, as proposed by Friedman.

The FBI also tried it during the Cold War, apparently thinking it was communist propaganda.

The US National Securities Agency collaborated with German codebreaker Erich Hüttenhain based on the earlier work of British codebreaker John Tiltman, as they felt it might contain communist propaganda.

Eventually a consensus emerged: that the manuscript was either impossible to solve or was written in gibberish, like an elaborate joke.

Dr. Gerard Cheshire, a researcher at the University of Bristol, claimed that it was written in a dead language – proto-Romance – and by studying symbols and their descriptions he then deciphered the meaning of the letters and words.